Strangely, the capital city of Belgium and the de facto capital of Europe has no dedicated museum of contemporary art. The contemporary collection of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium is mostly in storage amid ongoing renovation. The recent announcement that Paris’s Centre Pompidou will launch a Brussels outpost in 2020 met with mixed feelings from the local art community.

In the absence of a homegrown museum, the Wiels contemporary art centre has become an influential exhibition venue, hosting the city’s first solo shows for international and Belgian artists such as Mike Kelley (2008), Luc Tuymans (2009) and Rosemarie Trockel (2012). Housed in a former brewery since 2007 but with no collection of its own, Wiels is often mistakenly described as a museum, says its artistic director, Dirk Snauwaert. He has used the idea as a jumping-off point for the centre’s tenth-anniversary exhibition, called The Absent Museum.

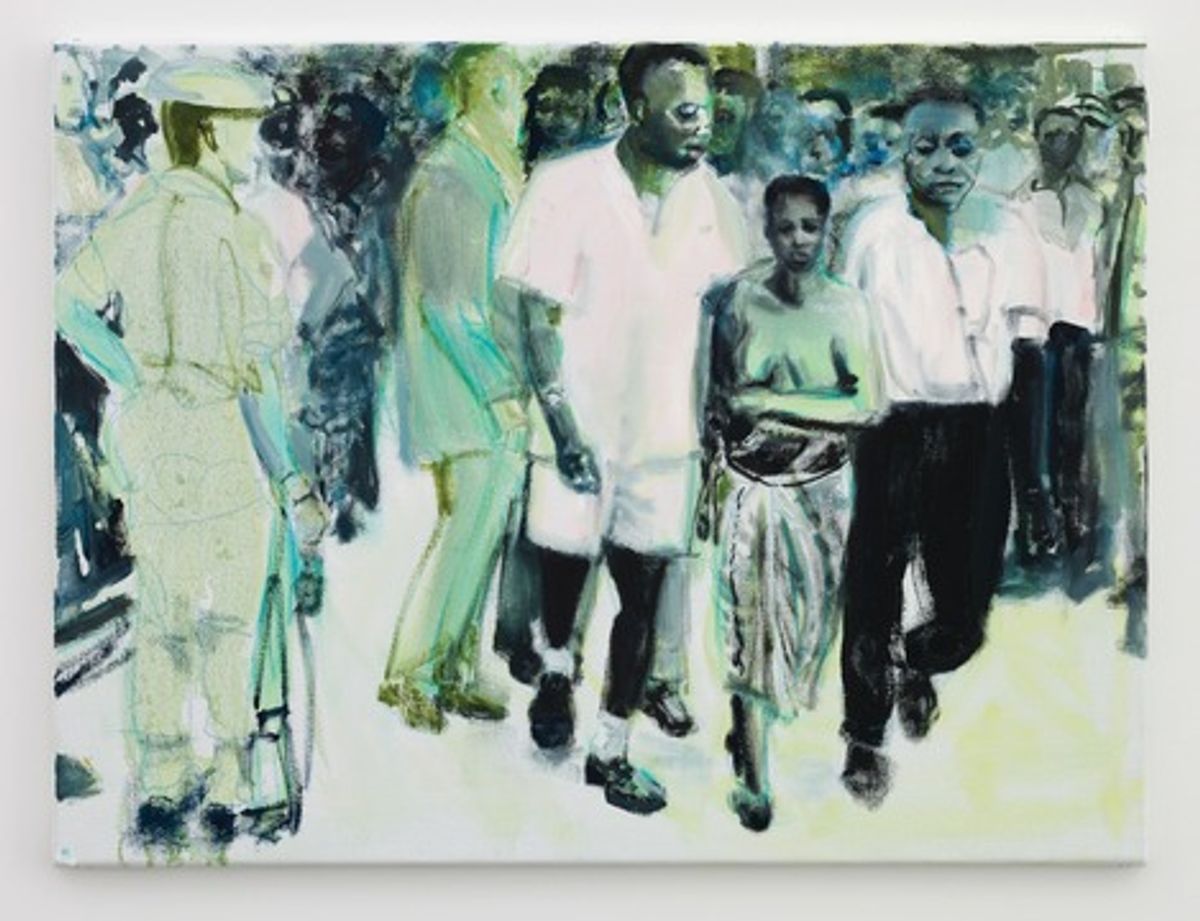

The show will be a biennial-style mix of existing and new works by 47 artists, including Belgian-born “alumni” Francis Alÿs and Jef Geys as well as those new to Wiels, such as Goshka Macuga and Oscar Murillo. Its subtitle—Blueprint for a Museum of Contemporary Art for the Capital of Europe—captures Snauwaert’s broader ambition to imagine the kind of institution that could fill the void. Contrary to the nationalist emphases of many museum collections, the exhibition reflects an increasingly diverse, globalised art world, he says. Participating artists such as the US-born Ellen Gallagher, who has Irish and African-American roots but works in Rotterdam, “make you think twice about our geography”.

As Europe grapples with an ongoing migrant crisis, Snauwaert has also selected works by two artists from earlier generations who confronted “questions of mobility and migration, but also exile”, he says. The German-Jewish Surrealist painter Felix Nussbaum died in a concentration camp in 1944, while the elusive conceptualist Stanley Brouwn was born in the former Dutch colony of Suriname and moved to the Netherlands in the mid-1950s. Brouwn, who has sought to erase his biography and “hates being retrospectivised”, will be represented through a dozen works from his This Way Browun series from the early 1960s, Snauwaert says.

The show has been two years in the making, predating the swift rise of Euroscepticism across the continent. But recent political events have made it more urgent for art institutions to take a stand, Snauwaert says: “We’re trying to invent a kind of cultural, artistic backbone by making shows about ideas that matter.” Wiels staff and other singers will, for instance, perform a chamber opera by Lili Reynaud-Dewar that raises issues of censorship and race relations—one of 17 new commissions for The Absent Museum. “The artists are really still the avant-garde; museums follow,” Snauwaert says.

Among the show’s sponsors are the Fondation Willame, the Mondriaan Fund, the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and the Institut Français.

• The Absent Museum: Blueprint for a Museum of Contemporary Art for the Capital of Europe, 20 April-13 August, Wiels, Brussels