ITALIAN RENAISSANCE DRAWINGS

The finest Italian Renaissance drawings belong to its three 15th- to 16th-century giants—Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. “Drawing was indispensable to the art of this time, and just as humankind became the centre of everything,” says Julian Brooks, the senior curator and head of drawings at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, one of the world’s most acquisitive museums, including in this area. Driving the genre, Brooks notes, was the greater availability of paper by the late 15th century.

When studies by the big three come to market, “the sky’s the limit”, says Gregory Rubinstein, Sotheby’s worldwide head of Old Master drawings. Indeed, when Raphael’s Head of a Young Apostle (around 1519-20) was offered by Sotheby’s out of the Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth in 2012, there was a 17-minute bidding war before the drawing sold for £26.5m (£29.7m with premium), making it the priciest work of art to sell at a London auction that year. In December, the Paris auction house Tajan announced to great excitement the discovery of a double-sided drawing by Leonardo, valued at €15m.

As in most niche Old Masters categories, high quality is in short supply but, outside of the big three names, there are other fine 16th-century Italian works that excite. In December, a rediscovered black-and-red chalk portrait by the Florentine Andrea del Sarto sold for €3.2m (est. €500,000-€600,000) at the regional auction house Gestas Carrère in Pau, France. Brooks admits to having a “soft spot” for Del Sarto too; he recently co-organised a major dedicated loan exhibition at the Getty.

DUTCH GOLDEN AGE PAINTINGS

Perhaps one of the most surprising boosts for Dutch Golden Age (17th-century) painting has been its appeal to art enthusiasts and buyers in Asia. With this in mind, highlights from Masterpieces from the Leiden Collection: the Age of Rembrandt (until 22 May), the current exhibition at the Louvre, Paris, will travel next to the Long Museum in Shanghai, then to the National Museum in Beijing. The collection, built since 2003 by the metals investor Thomas Kaplan and his wife, is particularly strong in works by Rembrandt and also includes Johannes Vermeer, Jan Steen and Gerrit Dou. The London dealer Johnny van Haeften—who is helping to support the exhibition—says that this will be the first time that work by Vermeer has been shown in Beijing.

According to Van Haeften, today’s biggest collector of Dutch Golden Age paintings lives in Hong Kong. Identifying similarities between the Asian and Dutch aesthetics, he says: “Blue and white porcelain is shared and there is [also a shared] a sense of calm, peacefulness and wellbeing.” Plus, there are historical ties that can be traced back to the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century.

At the recent Old Masters auctions, as well as at Tefaf Maastricht last year, some of the most notable sales were of Dutch Golden Age works. This market is still one of steady rather than spectacular growth, however, and a lesser work by a great name tends to be a collecting error. “Better to buy a good work by a minor master such as Pieter de Molijn than a rotten Van Goyen,” Van Haeften says.

MAPS

Maps have taken on new meaning in the 21st century, explains the rare maps and books dealer Daniel Crouch. “We encounter them all the time now. People travel and emigrate more than before—whenever you Google a restaurant on your phone, a map comes up.”

This has broadened the appeal of the niche category for older maps, which came on to the high-end collecting radar only in the mid-2000s. For example, specialists say that maps now attract more female buyers, rather than tending to be an almost exclusively male preserve.

One advantage of being a map-seller is that there is nearly always something to offer buyers from whichever part of the world happens to be economically prosperous. Crouch is selling more maps of ancient China these days, he says, but not many showing Italy or Greece.

