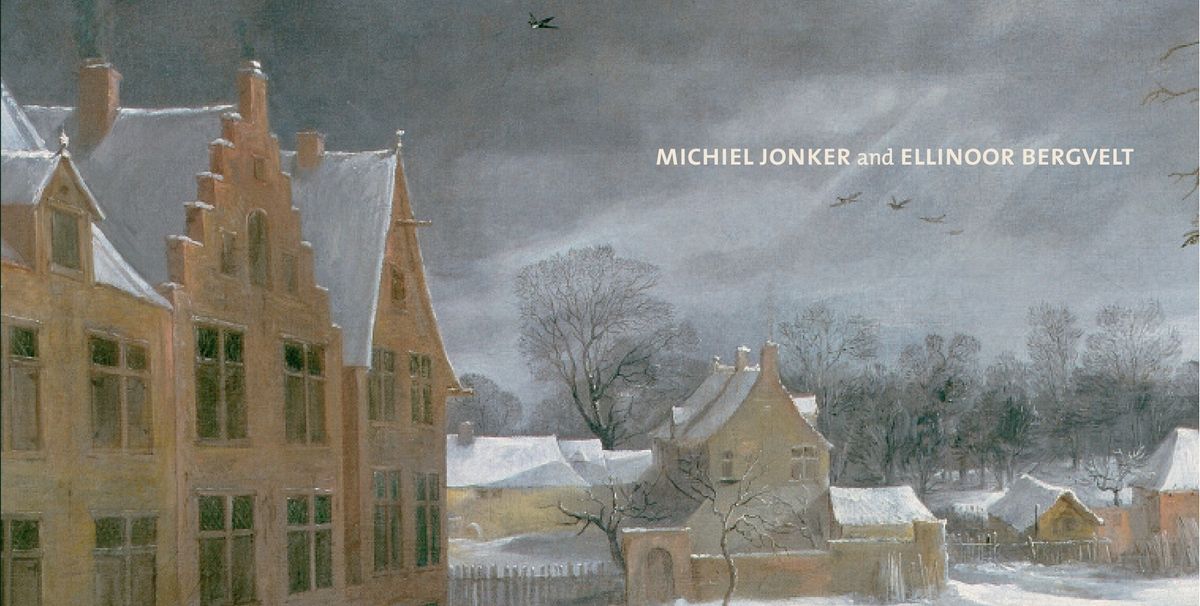

Dutch and Flemish Paintings: Dulwich Picture Gallery

Michiel Jonker and Ellinoor Bergvelt

Giles in association with Dulwich Picture Gallery, 352pp, £49.95, $79.95 (hb)

The publication of a scholarly collection catalogue is always to be welcomed, particularly during straitened times for art-history publishing. Dulwich Picture Gallery belatedly began to produce school catalogues of its extensive holdings in 2008, with John Ingamells’s study of the gallery’s British paintings, This splendid first catalogue of its Dutch and Flemish paintings, written by Ellinoor Bergvelt and the late Michiel Jonker, provides entries on 228 works, which range in quality and renown from Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window to crudely painted works from the Cartwright bequest, many of them copies made in London during the 17th century. The entries are succinctly written and include full provenance and bibliographic references for each painting, as well as technical notes.

An opening essay by Bergvelt traces the formation of the Netherlandish collection at Dulwich. Almost 75% of catalogued paintings were acquired by the dealers Noel Desenfans and Sir Francis Bourgeois, many of them on behalf of the ill-fated King of Poland, Stanislaus Augustus, before they decided to bestow their benevolence on Dulwich College. Since Desenfans and Bourgeois made most of their purchases in the years after 1789, at a time when London auction houses were inundated with paintings from aristocratic Parisian collections, it is hardly surprising that there is a distinct French prejudice for Dutch Italianate landscapes, particularly those by Nicolaes Berchem and Philips Wouwerman, and for the rustic scenes of David Teniers the Younger. Aelbert Cuyp was also a favourite. There are few startling revelations in this catalogue; it is more a question of consolidating in one place information already available on the individual works. New attributions are restricted to minor paintings and relatively obscure figures, such as Dirck van Bergen, Karl Wilhelm de Hamilton and Jan Frans van Son. Recent X-radiography has, however, provided some insight into the evolution of paintings such as Anthony van Dyck’s Samson and Delilah, and Rubens’s Venus, Mars and Cupid. In addition, there is an occasional new interpretation of subject matter. For example, the figures in a church interior painting by the workshop of Pieter Saenredam represent, in the view of Jonker and Bergvelt, a burial ceremony rather than a baptism, as has been long assumed. Such meticulous scholarship is a fitting testimony to Michiel Jonker’s memory.

