Sebastian Smee, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for the Boston Globe and formerly a reporter for The Art Newspaper, has written a spirited account of four friendships between titans of Modern painting—Manet and Degas, Matisse and Picasso, Pollock and De Kooning, Bacon and Freud—showing how an element of competitive tension stimulated the younger of each pair to surpass himself, sometimes in a single decisive breakthrough. The stories are familiar, but considered here together and recounted with exceptional sympathy and lucidity, they yield fresh insights.

The psychological and emotional dynamic underlying Smee’s idea of rivalry is summarised in the early pages of the book. This is not “the macho ideal of sworn enemies, bitter competitors… slugging it out for artistic and worldly supremacy. Instead, it is… about yielding, intimacy, and openness to influence. It is about susceptibility.” The historical moments in question—“usually three or four fraught years”—are those of maximum intensity when the artists were young and at their most radical, with only a handful of witnesses to their innovations, those being mostly their fellow artists, brothers-in-arms with whom they talked, drank and compared works. “If there is a fundamental difference between rivalry in the modern era and in earlier epochs,” Smee writes, it lies in a different conception of “greatness”, one based on the “urge to be radically, disruptively original”.

That the eight artists here are, unfashionably, all men is explained first by the argument that the heroic era of Modernism was still largely patriarchal and, second, by the author’s particular focus on a type of homosocial relationship, where solidarity is confounded with dogged individualism. Smee skilfully interweaves the personal—including the sexual and emotional—with the artistic and, however widely he circles, eventually closes in on his essential theme: a moment of revelation and a crucial breakthrough in painting. Each chapter is self-contained but certain common threads are discernible. For example, all four of his younger protagonists, Degas, Picasso, De Kooning and Freud, were consummate draughtsmen but, as painters, lacked the ease, freedom and spontaneity of their older friends.

