Roger Hiorns, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (until 5 March)

Roger Hiorns is the master of altered states: most famously he transformed an abandoned South London council flat into a miraculous grotto of blue copper sulphate crystals. There is some copper sulphate in his current exhibition at the Ikon Gallery in his native Birmingham, but this time covering a piece of hardboard and accompanied—the label informs us—by “brain matter”. The ominous material is also painted in yellowish streaks across a square of white board and invisibly inserted into the stripped-out engine of a Toyota car. Hiorns’s preoccupation with such a scary substance stems from his long-standing interest in the so-called “mad cow disease” of the 1980s and 1990s. This, as we learn from a disturbing interview with a neurology professor that plays on a wall-mounted monitor, is an epidemic whose effects still have not been fully addressed and dealt with.

In this compelling, unsettling show all the works feed into and off each other, sparking a chain reaction of potent associations. Something devastating seems already to have happened to the pair of life-sized mannequins that dangle from a nearby wall, kept aloft by the force of electro-magnets which are intermittently turned off, causing them to crash resoundingly onto the floor. There is more bodily action in a series of new paintings made from flesh-coloured plastic and latex depicting the gloopy primeval forms of naked male figures having extravagant sex with themselves and each other, as well as in the arrival—at regular weekly intervals—of young naked male performers who calmly interact with the exhibits.

In the world of Hiorns, as in our own, nothing is stable or certain. An undulating field of grey dust resembles an arid aerial landscape but is in fact the pulverized engine of a passenger jet. A series of dangling bodies made from salvaged plastic containers seep perfumed foam, while an engine is shown intact but impregnated with antidepressants. In this memorable show our expectations of familiar objects and materials are repeatedly destabilised as the alchemy of Hiorns’s work forces them to take on a new and often problematic life of their own.

Richard Wilson: Stealing Space, Annely Juda Fine Art, London (until 25 March)

One of the most original and significant artists working today, Richard Wilson’s 20:50 (1987), a room full of sump oil, is up there with Walter De Maria’s Earth Room (1977) and Joseph Beuys’s Plight (1985) as one of the all-time great sculptural installations of the 20th century. And let’s not forget his 80-metre, 77-ton sculptural solidification of a plane trail called Slipstream (2014), which fills the entrance to Heathrow airport’s Terminal 2. But although he is a Royal Academician and admired by his fellow artists, Wilson is not nearly as well known as he should be. And in the art market he has virtually no presence at all.

Which is why Wilson’s current exhibition at Annely Juda is so welcome. It is not easy to show work devoted to reconfiguring space, but the Juda gallery has risen to the challenge with four new sculptural pieces that almost entirely fill the gallery. Two of these are made in direct response to the gallery’s internal and external architecture. One is a wooden solidification of the space between the hallway and staircase leading up to the gallery’s main entrance, which sprouts architectural details and sits on the floor, tilted at an angle. The other, called Block of Dering (2017), takes the Dering Street façade of the gallery building and reconfigures it into a near-cube.

The hulking, cuboid Space between the Door and the Curtain renders the interior of the artist’s London home in blocks of birch ply MDF. Smaller in scale—if still monumental in appearance—is a wooden household cabinet that has been meticulously sliced and remade into what looks like a brutalist apartment block.

There are also finely-made collaged drawings for these projects, as well as exquisite maquettes for some of Wilson’s other best known works. These include Slice of Reality, a vertically-sliced chunk of a Thames dredger which is now moored on the Thames in Greenwich, and Turning the Place Over, in which Wilson cut a 10-metre circular section from the façade of a Liverpool apartment block that then spins outwards 360 degrees above the street below. These not only illuminate the workings of this most unique of minds, but also stand as rather more easy to house artworks in their own right.

Lubaina Himid: Invisible Strategies, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford (until 30 April) and Lubaina Himid: Navigation Charts, Spike Island, Bristol (until 26 March)

They may have been a while coming, but Lubaina Himid’s two simultaneous survey shows don’t disappoint. A key figure in raising the profile of black British art, Himid describes herself as “a filler-in of gaps” and she has spent the last three decades making work and organising shows devoted to uncovering marginalised histories and figures, while her own work has not had the attention it deserved.

The Modern Art Oxford exhibition steers a vibrant course through what has nonetheless been a prolific and multifarious career. There are sculptures, prints, customised newspapers and the freestanding board cut-outs for which she is best known. One room contains a collection of 18th- and 19th- century bone china painted with vivid portraits of slaves, slave markets and cartoons based on James Gillray’s cartoons mocking the supposed perils of the abolitionist movement. In a gloriously mixed media piece from the 1980s, two colossal black women directly lifted from Picasso’s bathers are painted onto a pink sheet as they hurtle across a beach in dresses made of airmail envelopes. The figures, dragged along by a pack of dogs, kick sand in the faces of a pair of doleful white men buried up to their necks.

The Spike Island show is dominated by Naming the Money (2004), Himid’s 100-strong crowd of brightly painted life-sized figures that stride, cavort and play a variety of instruments and represent the Africans who were brought to Europe as slave servants. Labels on their backs identify each individual, giving both their original African names and occupations as well those imposed by their new European owners. These poignant texts form part of an evocative soundtrack, interspersed with snatches of Cuban, Irish, Jewish and African music. More uncomfortable connections between industrial wealth and human suffering are also underlined in the work Cotton.com, which is a wall covered with around 70 tiny black and white paintings that represent imagined conversations between the cotton workers of Lancashire and the cotton slaves of South Carolina.

Yet at the same time as Himid’s work forms serious—and often searing—political and historical commentary, it is also fired with an irrepressible joie de vivre. Amidst all her many media, she is at heart a painter. Her formal acuity, and love of colour and pattern, runs across whatever surface she happens to be using, with engaging as well as thought-provoking results.

