This month, the Met Breuer opened Marsden Hartley's Maine (until 18 June), which looks at how the state became the "ur-subject" of the Modern artist's work. In this excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, the show's curators, Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch and Randall R. Griffey, outline how it shaped his vision and why he could never, despite his many travels, fully leave it behind.

“Marsden Hartley’s life made a full circle before its close,” wrote Elizabeth McCausland in the opening of her seminal 1952 monograph on the artist. This circle was inscribed around Maine: Hartley was born in the mill city of Lewiston in 1877 and died in the Down East coastal town of Ellsworth in 1943. At his request, his ashes were scattered over the state’s storied Androscoggin River, the waterway after which he had named a collection of poems published three years before his death. Hartley began his professional career in the first decade of the twentieth century by creating lush, dazzling landscapes of his home state’s western hills and concluded it by presenting himself (beginning in 1937) as “the painter from Maine” and producing roughly rendered paintings of—and publishing related poetry and prose about—Maine’s rugged landscape, coastal terrain, and working-class folk. In the interim, he made only brief visits to the state in 1916 and 1918, with summertime stays in 1917 and 1928. Nevertheless, he felt that Maine was with him both as a point of reference and as a concept throughout his many travels across Europe and North America. Yet Maine, the ur-subject that infused the full spectrum of his oeuvre, has been only selectively addressed by his earliest interpreters and subsequent scholars.

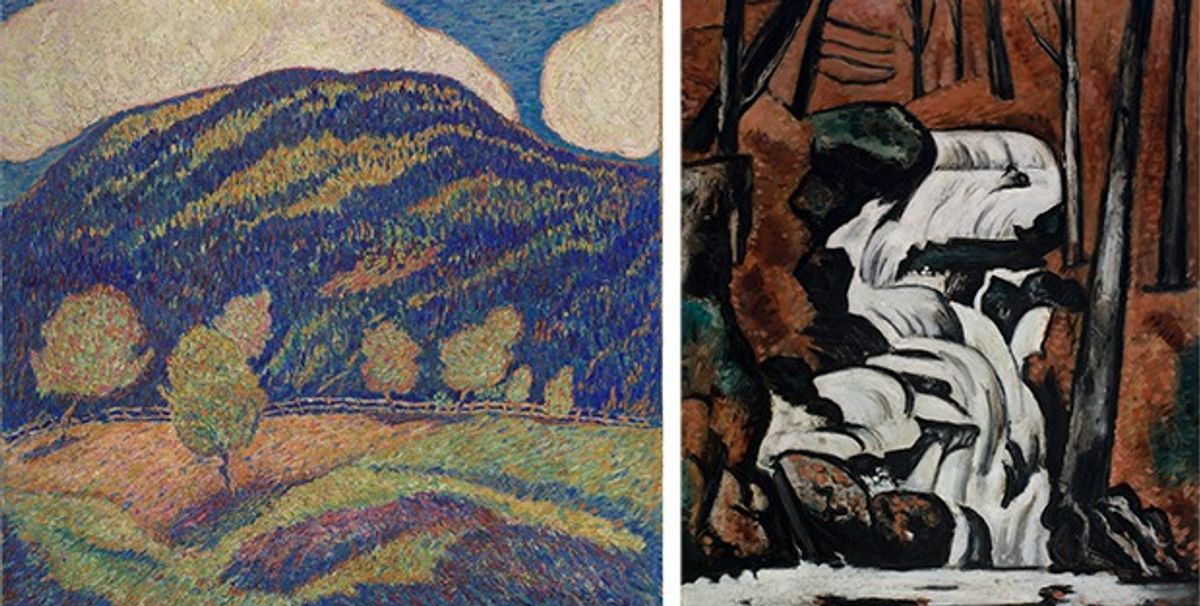

The exhibition Marsden Hartley’s Maine considers the artist’s complex, sometimes contradictory, relationship with his native state and how he navigated this relationship through painting. Hartley explored both what was exhilarating and what was desolate in Maine, finding there both light and darkness — the brilliant Post-Impressionist landscapes versus the bleak, deserted Maine works of his early career and the 1924 Paris Paysages; the bright, buoyant coastal views versus the mournful landscapes of his late career. It was this perception of Maine as a place of desolation, together with his habitual restlessness, that prevented him from settling there permanently.

