The main exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale (13 May-26 November) will feature six artists from mainland China, forming one of the largest contingents in the show Viva Arte Viva, which is being organised by the Centre Pompidou curator Christine Macel.

While the number of Chinese artists in the main exhibition has varied, in recent years China has gone to considerable lengths to ensure a strong presence in Venice while the city hosts the biennial. In 2013, for example, there were ten shows of Chinese contemporary art throughout the city (in addition to its own pavilion), with a total of nearly 350 artists showing. At the last biennial in 2015, China even took over the pavilion of Kenya (a country where China has multi-billion-dollar investments): the work of two Kenyan artists was on display alongside pieces by six Chinese artists.

This year, the Chinese participants in the main show, announced in February, range from Chinese contemporary art trailblazers Geng Jianyi and Liu Jianhua to rising stars Guan Xiao and Hao Liang, who were born in the 1980s.

“I feel the six artists are all quite different,” says Liu, who was born in 1962 in Jiangxi province. “I know Geng Jianyi and Liu Ye well—we’re about the same age. Since 1985, Geng Jianyi has never stopped doing art with his own language and ideas… The younger artists are very vigorous, and artistically unique.”

A founder of Chinese contemporary art, Geng was among the ten Chinese artists to first exhibit in Venice in 1993, alongside Feng Mengbo, Xu Bing and Wu Shanzhuan. The 1999 biennial proved another watershed for China, when the curator Harald Szeemann included 22 Chinese artists, including Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Chen Zhen, Wang Xingwei, Zhang Huan, Zhang Peili and Zhou Tiehai. Their participation heralded Chinese contemporary art’s global emergence in the 2000s.

Liu Jianhua was meant to participate in the inaugural China Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale. But the pavilion was cancelled due to the outbreak of Sars that spring and the show was instead held at the Guangdong Museum of Art. There, Liu Jianhua debuted his Regular Fragile series of porcelain replicas of daily objects. He says: “It was a very dramatic situation, with the first time in Venice but not actually at Venice.” This year, he anticipates, will be “a very different feeling. The conversation is bigger—now I get to go to everything, have a dialogue with other artists and a larger communication, and see a lot of interesting art.”

Shanghai-based Liu studied ceramics for 14 years in Jingdezhen, the traditional hub of that Chinese craft. His sculptures and installations of the early 1990s through to the late 2000s included pointed commentary on China’s social and political conditions. For the past decade, he has veered into more personal and abstract ideas. However, his Polit-Sheer-Form Office collective, with the artists Song Dong, Hong Hao, Xiao Yu and the director of Pace Beijing, Leng Lin, remains cheekily topical, with events such as their volunteer mass mopping of Times Square, New York, to juxtapose communist values of public service in the centre of capitalism (Do the Same Good Deed, in 2014).

Geng Jianyi, born in 1962 in Henan Province, helped shape the emergence of contemporary art in China and particularly Hangzhou, where he has lived since 1985. Part of the 85 New Wave movement, he started out creating some of Chinese contemporary art’s most iconic works, including the four creepily laughing heads of The Second Situation (1987), before shifting into installation and new media.

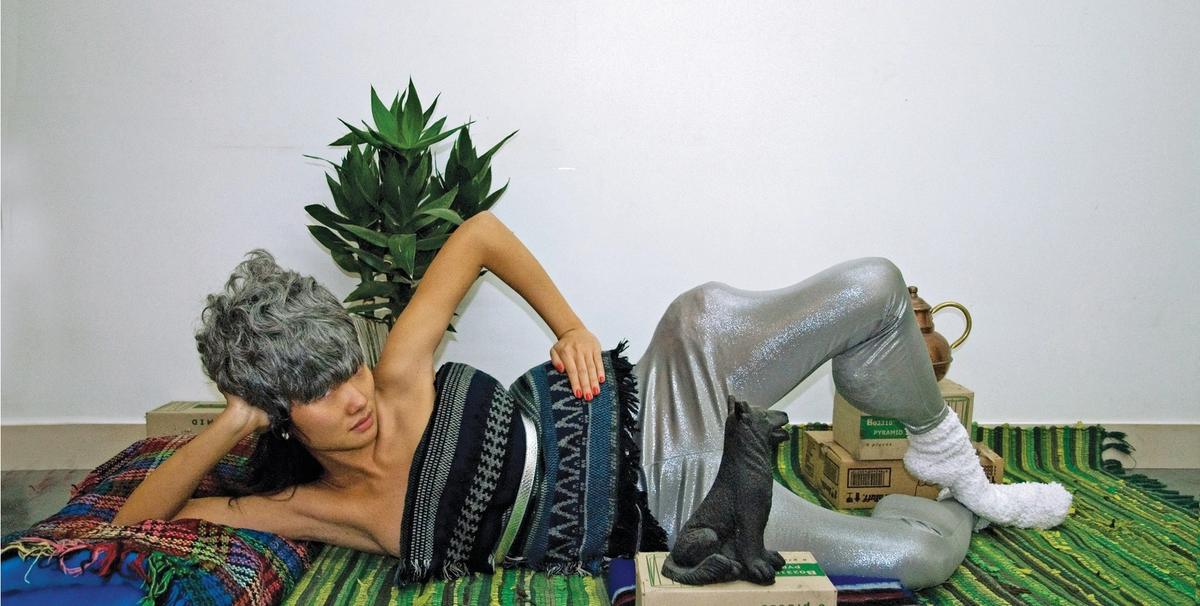

Part of Chinese contemporary art’s second generation, the Guangzhou-based Zhou Tao, who was born in 1976 in Changsha, works mostly in video and performance, often exploring the idiosyncrasies of daily urban life. Guan Xiao, born 1983 in Chongqing, similarly focuses on the personal experiences of a fast-changing culture, with bright colours and bold visuals as signatures of her installations.

A modern painter with a more traditional bent, Beijing born (1964) Liu Ye creates cartoon-like images women and children, sometimes posed in front of works by Mondrian. Hao Liang, meanwhile, taps the tradition of Chinese ink art. Born in 1983 in Chengdu and now based in Beijing, his paintings evoke ancient China stylistically while incorporating Western techniques.

Shadow play will animate the Chinese Pavilion The Chinese Pavilion is being organised by the artist, curator and teacher Qiu Zhijie. Qiu participated in the main Venice Biennale in 2009, and a satellite show in 2013; this year he will organise a collaboration between the contemporary artists Tang Nannan and Wu Jian’an and traditional artisans Wang Tianwen and Yao Huifen in Continuum: Generation by Generation.

“Contemporary and traditional arts shouldn’t be separated,” Qiu says of the Chinese Pavilion exhibition. “Chinese contemporary artists, myself included, always have a mix of both, but people create a dichotomy.”

Wu and Wang have collaborated for several years, and the four artists with Qiu will present a live shadow play. Referring to Suzhou embroidery expert Yao and shadow puppet master Wang, the curator says: “Chinese traditional art is both craft and art, so they are artists; it is not appropriate to call them just craftsmen.” He says that art in the Chinese tradition was about ongoing interaction and discussion, rather than a singular product from an individual. Qiu himself is best known for his highly theatrical installations. He is also the director of Shanghai’s performance-focused Ming Contemporary Art Museum. “More than video, theatre provides a special way to engage the audience,” he says.