The Armory Show, opening to the public today and running through 5 March at Piers 92 and 94 on the west side of Manhattan, is the subject of scrutiny this year, the first fully under new executive director Benjamin Genocchio, and he has taken pains to distinguish the fair from its global competitors. “This is not a franchise fair,” Genocchio told assembled journalists as the doors opened on Wednesday. “This is a New York institution.”

Gone is the tidy chronological separation between Modern and contemporary art. Pier 92, in addition to hosting the Insights sector for focused presentations of 20th century art, gains some buzz thanks to the curated Focus section and a revamped VIP lounge (de facto segregation remains, however, in that the bigger galleries retain the prime real estate on Pier 94). Observers commented that the overall layout felt more spacious, but it remained to be seen after the VIP opening whether attendees’ pockets were equally deep; many galleries coyly reported sales in the five and low six figures, without the fanfare of years past.

Platform Shines “I’m really pleased,” Eric Shiner, the former director of the Warhol Museum now with Sotheby’s, says of his Platform programme, which scatters monumental works around the fair. “And hopefully it’ll achieve what I wanted, which is to create these moments of surprise, and ultimately to break the monotony.”

Although large-scale sculpture is standard at a many other fairs, Shiner’s selections are carefully calibrated for maximum impact. Yayoi Kusama’s forest of polka-dotted Plexiglas sculptures on Astroturf, Guidepost to the New World (2016), was said to have been sketched on a napkin for the fair, but all the same is sure to be a hit on Instagram (and good luck keeping climbing kids off them this weekend).

At the entrance to Pier 92, Patricia Cronin has restaged her installation Tack Room, first shown at White Columns in 1998, an assemblage that combines themes of horse riding and sexual awakening that raised eyebrows at the opening. (“Because that’s how it happens for the first time, for girls? On a horse?” one man asked, elbowing his female companion. “Well, maybe for the girls in this crowd,” she replied.)

At least two of the Platform works have an element of inherent danger: Dorian Gaudin’s Missing you (2016), a sort of mechanised, Minimalist steamroller at the mouth of Pier 92, and Sebastian Errazuriz’s The awareness of uncertainty (2017), a piano dangling from the ceiling over the champagne bar near the entrance to Pier 94.

Size Matters With so much art on display, it can be hard to entice visitors into any specific booth. A number of dealers went the big-and-shiny route, building booths around a major work, resulting in traffic and spectacle on opening day. This was the case with Pace Gallery, which forewent a normal booth to show Drifter (2017), a work by the collective Studio Drift that consists of a concrete block that levitates within a prescribed space as if carried aloft on air currents. Its asking price was $350,000, and director Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst notes it will be uniquely choreographed for the buyer’s home or institution. (Studio Drift also produced an augmented reality piece with Microsoft’s Hololens for Artsy, across the fair.)

Alan Cristea Gallery has an impressive Howard Hodgkin painting, As Time Goes By (Red) (2009), that spans more than 240 inches, sure to draw in meanderers with its gestural red explosions. Nearby, Jeffrey Deitch has gone all out with a salon-style hanging built around a comparatively diminutive painting by Florine Stettheimer, Asbury Park South (1920). It is a callback to his 1995 presentation at the Gramercy Hotel Art Fair (the Armory’s predecessor), which revived interest in her. This time around, he has added contemporary works—by artists including John Currin, Cecily Brown, Elizabeth Peyton, Chloe Wise, Walter Robinson, and Tschabalala Self—that all seem to collapse into her vibrant work, at its center.

One: not the loneliest number The Armory Show is redefining its relationship with the New York fair landscape, and some galleries seemed to be redefining their relationship with the fair. A number opted for single-artist booths, even though that model is more associated with the ADAA’s Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory, also on this week.

