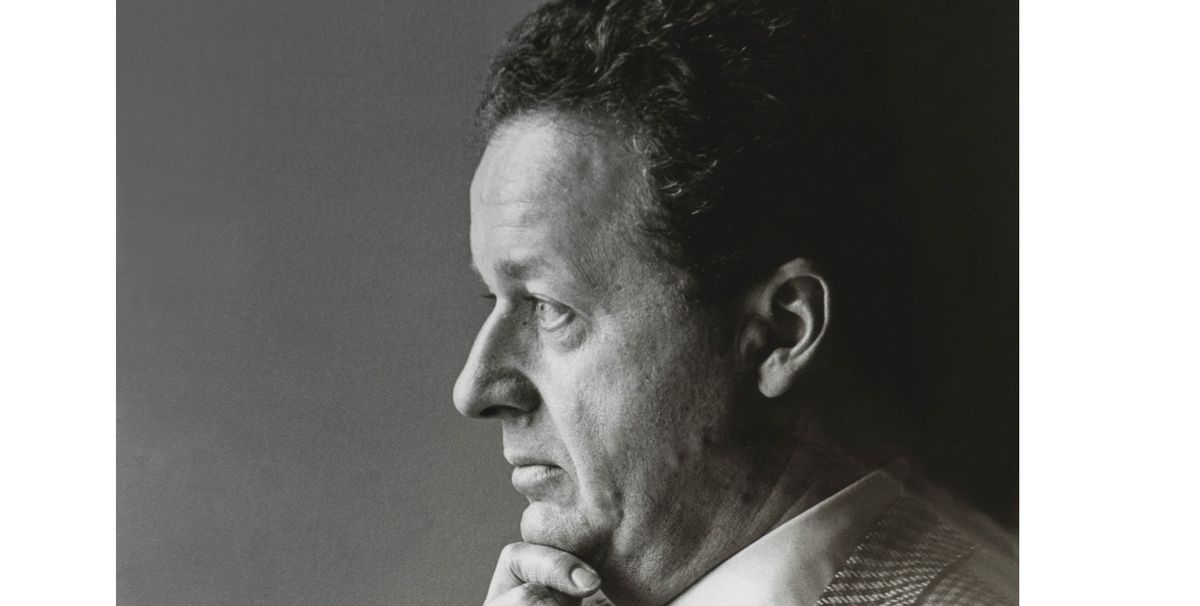

‘Which came first—culture or the homosexual?” This was, albeit tongue-in-cheek, a primary question for Paul Walter, the most cultured of men and exemplar of late 20th-century Homo Manhattanensis, those wealthy aesthetes who were key to New York’s cultural zest.

Walter was physically a giant figure, a “bear” in gay parlance, with voracious appetites, not least for his obsessive collecting of manifold things, ranging from Asian objets and Raj silver to architectural drawings and the art of many styles and eras. If Walter is best remembered as a pioneering photography collector this fact should be saluted as just one of his many gifts within a rich existence of notable largesse.

Walter was a big man with a big life, but the source of his wealth was, by contrast, extremely small, deriving from his father’s invention of the electric igniter that once sparked every gas cooker. As chief executive of his family’s electronics firm, a role inherited in 1968, Walter travelled continuously and became a particularly welcome patron of the European antiques markets.

He was born in 1935 and it was while attending Oberlin College in Ohio that he bought his first works, prints by Whistler. A lifelong interest in India led to Walter forming his first major collection of Mughal miniatures. Both passions fed into his discovery of photography. Whistler brought him to the Pictorialism movement, while European views of India came by logical extension to include early photography, initially inspired by Felice Beato’s images of the subcontinent.

Walter wrote in a 1977 essay on collecting 19th-century photography: “It is one of the few areas left in art—maybe the only area—where you can still put together a major collection of works by major artists. In other areas this is no longer possible, even with unlimited funds, the material just isn’t available.”

Walter was a key player in the small group of collectors, mainly in Manhattan, mainly homosexual, who had at their centre the young connoisseur and dealer Daniel Wolf. Wolf recalls: “Walter defined sophistication in collecting. When he began to collect photographs he was one of maybe five serious collectors. Paul brought to this small and new market an elevated and traditional approach. He was able to focus on the masterpieces, the rare and the unique, and this was something the others learned from. At auctions it was essential to know what Paul bought.”

Walter was a fixture of the London auction houses, sometimes buying large job lots to split with his fellow collectors back home, as Wolf explains: “He was one of the very few who attended the auctions in London when the history of photography was being rewritten because so much material was coming to the market for the first time.”

When Walter pledged 60 prints to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, it was acknowledged as a transformative gift and honoured by the show, A Personal View. It was organised by John Szarkowski, who wrote: “His collection is rich not only in recognised masterpieces, but in pictures of extraordinary quality and interest that had previously been overlooked. Our deepest gratitude goes to Paul Walter for his great generosity, and for his important service to the art of photography and its audience.”

Friends and lovers Walter had a wide circle of friends. A typical anecdote described an adventure with the bloodstained writer Bruce Chatwin in the roughest part of the port of Barcelona; he was particularly close to fellow collector Sam Wagstaff and his lover Robert Mapplethorpe. Walter sent Mapplethorpe the bunch of tulips that inspired his whole series of plant photographs.

Walter also became close to one of Wagstaff’s other boyfriends, the architect Mark Kaminski, who he suggested should stay with him in Tangiers at the Forbes mansion. Kaminski sent Wagstaff a postcard from Morocco to explain he was actually there with Walter, who was subsequently teased by Wagstaff for having “stolen” his boyfriend.

Walter and Kaminski were together for 17 years and between them created a series of extraordinary residences, at the Campanile on East 52nd Street, New York, and their estate, Redcroft, in Southampton, Long Island.

The latter was very much to Walter’s taste for Arts and Crafts and late Victoriana: he could not help himself assembling a nonpareil collection of furniture of that period, including items by Lutyens, William Benson, Godwin, Dresser and Morris. At the same time Walter was perfectly at home in a more minimal mode, whether with furniture designed by director Robert Wilson or paintings by the likes of Brice Marden.

When Kaminski died of Aids aged 39 in 1993, Walter had just begun divesting himself of some of his many collections, having held a sale the year before of his Surinomo prints. Many of his remaining photographs were sold at Sotheby’s in 2001, an auction which broke existing records and made more than £2m. His Indian miniatures, exhibited at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1976) and the Morgan Library (1978), were auctioned off in 2002.

Walter’s final collection was devoted to vintage postcards inspired by an early example showing his house in the Hamptons, and typically he helped create, and boost, this otherwise modest market. Daniel Wolf has the last word: “Paul’s personality was his greatest asset: charming, funny, engaging and generous. He was loved in the art world.”

• Paul Walter, born 1935, died 6 January 2017