Velázquez Portraits: Truth in Painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small show that packs a big punch. It is the antithesis of a blockbuster, and like others of its kind, is an effective antidote to museum fatigue. More is demanded than a stroll through the galleries—namely the studied engagement with a small number of works per visit. The organiser is Met curator Stephan Wolohojian, who has assembled a mere six Velázquez paintings: three from the permanent collection of the Met, two from the Hispanic Society of America, one from a private collection. A seventh work, also from the Met, is attributed to a follower.

The publication of the complete catalogue text is only found on the Met's website. The benefit of this use of technology is obvious: it is inexpensive and is capable of augmenting the distribution of ideas by a very large factor, indeed. While it is true that informative wall texts help to guide visitors through the show, with an iPhone in hand, the entire catalogue is eminently accessible. I hasten to add that it would be very helpful if reference to the online catalogue could be made available in the gallery.

Velázquez was a notoriously unproductive painter. His principal patron, Philip IV, was well aware that he worked at a slow pace. He attributed this habit to Velázquez's flema, or laziness, and surprisingly learned to tolerate it. This means that even a small show can reveal salient aspects of Velázquez's artistry.

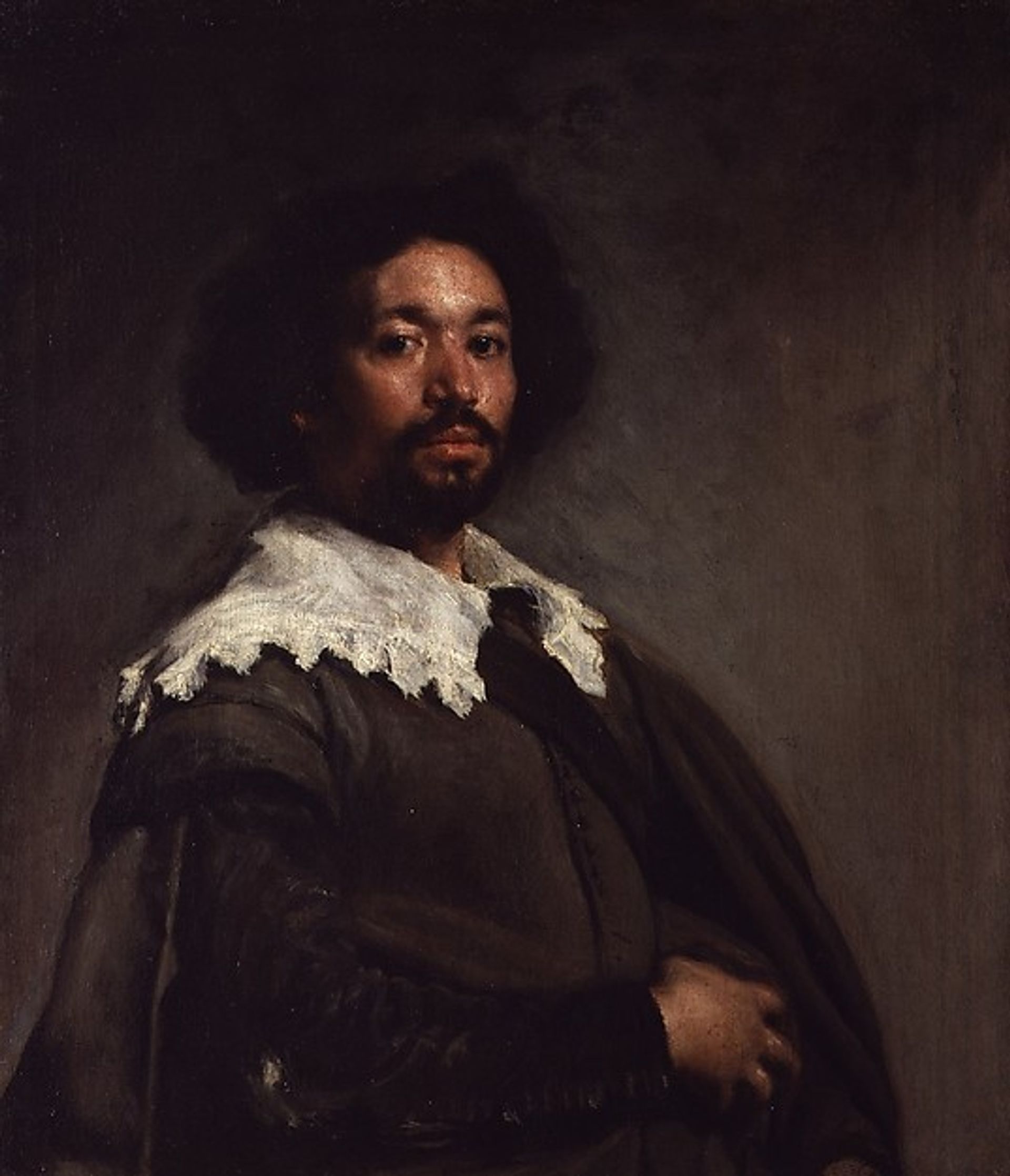

The theme of the exhibition is portraits of bust-length or half-length. The star, of course, is Juan de Pareja, painted in Rome in 1650. In a recent seminar, I challenged students to stand in front of the painting for an hour and analyze its technique and artistry. Time flew. So compelling is the image that one scarcely notices that the sitter’s left hand resembles a claw; not a single finger is observable. The mind processes what the eyes see. More daring still is the rendition of the ear, which is little more than a blob of pigment. I consider it to be one of most drastically abbreviated anatomical details in all of 17th century painting. (Viewers may judge this claim by looking at the adjacent runner-up, the Portrait of Camillo Massimi-Pamphili, painted around 1650.) The tonalities of the cloth are rendered in a spectrum of dark greens, which are only noticed if one stands in front of the canvas.

