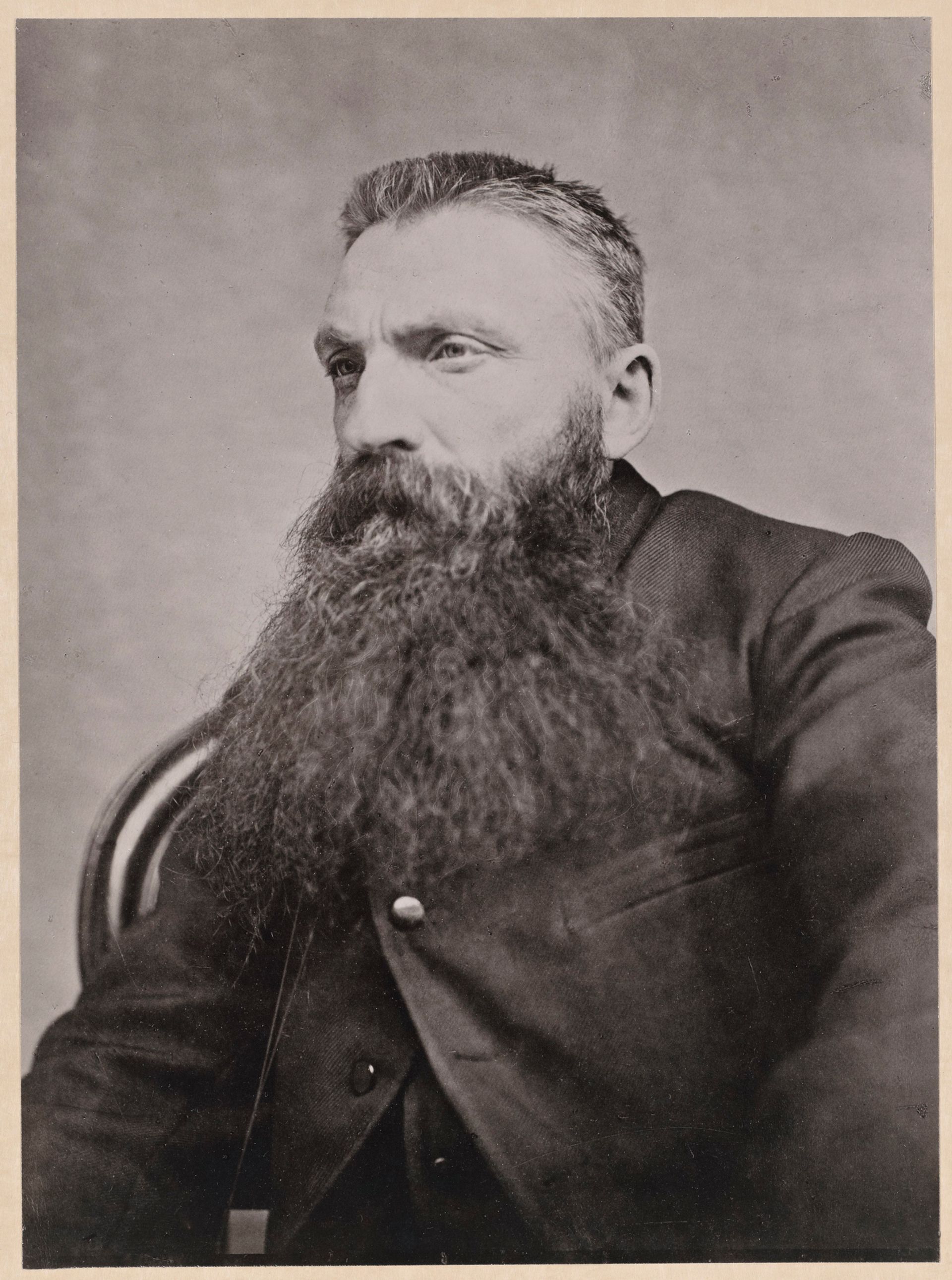

In the century since Auguste Rodin’s death on 17 November 1917, the French sculptor (b. 1840) has been the subject of countless exhibitions and articles, not to mention movies dramatising his jagged love affairs and rugged sculptures. Even more remarkably, considering the adolescent state of the art market at the time, he found great fame during his lifetime, with his last two decades in particular marked by the kind of global success associated with art stars today: international exhibitions, prominent state commissions, a network of private collectors (including the wife of the original “sugar daddy”), headline-making controversies (usually concerning nude subjects) and a large studio operation to sustain them all.