Michael Andrews: Earth Air Water, Gagosian Gallery, London (until 25 March)

Michael Andrews was a friend and contemporary of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach, all of whom greatly admired his work. But he never enjoyed anything like their acclaim in his lifetime and his reputation still unjustly lags behind. For, as this wonderful exhibition of his intense, dreamlike and utterly distinctive paintings confirms, this relatively low profile had more to do with Andrews’s reserved character and fastidiously slow working method—when he died in 1995 at the age of 66, his total oeuvre was fewer than 250 paintings and watercolours—than any lack of quality.

A rigorous researcher, virtually all Andrews’s larger paintings emerged out of an exhaustive period of intense observation and adjustment, backed up by photographs, notes, sketches and watercolours made on the spot. Not since Turner strapped himself to the mast of a ship in the middle of a storm has a British artist so immersed himself in the elements of what he aimed to depict. In Scotland this meant crawling through bogs and mountainsides in the driving rain; in Australia clambering on, and nearly falling off, Ayres Rock; or wading in the mud by the Thames. The result is work that shimmers with the almost religious strength of this engagement.

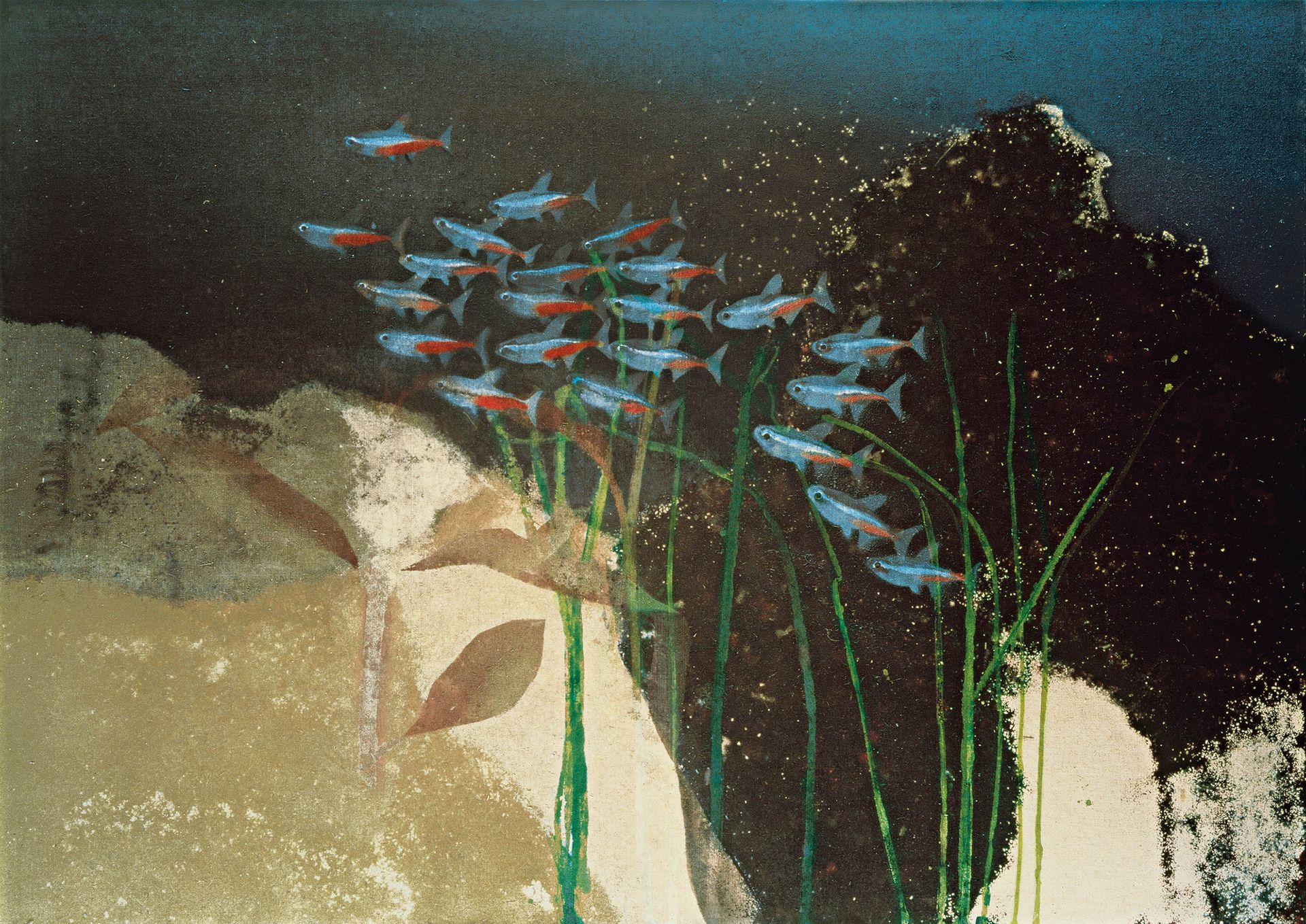

However, this laboriousness was always worn with the utmost lightness. In Andrews’s limpid and luminous late works, both his oil and his acrylic paint (and sometimes a mixture of the two) became ever thinner and increasingly devoid of expressive gesture. He even used spray guns to stain his unprimed canvas with mists of evanescent colour. But while his methods might have been as self-effacing as his personality, this only made the presence of the finished work become more haunting and powerful. It did not matter whether Michael Andrews was painting parties, panoramas or shoals of fish, he firmly believed that “all is subject to atmosphere”.