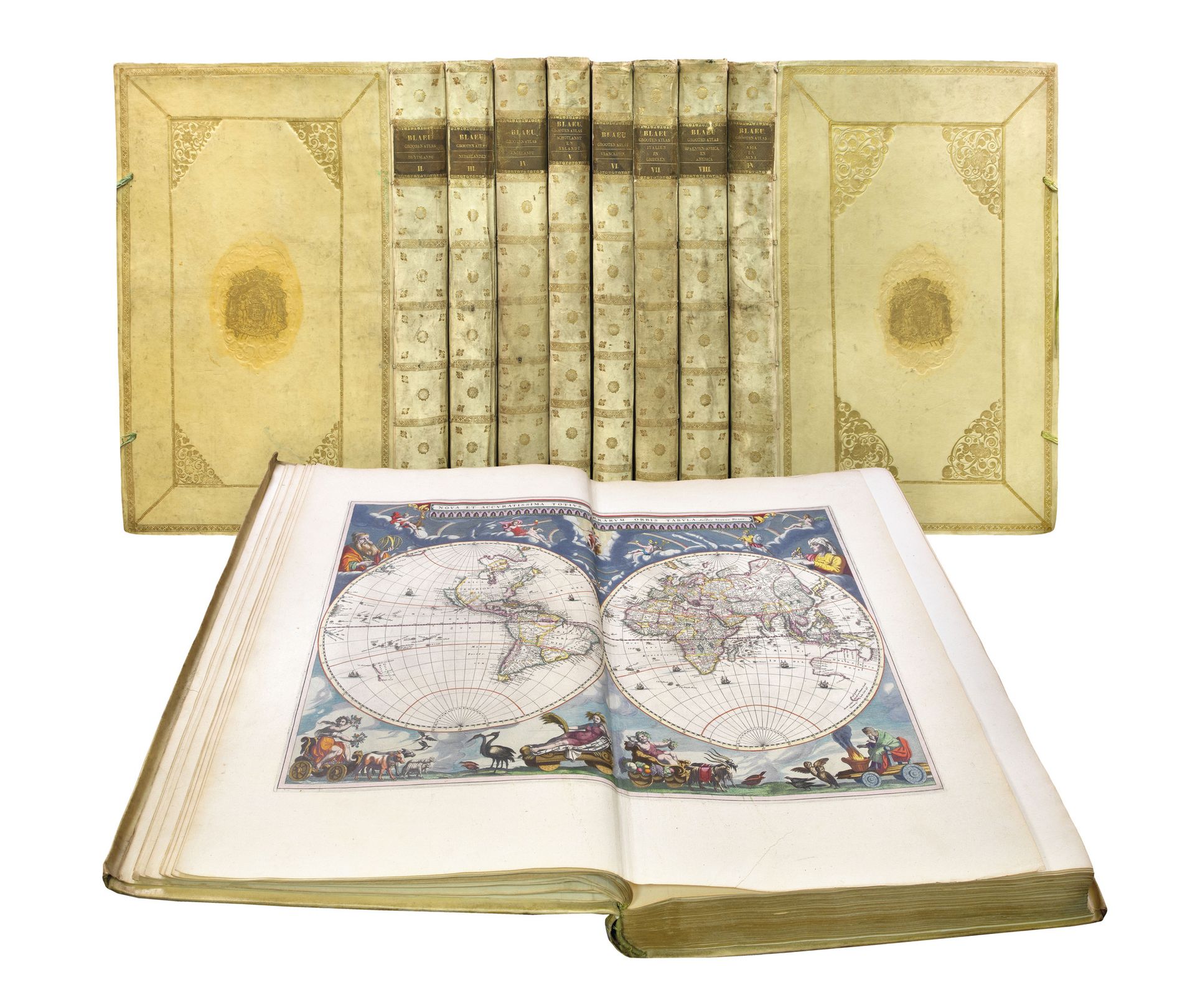

Complete atlases are much prized, particularly those by Willem Blaeu (1571-1638) and his son Johannes (1596-1673), the official hydrographers of the Dutch East India Company. Crouch is bringing a nine-volume version of their Atlas Maior to Tefaf Maastricht this month (1662-65; £650,000).

Maps are also increasingly seen as beautiful items in their own right, akin to pieces of visual art; indeed, the banner on the homepage of Tefaf’s website is a map. Those made to be standalone are currently in vogue, partly because their generally larger size can fill a wall (priced on average up to £200,000). “There has been a huge effort in presenting maps as objects of desire,” says Matthew Haley, the head of Bonhams’ books department.