Another star is the Portrait of a Young Girl (around 1640) from the Hispanic Society. It was in fact, the recent restoration of this charming portrait that inspired the show. Here again, it pays to go the website, where there is pellucid account of the recent cleaning by the Met’s conservator, Michael Gallagher. Gallagher, who is a superb writer of expository prose, takes us step-by-step through the treatment of the picture. Once the veil of discolored varnish is lifted and the small losses filled, the sitter returns to life.

The Portrait of Camillo Massimi-Pamphili is another modest tour-de-force, if there can be such a thing. The richness of his red robe was achieved by modulating the color of his vestment. Very striking is the tilted position of the biretta, which imparts an almost jaunty look to the sitter. I am always captivated by the edge of its collar, seemingly drawn in a single undulating brushstroke of varying thickness.

A couple of years ago, the Met curator Keith Christiansen discovered a “new” work by Velázquez right under his nose. This is the Portrait of a Man (around 1650), which is included in all the catalogues of Velázquez's work, sometimes attributed to the master, sometimes to a follower. He decided to ask Michael Gallagher to see what was beneath a layer of varnish so discolored as to make the picture look green. Lo and behold, it was a Velázquez! (Information about the provenance, date and attribution are contained in a small publication titled Velázquez Rediscovered, published by the Met in 2009, to which I contributed an essay.)

The inclusion of Peasant Girl (around 1645-50) affords me the chance to revisit a problematic attribution. The painting first surfaced in 1972 in Switzerland, the parking lot for paintings with disputed attributions. Wildenstein acquired it in 1972 and then it sold it to a Japanese collector in 1983. In 2000, it was back in Switzerland; four years later, in France. I finally saw it in 2004, when it was in the Conservation Studio of the Prado. By coincidence, a painting then called the Pope’s Barber was also in residence. The latter was done in Rome in 1649-50, the date ascribed to the Peasant Girl. To my eyes, the Girl did not resemble this or any of the paintings executed by Velázquez in Rome. I published my views in the Madrid daily ABC on 21 February 2004 and it not the best idea I ever had. One senior Spanish colleague was so infuriated by my opinion that he immediately wrote a letter to the editor accusing me of blindness.

It was known that a painting of this subject was owned by a famous Spanish collector, Gaspar de Haro, Marquis of Carpio and Viceroy in Naples from 1683-87. Upon his death, inventories of his possessions in Naples were drafted. The proponents of the attribution identified the Peasant Girl with a painting owned by Don Gaspar; the entry refers to the work as a “young woman, with a cloth on her head, bust length.” No artist is named. However, I noticed that a painting similarly described was in the nobleman’s Madrid palace in 1651 and remained there until his death. I believed that Haro owned two versions of the subject, although it was impossible to know which corresponded to the Peasant Girl then on the market.

My theory almost immediately was blown out of the water. A Spanish art historian discovered documents pertaining to the portions of Haro’s estate still in Naples in 1687. To settle the estate, 330 paintings were allocated to a Florentine banker who had lent money to the Viceroy. One of these is described as a “Young Woman, half length, by Diogo Velasco (sic).” This information seems to leave little room to doubt that the Carpio painting in Naples and the Peasant Girl are one and the same and that the Madrid version is lost.

Yet this tidy package of data unfortunately neglects to consider the attribution from a formal point of view. One of the justifications for loan exhibitions is that they provide the opportunity to compare works from various collections. This small show is a mano-a-mano between the Peasant Girl and two other works in the exhibition—the Portrait of Cardinal Massimi, on the one hand, and, on the other, the Portrait of a Man, attributed to a follower. The comparison to the Cardinal is a no-brainer. The Cardinal is a miracle of Velázquez's transparent, economical technique. The execution of the Peasant Girl is clumsy. The roseate complexion of the cheeks is one problem. More telling is the treatment of the white shawl, with its thick, aimless facture, exactly the opposite of the sublime, transparent collar worn by Cardinal Massimi. The brushstrokes float above the surface like wet noodles. Many of these observations could be applied to the anonymous Portrait of a Man. This is a very fine painting, even if the attribution to Velázquez has never been secure. The thought occurs that these two paintings—the Peasant Girl and the anonymous Portrait of a Man—are by the same hand. But if not by Velázquez, then by whom? At the risk of seeming loco, I propose that they are the works of Juan de Pareja; yes, Juan de Pareja, Velázquez's slave, and later assistant. He was a very good painter, to judge from the small number of works attributed to him. They are within Velázquez's orbit, but fall just short of his characteristic manner.

Nothing is more subjective than the attribution of a painting and nothing is more essential than the debate over authorship. Therefore, I invite readers to take advantage of this opportunity and direct their footsteps to gallery 610, where they may draw their own conclusions.

Jonathan Brown is the Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor of Fine Arts at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

Velázquez Portraits: Truth in Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 12 March