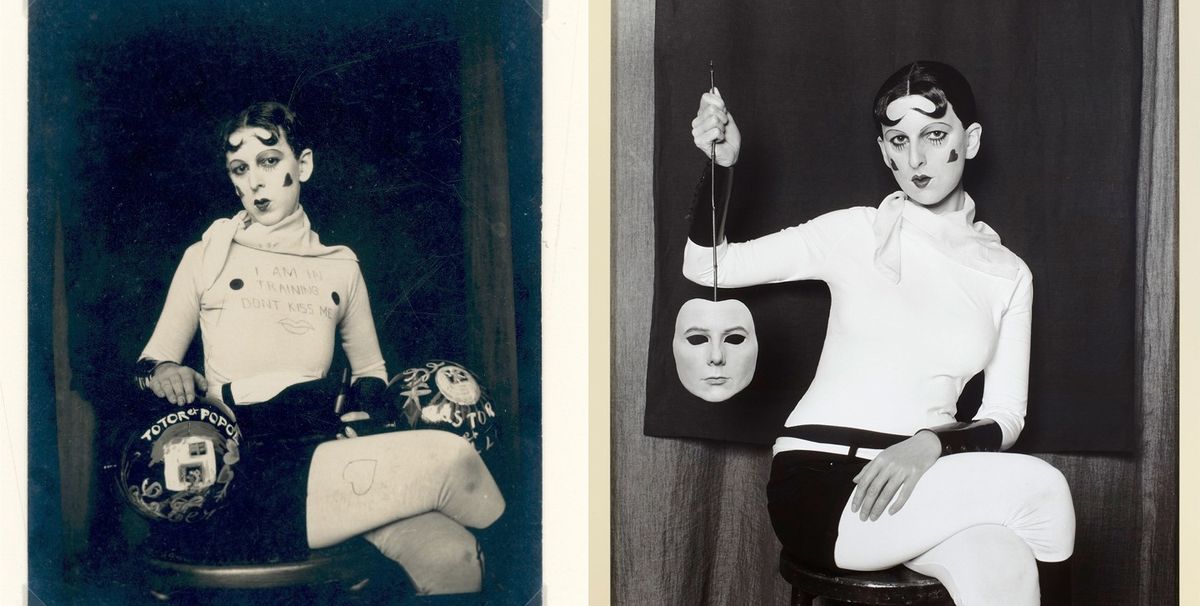

Behind the Mask, Another Mask: Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun, National Portrait Gallery (until 29 May)

Different times, places and circumstances separate Claude Cahun—the androgynous Surrealist who was imprisoned in Nazi-occupied Jersey for her role in the French Resistance—from the Goldsmiths-educated, Turner Prize-winning Gillian Wearing.

Cahun presented herself acting out countless roles in her small, mysterious and intimately uncanny photographs, which lay forgotten until the 1980s. In Wearing’s widely exhibited photographic self-portraits, on the other hand, the artist uses very evident albeit painstaking makeup and prosthetics to become younger or older reincarnations of herself, as well as to portray herself as others, whether family members or figures from art history—including Cahun herself.

But the pairing of the two is inspired. By bringing their work together we are able to compare how each artist uses the mask to reveal rather than to conceal. And how both harness the transformative power of masquerade to provoke and challenge conventional certainties about who and what we are.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32, Royal Academy of Arts (until 17 April)

A hugely ambitious and at times overwhelming visual ram-raid through the most tumultuous years of Russian history. Over the course of those 15 years, art was harnessed to politics in a way never equaled at any other time or in any other place.

Avant garde pioneers such as Kandinsky, Malevich, Rodchenko et al are not usually shown alongside the more traditional approaches to artmaking that were also prevalent at the time, whether more conventional academicism or the emerging Socialist Realism—or, as was often the case—a mixture of styles. But here, for the first time in the UK, arts of all kinds and in all idioms provide an extraordinary visual running commentary on this highly complex, constantly shifting and frequently contradictory political scene.

There are propaganda posters, constructivist teacups and photographs of man and machine. Alongside the multimedia plethora of worker heroes, there are many paintings of priests, domed churches and grizzled peasant grannies.

The range and variety of work is dizzying. In one gallery Vladimir Tatlin’s glider endlessly spins. In another there is a full-sized recreation of a modernist apartment designed by El Lissitzky in 1932, and Malevich’s last version of the Black Square painted in the same year.

But at the end of the show one exhibit stands as a bleak reminder of the human cost behind this explosion of images. The Room of Memory is a black box showing a looped slideshow of the official mugshots of just a tiny fraction of the millions who perished in the famines, the collectivisations and purges that also marked these 15 revolutionary years.

John Bock’s Hell’s Bells: a Western, Sadie Coles HQ (until 13 April)

You can always rely on John Bock to up the ante to the brink of breaking point and to squeeze a cliché until the pips squeak. He certainly doesn't disappoint in this rollicking feature-length movie which transforms the genre of the western into a gory, high-camp, gothic extravaganza.

Yet at the same time as he wheels out such tropes and stereotypes as the scary seer-monster-child, the put-upon good-time girl, the tortured priest and the gunslinger who just refuses to die, he consistently subverts them. He wrong-foots any easy predictability with unexpected moments of humour, pathos and lashings of excessive absurdity.

An extra layer of richness comes from the film’s intricate props and sets. These elaborate and often utterly repellent structures not only punctuate the action by appearing almost as characters in their own right, but have also evolved into arresting standalone sculptures. Presented in the gallery as a labyrinthine installation which has to be negotiated en route to viewing the film, they provide a prelude as well as a series of spin-offs and sub-plots to the main feature.

Simon Ling, Greengrassi (until 19 April)

Simon Ling is known for making richly executed paintings that depict his ordinary direct surroundings: corners of shabby buildings, details of inconsequential shop fronts, milk crates, children’s plastic toys or patches of waste land. These are often painted en plein air, with Ling considering the very act of perception itself, and all that this entails, as much the subject as the object or scene in front of him.

In the five recent paintings at Greengrassi it is a pile of logs in the yard outside Ling’s studio that is subjected to his very particular form of intense, emotionally engaged scrutiny. The longer you look at these stacks, the more you begin to notice how often quite subtle re-arrangements and shifts in viewpoint mean that recognisable forms recur, but in different guises.

Each log seems to loom out of the picture with a strangely animated presence, as if pulsating with an inner life. Chinks of deliberately revealed vivid orange underpainting further heighten the sense of an alternative but equally powerful reality sizzling beneath the thick layers of smothering paint. In this compelling new work, the subject may be banal, but the result is anything but.