CONTEMPORARY JEWELLERY

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2013 exhibition Jewels by JAR—the name by which the contemporary jewellery designer Joel A. Rosenthal is known—helped position the field within the realms of fine art. One item among the 400-plus in the New York show, a gold, diamond and green garnet Parrot Tulip bangle, sold for SFr3.5m against a SFr190,000 to SFr290,000 estimate at Christie’s in 2014.

JAR is one of only a handful of niche contemporary designers—others include Wallace Chan in Hong Kong, Viren Bhagat in India and the European specialists Hemmerle—to have broken into the international field previously dominated by bigger businesses such as Boucheron, Cartier and Bulgari.

“People will now travel across the world to visit the one shop in the one city,” says François Curiel, the chairman of Christie’s Asia Pacific. The auction house now has shops (“salons”) of its own in New York and London.

Christian Hemmerle, who runs his family firm with his wife Yasmin, says that buyers look for “the unusual, the individual and craftsmanship, in a world where those are rare”. At Tefaf Maastricht, he will have pieces combining diamonds with pebbles.

Considerable demand has been coming out of Asia recently. Curiel says that 31% of Christie’s jewellery sales go to the continent. Terry Chu, the head of jewellery for Phillips Asia, sees as many buyers from Taiwan, Indonesia and Hong Kong as from mainland China. Up-and-coming designers from Asia such as Cindy Chao are attracting buyers in the US, where the actresses Salma Hayek and Sarah Jessica Parker are fans.

EARLY PHOTOGRAPHY

Early photography (1830s-60s) emerged relatively late as a collecting category, boosted by a UK auction of Julia Margaret Cameron’s Herschel Album (1864-67) in 1974. This grouping of 94 portraits of Cameron’s famous British contemporaries sold to a US collector for £52,000, then a world record price for photography. The album was saved for the nation after being refused a UK export licence.