• John Loughman is the senior lecturer in art history at University College Dublin

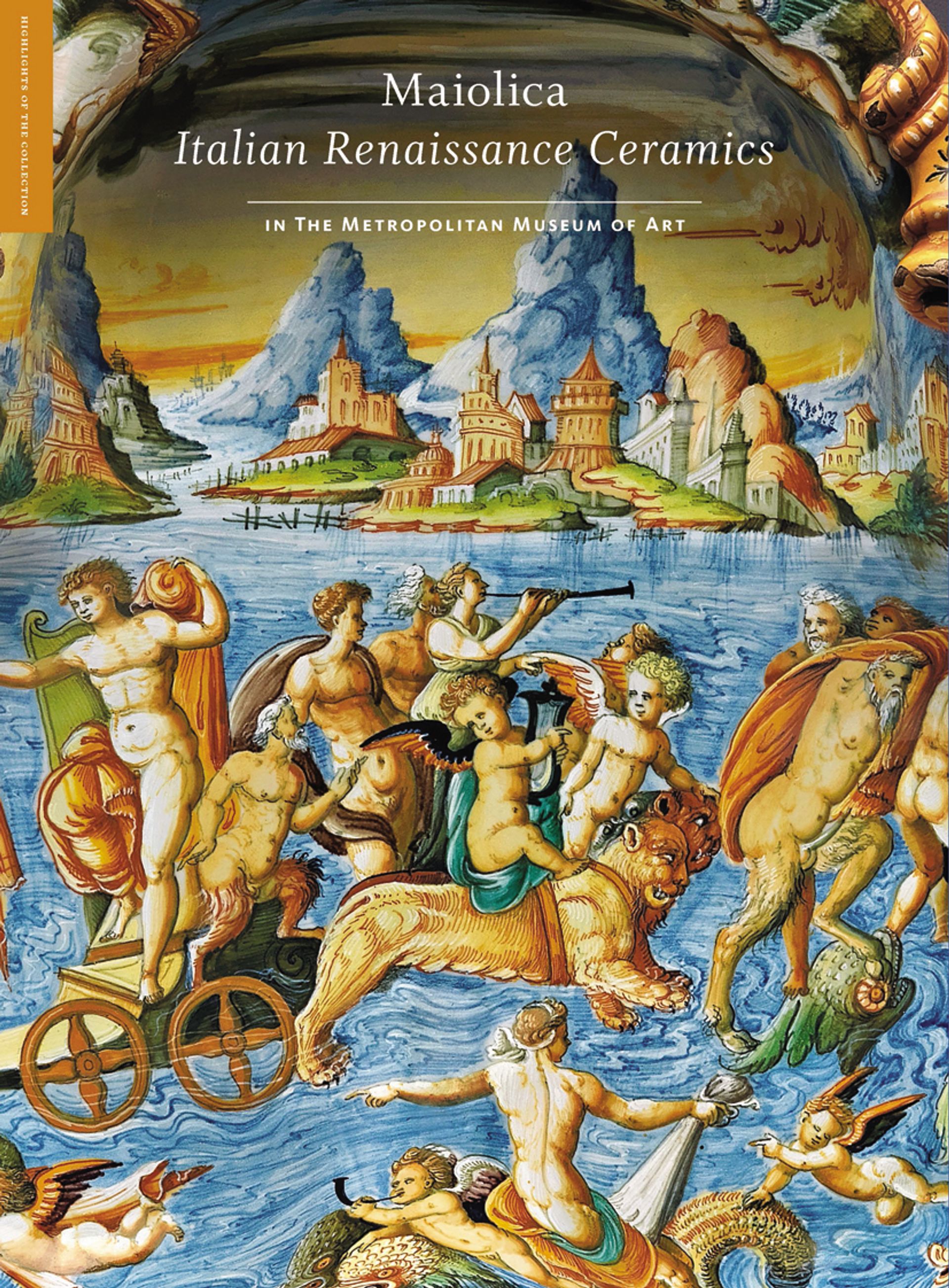

Maiolica: Italian Renaissance Ceramics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Timothy Wilson with an essay by Luke Syson

