Auction houses, reckoning with weak sale totals in 2016 and facing continued uncertainty in 2017, are beefing up their private sales services, seeing it not only as a way to pad the bottom line in lean times but also as an increasingly necessary tool in their business-getting arsenal.

Sotheby’s announced in February that it had hired David Schrader, a managing director at JPMorgan Chase, as head of private sales for contemporary art. In a statement, Amy Cappellazzo, chair of Sotheby’s Fine Art Division, called Schrader a “seasoned market player” and praised his acumen as a collector himself.

Meanwhile, at Phillips, several key hires—from Cheyenne Westphal, the former worldwide head of contemporary art for Sotheby’s known for her deals, who begins as chair this month, to Vivian Pfeiffer, the former director of private sales for Christie’s Americas, now the head of business development at Phillips—signal a new focus on private transactions.

Private sales by individuals and galleries have long made up an invisible iceberg in the market, but according to the latest Tefaf art market report, by Rachel Pownall, they rose in 2016 to account for around 70% of all art sales worldwide.

Meanwhile, auction totals have fallen. According to a recent report by London-based research firm ArtTactic, totals for sales of post-war and contemporary art in New York and London were $2.3bn in 2016, down 32.7% from 2015. Some of the loss can be attributed to lot volume, which fell by 17.5% in the fourth quarter compared with 2015. The pinch is felt most acutely at the highest end of the market. According to the same report, the number of $20m-plus lots sold in contemporary evening sales was down 55.2% compared with the previous year.

Whether those bigger-ticket works stayed on their owners’ walls or found another outlet in the marketplace is an open question. Bloomberg’s Katya Kazakina reported in February that one of the biggest art deals of 2016 was the $150m private sale of Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912). (Owner Oprah Winfrey reportedly agreed to sell it after she was approached by the dealer Larry Gagosian, who had a buyer in China on the hook.)

Auctioneers increasingly view their private sales divisions as a way to capture commission on property that is not bound for the block. At Christie's, such transactions—which may include works of art brokered by the house from client to client, or those offered in selling exhibitions—totaled $935.5m in 2016, an increase of 25% from 2015, and accounted for 16.2% of the year's $5.4b total. At Sotheby's, private sales were down 13%, to $583m, or about 12% of consolidated sales.

The chief benefit of selling privately—discretion—knows no season. But facing market uncertainty, and with the houses scaling back on guarantees, it makes sense from the seller’s side to seek out alternatives. “People don’t know the price, there’s no risk of a public failure. In a market that is less predictable, with sales volumes falling and numerous events taking place that make people worried, the private sale route is more secure and more controllable”, says Ed Dolman, the chief executive of Phillips.

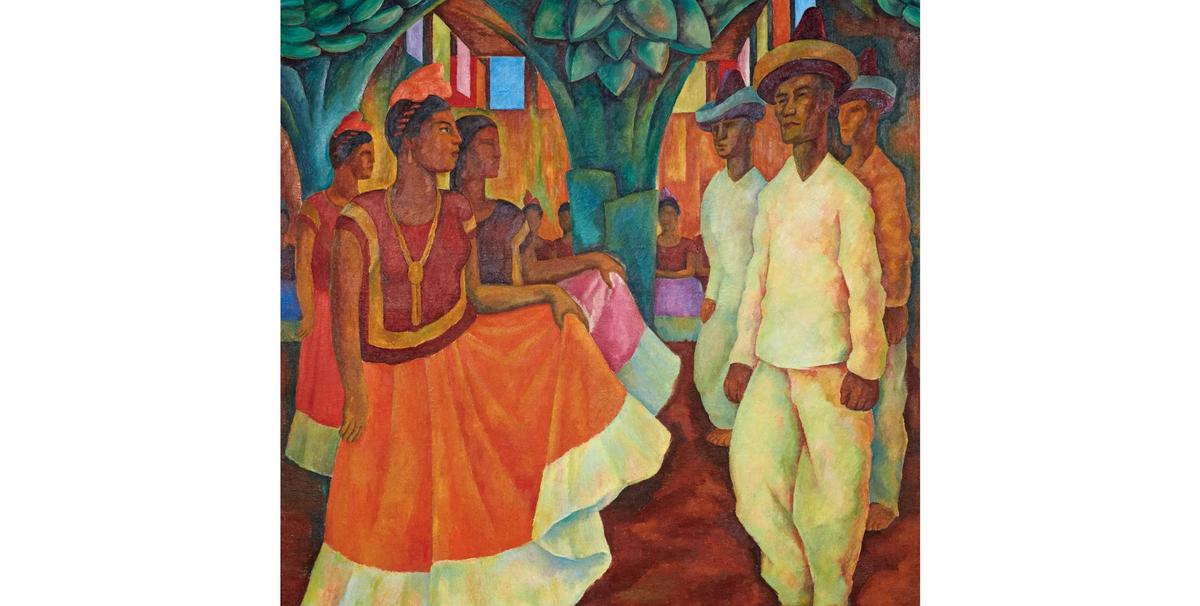

In a private transaction that was later publicised by the buyer, Phillips set a record for a Latin American work when August Uribe, the deputy chairman for the Americas, brokered the $15.8m sale of Diego Rivera’s Baile en Tehuantepec (1928) from a New York collection to the Buenos Aires collector Eduardo Costantini for his Malba museum last May.

However, such deals encroach further on the territory of dealers and independent consultants. Some question the wisdom of allowing the same specialists in charge of filling up sale catalogues to conduct private sales on which they earn commission. In these situations, “there’s always that tension between making the money on a private sale but cannibalising the auction business”, says Mitchell Zuckerman, a longtime Sotheby’s financial services executive who launched Art Market Advisors with fellow Sotheby’s veteran Warren Weitman a year ago. They saw a need for guidance on the consignor’s side as the menu of offerings at auction houses becomes more complex. “If [an auction specialist] says, ‘We like these paintings for auction, but this one is special and it would do better at private sale,’ the next question from us is: what do you have that might compete with that coming into your May auction? We want to see if there’s any conflict or some motivation that isn’t in the owner’s best interest.”

Dolman dismisses the critique. “We work in a very competitive environment. Frankly, the person who gives the best advice to the client normally wins out.”

On a broader level, the focus on private sales is part of an industry-wide push for greater personalisation of the art transaction, making both buying and selling more bespoke and less beholden to the auction calendar. Online art businesses, too, are investigating this model. Artnet recently appointed Alicia Carbone, the former director of digital for Louis Vuitton Americas, as vice- president of auctions and private sales. Late last year data aggregator MutualArt.com merged with the Artist Pension Trust—a private collection of 13,000 contemporary works “deposited” by artists, which after a vestment period it is now starting to sell—to form MutualArt Group. Its chief executive is Mark Sebba, an e-commerce specialist previously the chairman of the luxury retailer Net-a-Porter.

To maximise the return on each work sold from the trust, “We use data to decide when to offer something and what the price should be, and ultimately who it should be offered to”, the chief executive Al Brenner says. “We see private sales becoming more and more important, and we think data gives a big advantage there. So we are looking at opportunities in private sales that go beyond our current activities.”