In a small city in America’s dairyland, there is an overlooked arts centre that is a treasure trove of vernacular works of art. The John Michael Kohler Arts Centre (JMKAC) in Sheboygan, Wisconsin—a 100,000 sq. ft non-profit institution that includes 12 galleries, a theatre, studio classrooms and other communal spaces, along with a collection of over 20,000 works of art and artist-built environments—celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. But it remains a relatively unknown player in the broader art world, mirroring the position of many of the Outsider artists that it represents.

Named after the American industrialist John Michael Kohler, who founded the bathroom and kitchen fixture company, the centre’s current home was completed in 1999 under the former director Ruth DeYoung Kohler, the magnate’s granddaughter and heiress to the family fortune. She is credited with having built the institution’s behemoth collection of vernacular and folk art, often with the aim of acquiring an artist’s entire oeuvre in bulk. Ruth Kohler emphasised “the importance of keeping works together and showing artist-built environments as they were—or as close as possible to how they were”, says Karen Patterson, the centre’s curator.

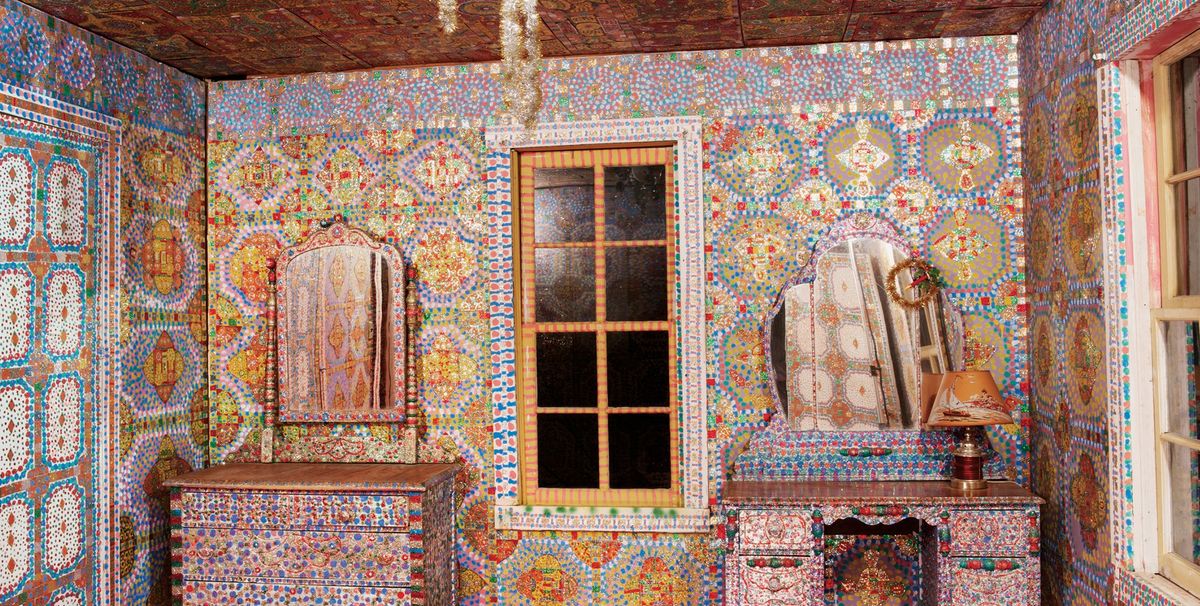

The Kohler Foundation made its first major acquisition in 1983, when it bought more than 600 works by the late Milwaukee-based Outsider artist Eugene Von Bruenchenhein—shortly after the artist died, and decades before his name or the genre became popular. Kohler also worked with Von Bruenchenhein’s widow to document and conserve their deteriorating home and his body of work. The self-taught artist’s psychedelic paintings, poems, erotic photographs of his wife and sculptures made from chicken bones are now preserved, along with works by artists such as Mary Nohl, David Butler and Carl Peterson, in the centre’s 6,000 sq. ft basement, just one of the storage spaces filled with work that the foundation owns, totalling over 46,000 sq. ft.

To commemorate its anniversary, the centre is hosting a yearlong series exhibitions titled The Road Less Traveled featuring 15 “environments” created by contemporary self-taught artists, with responses and analysis by scholars, curators, musicians and other visual artists. Among the first round of installations is an assembly of 100 sculptures by the Indian artist Nek Chand (1924-2015), known for building the Rock Garden of Chandigarh, a 40-acre site inhabited by more than 10,000 rock sculptures. The architect and University of Liverpool professor Iain Jackson spent several months working alongside Chand to catalogue every piece in the garden, and published his PhD thesis on Chand’s practice. One of the four catalogues that Jackson published is on view at the gallery.

The centre also runs an artist-in-residency programme that brings international artists to work for two to six month in studios with 24-hours access to the pottery or foundry departments at Kohler’s main factory. The Arts/Industry programme has supported over 500 artists since it was founded in 1974 and each year it accepts 16 residents from a pool of around 400 applicants. Among the artists currently on-site is the Los Angeles-based sculptor Joel Otterson, who returns to the programme after having first participated in 1991. He is developing a series of decorative concrete objects that “reinvent the American home”, the artist says, adding that the industrial environment sets the residency apart from others. “It’s wild to drive a forklift around the factory and realise that this is my studio.”

Last autumn, Kohler stepped down as director after more than 40 years to focus on developing the Arts Preserve, a 39-acre indoor/outdoor space on formerly city-owned land near the arts centre that will house and conserve artist-built environments. The project is slated for completion in 2020. The foundation has also helped preserve sites in their original locations elsewhere in Wisconsin, like the James Tellen Woodland Sculpture Garden in the nearby town of Wilson, and across the country, like Samuel P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kansas.

The centre’s new director Sam Gappmayer plans to introduce initiatives that will make the museum “a more active participant in national and international conversations about vernacular art”, he says. Although Gappmayer’s background has largely been in reviving financially failing institutions, he says that is certainly not the case with the Kohler Arts Center, which has a $25m endowment and is supported, in part, through contributions from the Kohler Trust for the Arts and Education. While the museum receives around 100,000 visitors each year—an impressive figure considering the city has less than 50,000 residents—Gappmayer wants to reach a broader audience and raise the museum’s profile as the “premier centre for the study and appreciation of vernacular art—a hidden gem in the Midwest”.