A packet of Wrigley’s spearmint gum floats, somewhat surreally, in front of a spare, geometric vision of Manhattan. A cartoonish car swerves, minutes from impact, in front of a careering red lorry on an overcast, curving, country road. The Brooklyn Bridge, its cables and wires snapped, appears to be on the point of melting: a doll-like woman sits and watches, apparently unaware of the missile sticking out of her back. For Europeans, the 1930s was the time of the last great surge of creativity in Paris and the glittering decadence of Berlin before the continent slid into the darkness of war, the Holocaust and violent totalitarianisms. America after the Fall: Painting in the 1930s at the Royal Academy in London, organised by Judith Barter of the Art Institute of Chicago, reminds us that times were tough in America too. So tough, in fact, that even artists were given funding through President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programmes—a fact that had a profound impact on American art in the 1930s.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a decade of the Great Depression. In the Plains states, crop failures and the Dust Bowl forced migrations as Jim Crow laws, instituted in the period of Reconstruction following the Civil War, persecuted millions African-Americans in the South. At the same time, fears that the rising tide of fascism in Europe would reach American shores inflected much of the art of the period. This is an exhibition full of anxiety, of joie de vivre in the face of disaster and of the emptiness of capitalism’s broken promises. And, Barter seems to argue, of competing visions for the future of American art—and the nation.

America after the Fall was first presented at the Art Institute of Chicago, home to the most famous work in the show, Grant Wood’s creepy American Gothic (1930). This is the first time the weird Hans-Memling-meets-primitivism painting of a conservative farming couple has left the US since it was painted (it first travelled to Paris and now London). The exhibition has been reconfigured in each city, but the central theme is the same: what happened to art and society after the crash and “fall” of the title. Barter says she has been asked many times about the show’s apparent relevance to Donald Trump-era America, but of course the show was planned long before the November 2016 election. The better parallel is between 1929 and the banking crisis of 2008, the enormous impact of which—Trump, Brexit, rising nationalism, protectionism and populism worldwide—are only now becoming apparent.

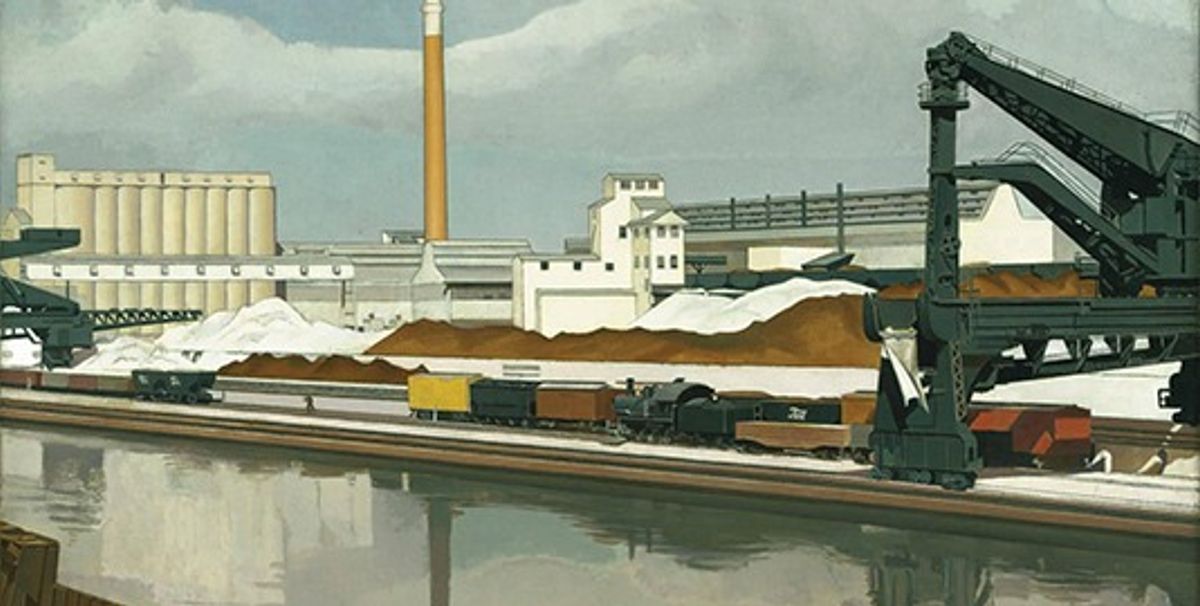

It’s a big subject to pack into a show of just 45 works by 32 artists but, unlike the Royal Academy’s sprawling and patchy Abstract Expressionism show last year (now at the Guggenheim Bilbao, until 4 June), it is tightly constructed. Barter is a master of point and counterpoint: Charles Sheeler’s cool, almost photorealist celebrations of growing American industrial power are set beside Charles Demuth’s restrained 1931 depiction of a derelict factory in his home town of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Sheeler, a well-known photographer who collaborated with Alfred Steiglitz and Paul Strand, was commissioned to make work by the likes of Henry Ford and the business magazine Fortune, which was founded by Henry Luce in 1930, partly in an effort to restore the image of American business after the crash. The implication is that Sheeler had confidence, even amid the Depression, that industry was the future. Demuth was clearly less certain. He called his picture of industrial abandonment And the Home of the Brave, which he painted in 1931, the year the Star Spangled Banner had become the US national anthem. These ironies and contradictions run throughout the exhibition.