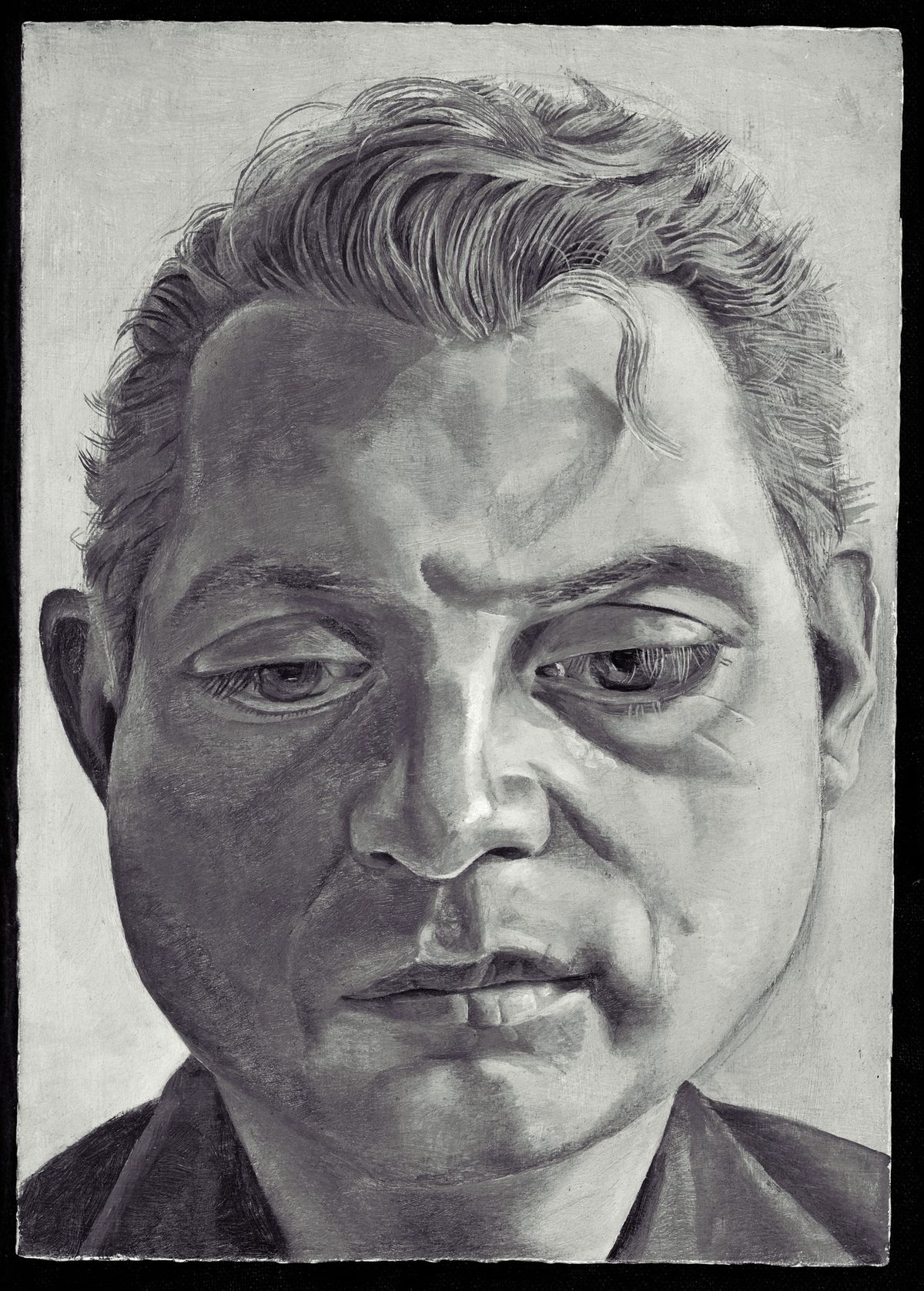

The book opens with Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. The author knew Freud well and has written and contributed to numerous books about him (most of the quotations here from Freud are from his own published interview). The two artists could hardly have been more different: Bacon, with his reckless, impulsive energy and embrace of chance, his suspicion of realism, disdain for illusion and horror of illustration; Freud in these early years fastidious and painstakingly exact in his thinly painted studies from life. The decisive moment came in 1954 when, after painting Hotel Bedroom, Freud stood up from his chair, his eyes aching: he never sat down to paint again. Under Bacon’s influence, he stopped drawing and his painting became more visceral, although he never relinquished his dependence on the model, whose presence excited him as much as it inhibited and distracted Bacon. A more profound change occurred in the art of Degas, who in the early 1860s abandoned history painting and allegorical subjects to become, like Manet, a painter of modern life, of “flux and instability”. Smee gives a vivid sense of the contrasting personalities of the two artists, of Manet’s insouciance in the face of controversy, and Degas’s aloof, brooding intelligence, his difficulties with women and complicated view of marriage. The leitmotif of this chapter is Degas’s painting of Manet and his wife, which Manet owned and at some point sliced vertically to remove her profile. We can only speculate as to the reason; perhaps Smee overdramatises the act by describing it as “slashing” in anger, when the missing section may have been calmly removed (with the approval of Mme Manet).

The delicate relationship between Picasso and Matisse in the period around 1907 is legendary, and Smee tells this fascinating story extremely well. He takes the reader step by step through Matisse’s evolution—he was 12 years older than Picasso and far in advance as a painter when they met in 1906—leading up to the day when Matisse showed Picasso an African sculpture he had just acquired. Ironically, when each artist later came to set eyes on the other’s barbaric masterpiece—Matisse’s Blue Nude and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon—neither was impressed.

Although the “battle” was only metaphorical in Paris, in New York’s Cedar Street Bar in the 1940s, painters really were beating each other up. The age of the artist as alcoholic he-man is thankfully past; yet while we may weary of tales of Jackson Pollock’s drunken misbehaviour, it is impossible not to marvel at his sublime flowering.

De Kooning’s jealousy leads to the one instance of “betrayal” in the book. Not only was he “number one”, as he put it, after Pollock’s death, but he began an affair with Pollock’s girlfriend (who survived the artist’s fatal car crash) within a year of the funeral.

These human dramas add spice to art history, and are often so enmeshed with creative developments as to be essential to our understanding. Exactly how we measure the impact of such relationships is the question: borrowings and quotations from the art of the past are easily detected, but the influence of contemporaries is harder to pin down. Ideas may be stolen, but this is not Smee’s point. His artists are not imitators; they are all supremely original. That does not mean they are self-sufficient, however, or immune from envy and resentment of others’ success, even when sharing their values.

• Roger Malbert is the head of Hayward Touring at the Southbank Centre, London, where he is responsible for a programme of contemporary art exhibitions, including the British Art Show and a series of artist-curated shows. He is the author of Drawing People: the Human Figure in Contemporary Art (2015)

The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals and Breakthroughs in Modern Art

Sebastian Smee

Profile Books, 420pp, £16.99 (hb)