Having endured a lonely childhood and stung by the devastating loss of his mother at the age of eight, Hartley sought to distance himself from the New England conservatism of his upbringing, outwardly rejecting his home state as a marker of heritage for many years. Writing from Bermuda in February 1917 to his dealer, photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz, he chafed at critic Henry McBride’s characterization of him as a Yankee in a review of Hartley’s Berlin paintings. “This Hartley . . . is a lean, intellectual, disillusioned type,” McBride wrote in the New York Sun: “‘Very American,’ as the Berlin newspapers said; so American that it is a fair guess that he is a Yankee.” To Stieglitz, Hartley retorted, “I come as near being a man of no land as anyone I know, spiritually speaking.” Earlier, in 1913, he had written to Gertrude Stein from Germany: “I am without prescribed culture,” adding, “I have grown up out of a strange thicket.” The contradiction in these statements — one a proclamation of self as tabula rasa and the other professing a far more complex and fraught relationship to his beginnings — suggests the fluctuating, unsettled nature of Hartley’s feelings toward his place of origin. The artist’s homosexuality — alluded to in his personal correspondence and conveyed in poignant, coded terms in some of his greatest works — may have contributed to an ingrained sense of isolation that could be only partially dispelled by chosen friendships and alliances.

Leaving Maine in 1893 to join his family in Cleveland, Ohio, Hartley began his art education in that city. He moved to New York in the fall of 1899 and spent the following summer in Maine, establishing a pattern of living and working between his home state and New York or Boston. In New York in April 1909, Hartley met Stieglitz, who would become not only his dealer but his confidante and counselor throughout much of his career. Stieglitz immediately recognized Hartley’s unique voice (“I believed in you & your work . . . I felt a spirit I liked”) and the very next month exhibited a selection of the Maine landscapes at his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, at 291 Fifth Avenue, known simply as 291. Hartley had another solo show at the gallery in the winter of 1912, and in April he left New York for his first trip to the modernist art capitals of Europe, Paris and Berlin. He returned briefly to New York in late 1913 to exhibit, again at 291, his earliest European works. Back in Germany by the spring of 1914, he remained there until wartime conditions forced him to return to the United States in the winter of 1915.

Hartley continued his travels on this side of the Atlantic, with stints in Provincetown (1916), Bermuda (1916-17), Ogunquit (1917), New Mexico (1918-19), and California (1919), before again settling in New York and playing a brief, rather nominal role in the international Dada movement. In late 1921 he returned to Europe, first to Paris and then to his beloved Germany, where he remained until 1923.

That year Hartley began a series of paintings that revisited his New Mexico landscapes before venturing on to Vienna and Italy. He traveled to New York in 1924 but quickly sailed back to Paris. The following year he moved to Vence, in south-eastern France. In 1926, 1927, and 1929 he painted in Aix-en-Provence, in an artistic communion with Paul Cézanne, an experience that bore fruit not only in his own paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire—a site immortalized by the French Post-Impressionist—but also, more subtly and more profoundly, in his later depictions of Maine’s Mount Katahdin.

The emotional toll of this peripatetic life began to weigh on Hartley, as he confided to Stieglitz in December 1924, and he began to “feel the need of finding an actual . . . spiritual pied à terre for the earthly as well as the idyllic side of my existence. . . . I want so earnestly a ‘place to be.’” External pressures also began to define his personal and professional relationship with his homeland. Chief among these was the belief, prevalent throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s, that the creation of great American art was predicated on an artist’s “rootedness” in his or her native culture. It was a trend in step with the rise of isolationist and anti-immigration sentiments during this period. Stieglitz was among the most devoted and active proselytizers of cultural nationalism through the promotion of his second circle of artists, including Hartley, Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, and John Marin, a group he christened in the 1925 exhibition “Seven Americans” and subsequently supported through his gallery An American Place, which opened in 1929. However, Hartley’s continued distance and perceived disconnectedness from the United States with his travels to Mexico, Germany, and Nova Scotia in the early 1930s contributed to a growing and eventually irreconcilable rift with Stieglitz, although his return to American subjects, and particularly to Maine, was due in large part to the influence of his former mentor.