Aaron Douglas, a black American artist who became a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance, painted a picture titled Aspiration (1936) of three African Americans standing on the shoulders—and the labour—of their slave forbears. Filled with hopes of equality and the potential that America’s emerging cities might offer, the trio are now armed with tools of education and look up to a great hill above, on which stands an ultra-modern factory and what appear to be the skyscrapers of New York. But in another room is the white working class painter Joe Jones's bitter picture American Justice (1933), which depicts the body of a young, lynched black woman lying on the ground. Behind her, eight Klansman stand chatting by a burning building—presumably her home. (Barter says incidences of lynching rose dramatically in the years immediately following the crash). Jones, like some of the other painters in this show, was an enthusiastic member of the Communist party, at least at this point in his career, and took its exhortations seriously to paint works documenting social injustice.

In London, the exhibition starts with a new opening section, designed to remind us that, just before the crash, vibrant New York was seen as the city of the future. Charles Green Shaw’s work titled Wrigley’s (1937) is an unashamedly optimistic painting of a pack of chewing gum set against the New York skyline. Shaw proposed it, unsuccessfully, as a possible advertising poster to the manufacturer, but it demonstrates both his enthusiasm for European Modernism (he had just seen the Museum of Modern Art’s 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism) and his interest in finding an American art language. It is an upbeat picture that celebrates American consumer culture, prefiguring the Pop art of Warhol and Lichtenstein by more than two decades. Equally, it is hard not to enjoy the rhythmic vibrancy of Stuart Davis’s New York-Paris No. 3 (1931). As the title suggests, Davis was bridging a gap between 15 months spent studying art in France and his return to New York. It owes a clear debt to Fernand Léger, but like Shaw, Davis was also developing his own, American artistic language.

The 1930s was a decade of mass migration from America’s rural interior to the rapidly growing cities of the east and west coasts. Artists were unsurprisingly inspired by this rapid change—especially as the New Deal programmes favoured painting of American scenes. These were deemed particularly appropriate for schools, post-offices and other government buildings. But artists took very different approaches. The Regionalists, much better known in the US than in London, included artists such as Grant Wood, John Stewart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton (who was a teacher of Jackson Pollock). Their rural, bucolic paintings harked back to a pioneer, settler, small-town farmer past and the implication—so popular with the conservative right in Europe and America even today—is that the past was “a better place”. Other artists, like Reginald Marsh, paint the urban streets as a vital, sexually exciting melting pot. In Twenty Cent Movie (1936) he celebrates the escapism and excitement of the movies. Smartly dressed women mingle with streetwalkers, stage door johnnies, spivs and shysters outside a movie theatre advertising titles including “the Joys of the Flesh” and “Stripped Bare.”

Some of the strongest pictures in the exhibition are the ones that hint at the terrible anxieties of the decade. Edward Hopper, whose work can look sentimental, benefits from the context of this exhibition. New York Movie (1939) and Gas Station (1940) hint at the quiet loneliness of many Americans lives. Wood, whose best work is less nostalgic, depicted the moment before a crash as a huge red truck that careers towards automobiles in a work titled Death on the Ridge Road (1935). We watch, powerless to intervene—a metaphor, perhaps, for the stock market collapse. Telegraph poles loom like abandoned crosses, or primitive grave markers. An early—indeed unrecognisable—tondo by Philip Guston, Bombardment (1937), is his powerful response to the horror of Guernica: by now America was pondering the war that would soon engulf it and Europe. At the centre of the painting is a violent explosion around which bodies fly; a dying baby grips its mother in a cruel parody of the Madonna and child; and on the right, a gas-masked figure hangs on, futilely, to a rubber breathing tube.

The exhibition finishes with a section devoted to the artists who prefigure Abstract Expressionism, with an early, semi-figurative work by a 26-year-old Pollock taking a central position. The degree of debt at this point to European Modernism is unavoidable. Pollock’s Untitled (1938-41), a mix of swirls and angles with the half-glimpsed heads of men and beasts, shows the impact of his encounter—which Barter calls "life changing"—with Picasso’s Guernica (1937), which travelled to New York in 1939. Such influence ran deep in America. Arthur Dove's abstract pictures of American jazz owe much to Wassily Kandinsky, while Ilya Bolotowsky’s Study for the Hall of Medical Sciences Mural at the 1938 World’s Fair in New York bears more than a passing resemblance to the work of Juan Miró.

This exhibition shines a fascinating light on a turbulent era in America’s history, both political and artistic. There are social radicals and social conservatives, Communists and the non-aligned. There are artists heavily influenced by European Modernism and those who turned against it. There are artists reviving folk art and artists inspired by Social Realism, Surrealism, contemporary magazines and cartoons. Judith Barter suggests that the New Deal meant that “for the first and only time” artists were not dependent on the market, allowing for stylistic experimentation and the chance to make work inspired by social crises.

In 1939, the left was dismayed that Josef Stalin signed the Non-Aggression Pact with Adolph Hitler just as Social Realism as a style was becoming corrupted by Soviet and Nazi artists alike. American artists increasingly chaffed at the perception that the New Deal meant they had to paint conservative American scenes. Worse, early incarnations of the House Un-American Activities Committee included investigations into Communist and socialist visual artists, as well as the now-better known Hollywood purges, and many artists, Barter suggests, lost heart. The stage was set: by 1949, American abstract painting would take a central place on the international art world stage and Pollock would be dubbed by Time magazine “America’s greatest living artist”. Seventy years on it is a delight, however, to be presented with a much more nuanced and complex picture.

Jane Morris is editor-at-large at The Art Newspaper

America after the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 18 September