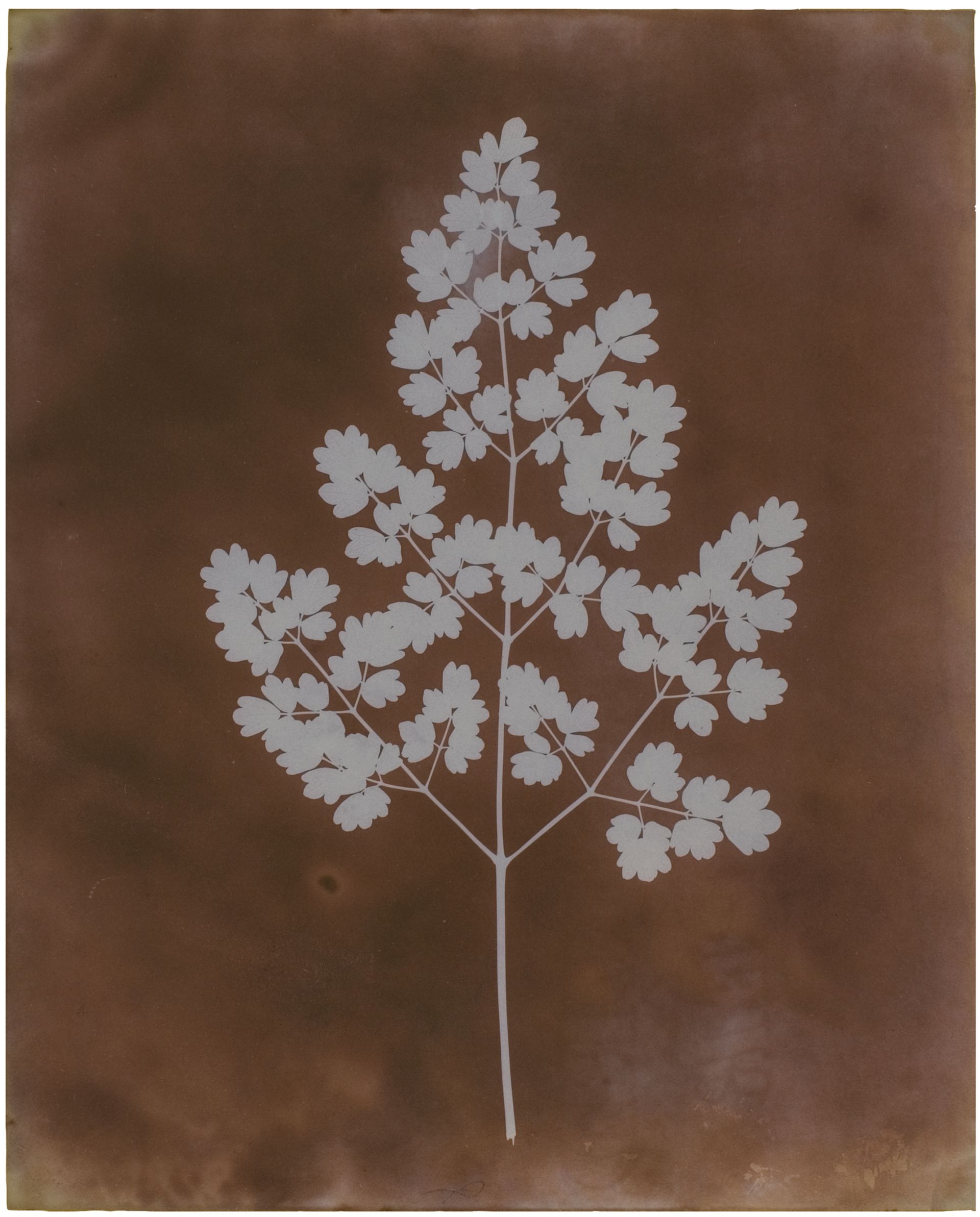

One of the fascinations of early photography is the extensive process behind what today can be achieved with a quick press of a mobile-phone screen. William Henry Fox Talbot was known as the “father of photography”, and his earliest works are popular with collectors. These “photograms” captured the effects of sunlight on photographic paper but without using a camera—a process that still attracts photographers today. The New York dealer Hans Kraus is dedicating his booth at this month’s ADAA show in New York (1-5 March) to Fox Talbot’s photograms, alongside works by the contemporary photographers Hiroshi Sugimoto and Adam Fuss that use the same technique. Fox Talbot “continually evolved experimentation”, says Greg Hobson, the curator of photographs at the UK’s National Media Museum and the co-curator of its recent dedicated exhibition.

Early Fox Talbots can hit the $500,000 mark, while his later works sell for between $50,000 and $150,000, provided they have survived in decent condition. That is not a given: photographic paper is “monumentally fragile”, says Matthew Haley at Bonhams.

Cameron’s work is also still sought after and in greater supply (the photographer was prolific and an astute businesswoman); pieces can be picked up for under $10,000.

MEDIEVAL SCULPTURE

The specialist dealer Sam Fogg says that demand for and tastes in Medieval sculpture are shifting away from 12th- and 13th-century ivory and enamel pieces from Paris towards later, polychrome wood items from Spain and Germany.

Fogg identifies several reasons for the shift. The uncertainties around possible bans in the ivory trade have “quietened the market”, he says, while German 14th- and 15th-century pieces—popular under the Nazi regime—are only just coming back into fashion. Also, Spain’s Medieval sculptors were prolific, solving the perennial problem of dwindling supply in the Old Masters market.

Named artists are rare in this field—and not necessarily the best. “Names are a bit of a red herring. Some of the finest things we’ve had have been anonymous,” Fogg says. And while condition is important, over-restoration is more of a concern.

Unlike most other collecting categories, Medieval sculpture, with its religious subject matter, is not attracting significant interest from Asian art enthusiasts, and Europe and the US are still the main sources of demand. But it has had a boost from buyers who like contemporary art—including living artists. Jeff Koons is a collector of Medieval German sculpture— in 2008 he paid $6.3m for an early 15th-century limewood St Catherine by Tilman Riemenschneider at Sotheby’s. The British artist Cecily Brown has also drawn attention to Medieval Madonna and Child sculptures in a video for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.