Rodin also had a devoted and deep-pocketed following among Americans, even though he never visited the US. The evidence of that patronage is on full display this year as more than a dozen American museums prepare to stage exhibitions or permanent-collection displays to mark the centenary of the artist’s death.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which opened its first Rodin gallery in 1912 with the help of patrons such as Kate Simpson, Daniel Chester French and Thomas Fortune Ryan (who wrote a $25,000 cheque for Rodin purchases), is bringing works out of storage this autumn for its display of nearly 60 bronzes, plasters, marbles and terracottas. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC will highlight its own Rodin holdings, the core of which were made in Rodin’s lifetime and donated by Simpson in 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, which has 38 works and was one of the first US institutions to own pieces by Rodin, reports that it is planning a “focused show” this autumn.

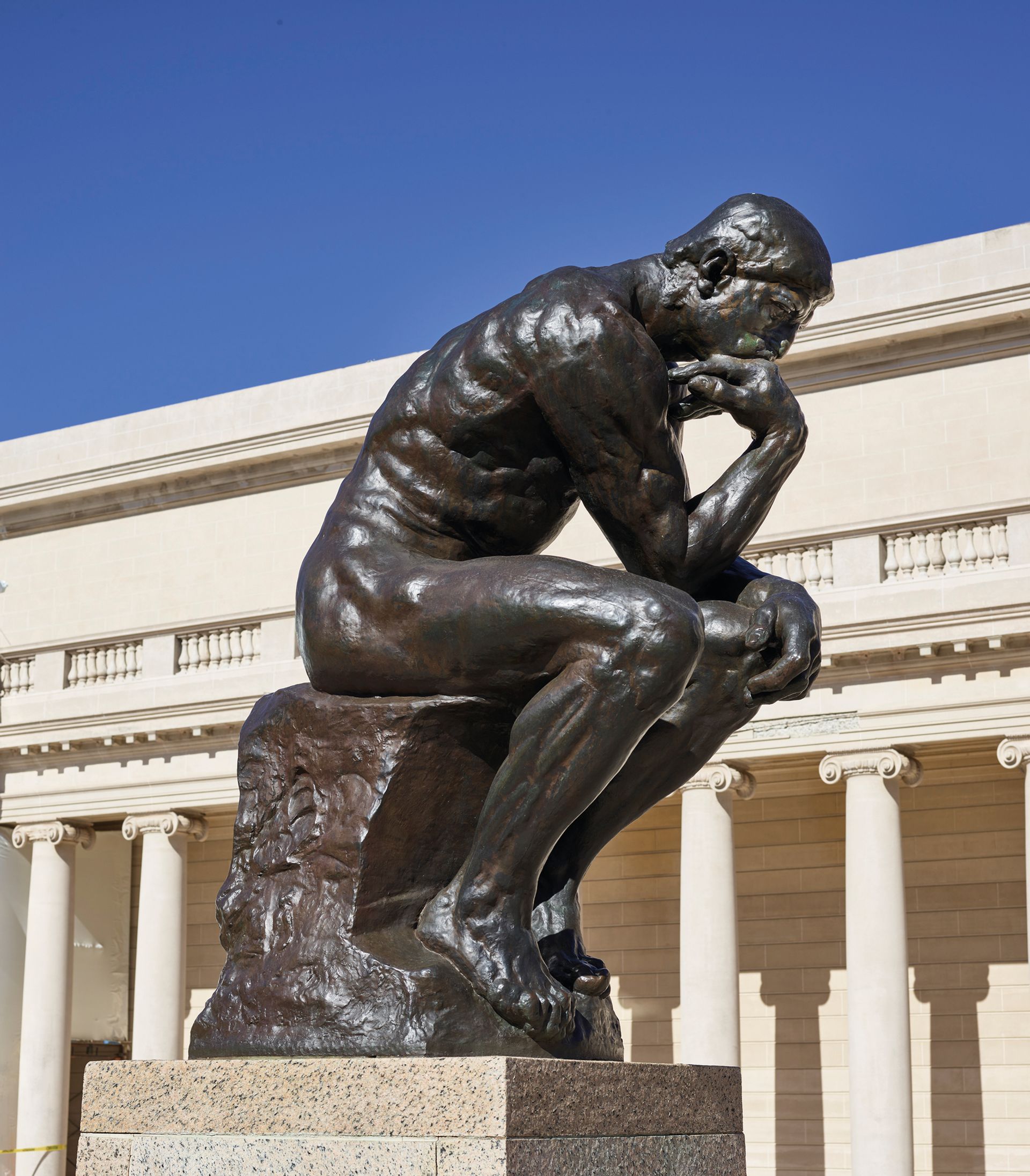

Meanwhile, the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia has just reinstalled its collection, formed primarily after Rodin’s death by the theatre magnate Jules Mastbaum, using passion as an organising theme and its 1929 marble version of Rodin’s The Kiss as the centrepiece. The Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, which has a sizable trove formed even more recently, is also planning a major reinstallation opening in August.