Yale University Press in association with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 392pp, $75 (hb)

This book presents 135 star pieces from the world-class collection of Italian Renaissance ceramics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is a scholarly catalogue that includes pieces ranging across all the major categories of tin-glazed ceramic—maiolica—from pharmacy jars to a group sculpture of the Lamentation, as well as some of the finest examples in the world of Florentine soft-paste porcelain, which was highly sought after by 19th-century collectors such as the French Rothschilds. There are excellent photographs and full exhibition and provenance details; each entry also offers a survey of the latest scholarship. The catalogue is, however, highly accessible; it reads fluently and is inviting to the eye.

The discovery of Italian maiolica by the greatest collectors and patrons of Europe is traced in Luke Syson’s essay “Composing for Context”. Much of this summarises recent research in a thoughtful and questioning way, considering the aesthetic status of maiolica as opposed to its price, as well as its display in town and country, and use at table. The most original section looks at the diversification of forms, as tastes in serving and dining developed among the urban elites in Renaissance Italy. Timothy Wilson provides an overview of maiolica production and its technical development, and introduces the Metropolitan Museum’s collection as “by far the finest in America”.

The collecting of maiolica in Europe reached a peak in Europe in the 1870s, when the museum was founded. Wilson credits the Metropolitan’s assemblage to New York collectors such as Pierpont Morgan and Mortimer Schiff, who were able to buy from major European collections formed in the 19th century as these were dispersed on the art market in the first quarter of the 20th century. American collectors took up the tastes of the great collectors of the mid- to late 19th century and the dealers who had supplied them. As prices for maiolica, and its prestige, fell just before the Second World War, the Metropolitan Museum bought vigorously.

This book will be invaluable to students and scholars alike in introducing a superb collection.

• Dora Thornton is the curator of Renaissance Europe at the British Museum and of the museum’s Waddesdon Bequest gallery, supported by the Rothschild Foundation

My Life as a Work of Art: the Art World from Start to Finish

Katya Tylevich and Ben Eastham

Laurence King, 336pp, £18.95, $28 (hb)

As Katya Tylevich astutely observes, explanations of contemporary works, especially as given by the galleries that represent the artists who make them, either detract from the works or have “no effect on the clarity” of them; they are “a collection of art-jargon bits strung together”. So, too, is much other writing about contemporary art. There are any number of books on contemporary art in print, but Tylevich and Eastham’s is different—and far more nourishing than most.

The authors have taken eight works of art and analysed them in depth, following them “like a nature documentary-maker, from beginning to end”, as they write in the introduction. The works are diverse, from one by maverick conceptualist Martin Creed, through a little-known (but, as Tylevich convincingly argues, significant) performance-cum-installation by Marina Abramović, to a collaborative project by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe.

The eight essays are neat fusions of memoir, social history and reportage. Tylevich conveys the cultish aura surrounding Abramović and the artist’s lurches into irritating quasi-spiritual mumbo-jumbo, while also testifying to the enduring impact of Abramović’s Dream House on the small Japanese village in which it stands, and on Tylevich herself after she visits it. Eastham’s study of Creed’s Lights Going On and Off involves conversations with the artist; with a member of the jury that awarded Creed the Turner Prize after he showed the work at Tate Britain in 2001; with a woman who threw eggs at the Tate’s wall in protest at Creed and the “dreary state art” championed by the museum; and with visitors experiencing the work today. He also expands his discussion into conceptualism and the bizarre nature of negotiations for works that are simply a set of instructions. (In the case of the Creed work, these read: “An empty room; lights on for five seconds; lights off for five seconds; repeat.”) Elsewhere, Parreno and Huyghe’s project No Ghost Just a Shell prompts Eastham’s journey into the nature of copyright and authorship; what could be a dull subject is dealt with fascinatingly.

At times, the duo’s desire to avoid leaden prose leads to self-conscious chattiness, but for the most part they explore contemporary art, and the varied contexts in which it can be experienced, with writing that is passionate, original, perceptive and clear. And those are values inherent in all the best art criticism.

• Ben Luke is the features editor of The Art Newspaper and an art critic at the London Evening Standard