But the narrative of a triumphant late-life return was only part of the story. Hartley transformed American modernism by approaching his place of origin as a lifelong creative resource. Fundamentally, the state offered the inspiration of nature as an alluring subject, as it had for many earlier American artists, including Fitz Henry Lane, Frederic Edwin Church, and, most famously, Winslow Homer, who created a vision that was unique among his contemporaries also painting in the state and whose precedent as a painter of Maine Hartley was acutely aware. Hartley’s early Maine landscapes of the western hills overlap and contrast with Homer’s coastal views, and his later work is in dialogue with that of other artists in Maine, both native-born and transplants, among them John Marin, Edward Hopper, painters in the Ogunquit and Monhegan art colonies, and those who produced the New Deal post office murals.

Hartley rendered Maine for reasons and with effects that extended far beyond topographical or physical description. The landscape served as a slate on which he pursued new ideas and theories pertaining to formal elements of color and design. It was a modernist testing ground. In his Maine landscapes of 1908-11, he experimented with abstracting from nature and established compositional devices that would recur throughout his oeuvre. Consider, for example, the many similarities connecting Carnival of Autumn (1908) and Mount Katahdin, Autumn, No. 2 (1939-40). Both present their respective landscape subjects in flattened, hieratic arrangements composed in tiers: lake and foothills, mountain — which appears well above the composition’s center point — and a band of blue sky filled with white clouds. Furthermore, the sublimity of the landscape suggested to Hartley the presence of a higher power, one that he was predisposed to understand through the lens of American Transcendentalism after he discovered Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Essays.

Maine’s dramatic change of seasons led Hartley to make landscapes in series, sustained meditations on the passage of time and the inherent tension between temporality and permanence. His paintings of the tempestuous coastlines are imbued with pain, loss, and alienation, themes that course through his life as they give power to his art. Maine’s lumberjacks and loggers appear in both the early and the late work. He also drew farmers and formidable New England spinsters early in his career, and to this collection of traditional types he added fishermen and hunters when he returned to Maine in his final years. Hartley’s protagonists are embodiments of the rugged terrain, stalwart expressions of a rough and precarious existence.

Hartley’s Maine includes absences and omissions. He painted the inland mountains and the coast as well as the people of these regions, but his Maine remains untouched by industrialization. Power lines and highways appear nowhere in his paintings. And while he grew up in the industrial city of Lewiston and even worked briefly in a shoe factory, these experiences are never invoked. When he did paint Lewiston, early in his career, it was the poetic Androscoggin River that figured in such works as River by Moonlight, a painting no longer extant but mentioned in an article from 1906. Later paintings of woodlots and log drives allude to the lumber industry, with dramatic views of nature touched by workers but no sign of the mills.

Hartley observed Maine as an outsider always returning, as a traveler remembering his birthplace. As the art historian Bruce Robertson has written, “The act of looking was [for Hartley] always mediated by memory.” He perceived Maine through the veil of the many places he had lived in or passed through — towns and cities in Europe and across North America; Hartley’s Maine was a global place. Other representations of the state, not only by other artists — Homer and Marin — but advertisements for tourists, film, and regionalist literature by, for example, Sarah Orne Jewett, all influenced the way the artist envisioned the land and its people. Hartley worked primarily from the imagination, in a studio, and less directly from nature. During winters in New York, he would rework and complete pictures begun in Maine during the summer and autumn. Distance, selectivity, imagination, and memory—these were the elements that shaped his vision.

Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch and Randall R. Griffey are the organisers of the exhibition

Marsden Hartley's Maine, Met Breuer, New York, until 18 June; the show travels to the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 8 July-12 November