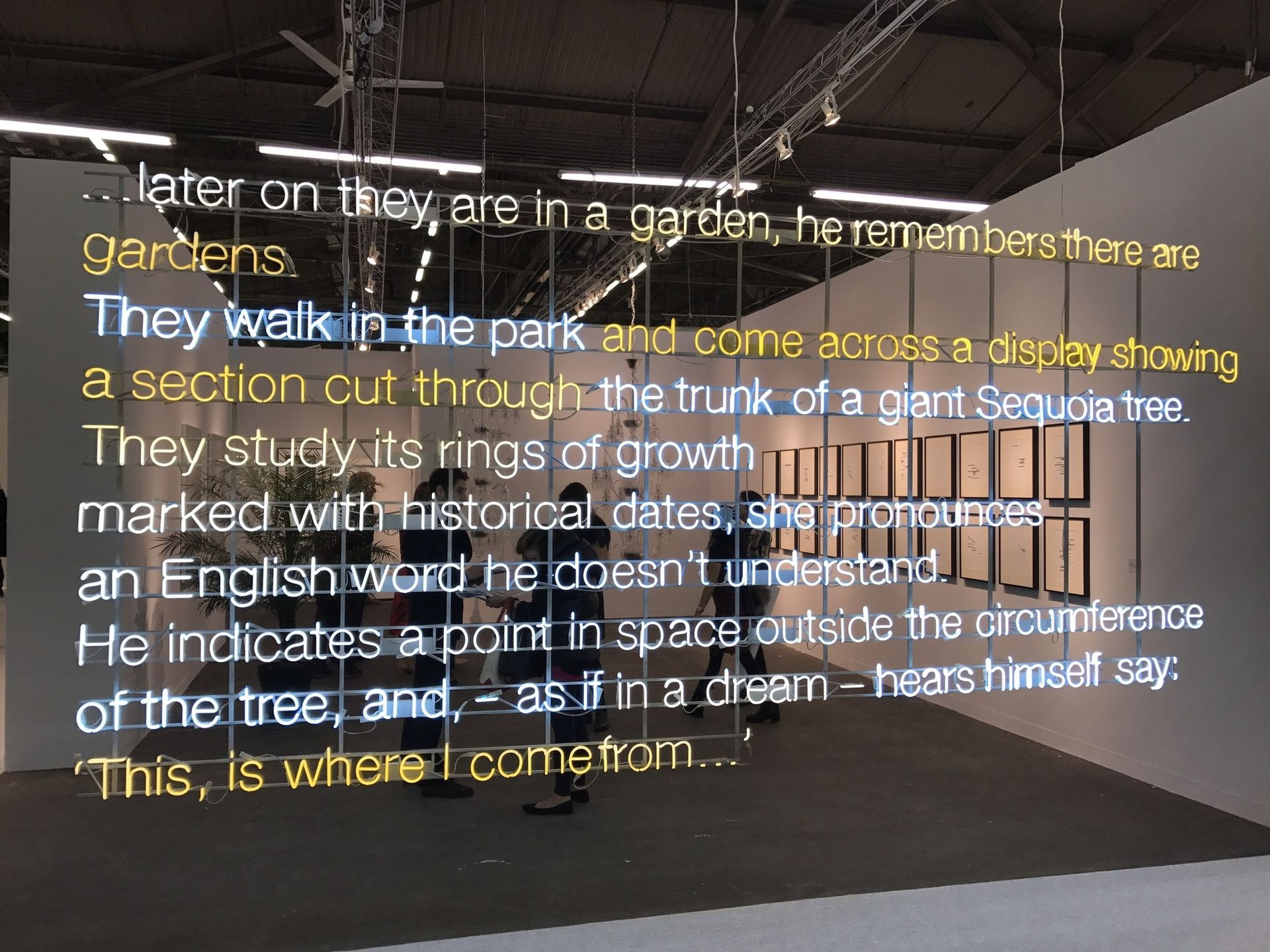

White Cube gave its space over entirely to the diverse work of Cerith Wyn Evans, the Welsh conceptual artist who will unveil a commission for Tate Britain later this month. The artist has a number of museum retrospectives coming up, director Peter Brandt explains, so they thought it was a good opportunity to introduce him to the market. “I think this is the first time we’ve done a solo booth, ever,” he said. The works range in price from $13,000 to $320,000, prices as diverse as the works themselves. These grab your attention first with “...later on they are in a garden...” (2007), a novelistic passage written in neon, to chandeliers and redacted block works on paper.

Around the corner at Galleria Continua, returning to the fair after taking a few years off, the Cuban artist Carlos Garaicoa was on hand to introduce people to his own solo booth (all works around the five-figure range), among the more recent a vitrine of Fortress of Solitude-like architectural models. “It’s great to have a gallery that understands the complex relationships and languages that go into my work,” Garaicoa said.

Axel Vervoordt Gallery’s ode to Gutai-associated performance artist Sadaharu Horio was wildly popular, thanks in part to its ART VENDING MACHINE feature, in which patrons may queue up to buy a work from the artist, who sits in a windowless plywood box that dispenses inky pieces on paper for a single dollar.