Jennifer Thompson, a curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which oversees the city’s Rodin Museum, says: “Paris, of course, will be a major focal point for celebrating Rodin, but the idea is that if you can’t get to France, you can also see some of his best works in Philadelphia, New York, Washington, DC, Stanford or

San Francisco.”

Pinnacle of Modern art San Francisco’s Legion of Honor (part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)—a museum built because of Rodin in some respects—will have one of the biggest centennial exhibitions. The show aims to tell the story of Rodin’s development as an artist, with 50 objects ranging from a bronze version of Man with the Broken Nose (1863) to small-scale figures from The Burghers of Calais (1885) to the 1907 marble portrait Miss Eve Fairfax (La Nature). These three works, and more, came from the San Francisco collector Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, a struggling artist’s model who married into money when she wed a sugar baron. (Some say she coined the phrase “sugar daddy”.) She got to know the artist through the dancer Loie Fuller, whom she met at a dinner party in 1914.

“During his lifetime Rodin was essentially his own dealer, with most negotiations going through him and Loie Fuller acting as his American agent,” explains Martin Chapman, the curator of the San Francisco show. He describes American interest in Rodin as natural, considering that so many new collectors had big new homes—and new museums—to fill, and Rodin represented the pinnacle of Modern art at the time.

Fuller presented Spreckels to the artist—prematurely or wishfully, Chapman believes—as a serious buyer interested in acquiring work for a new museum, showing him an image of the Spreckels’s mansion in San Francisco’s well-to-do Pacific Heights neighbourhood as though it were a leading arts institution.

The pitch worked. At the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco, the couple not only bought seven sculptures but came away with an idea for their museum’s design. Spreckels fell in love with the French pavilion, a three-quarter-scale version of the Neoclassical Palais de la Legion D’honneur in Paris, and swiftly secured permission from the French government to create a permanent version in Lincoln Park overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge. The building opened in 1924 as the Legion of Honor, and the Spreckels ultimately donated nearly 100 works by Rodin to the museum.

While the Spreckels’s purchase prices were not documented, other early transactions by US collectors were. And Rodin’s prices clearly reflected his fame: in 1902, Kate Simpson paid 25,000 francs for a bust that she sat for, and five years later the newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer paid 35,000 francs for his. (By point of comparison, in 1908 the investor André Level snapped up Picasso’s Les Bateleurs (1905) for 1,000 francs.)

These prices are recorded in the 2011 essay Rodin and his American Collectors by the US scholar Anna Tahinci, who describes several surges of collecting activity in the US: first in Chicago in the 1890s, which benefited the Art Institute of Chicago; then in Boston, which helped the Museum of Fine Arts; and then in New York, which led to the creation of the Rodin gallery at the Met.

Self-made millionaires For the most part, the collectors were “self-made millionaires from the spheres of business, industry and finance”, writes Tahinci. Her chart of Rodin’s American collectors during his lifetime lists 36 names, including the Rhode Island businessman Samuel P Colt (nephew of the gun inventor), Washington Post publishers Eugene and Agnes Meyer, and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the founder of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

The chart also helps to account for the US concentration of Rodin’s Thinker sculptures. Of the 24 larger-than-life, authorised bronze versions, half are in the US, according to the Cleveland Museum of Art, which has one of the few lifetime casts. Another early version, cast around 1904 by Alexis Rudier’s foundry under Rodin’s supervision, is at the Legion of Honor, where it has had pride of place in the museum courtyard since its inauguration in 1924.

THE SCULPTOR'S DEEP-POCKETED BENEFACTORS

THE BIG RODIN ROUND-UP: CENTENARY SHOWS IN THE US AND FURTHER AFIELD

Auguste Rodin: the Centenary Installation

Legion of Honor, San Francisco

Until 9 April

Rodin: the Human Experience, Selections from the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Collections

Portland Art Museum, Oregon

Until 16 April

Versus Rodin: Bodies Across Space and Time

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

4 March-2 July

Masterpieces on the 100th Anniversary of the Artist’s Death

Kunsthalle Bremen

7 March-11 June

Kiefer Rodin

Musée Rodin, Paris

14 March-22 October

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

17 November-12 March 2018

Rodin: the Centennial Exhibition

Grand Palais, Paris

22 March-31 July

Urs Fischer & Auguste Rodin

Legion of Honor, San Francisco

22 April-9 July

Sarah Lucas & Auguste Rodin

Legion of Honor, San Francisco

15 July-1 October

Rodin at the Met

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

5 September-15 January 2018

Gustav Klimt & Auguste Rodin: a Turning Point

Legion of Honor, San Francisco

14 October-28 January 2018

• For a comprehensive list of events to mark Rodin’s centenary, visit rodin100.org