David Hockney may be Britain’s most popular living artist—Tate Britain ticket sales have already gone through the roof—but, as this lucidly curated survey is at pains to point out, right from the start he has also been relentlessly experimental in his attempt to represent reality in two dimensions. And at the same time, he has also been dedicated to challenging and interrogating conventions of art making.

This point is forcibly made in the career-spanning first room that shows Hockney mustering a battery of styles and techniques as he strives to capture the experience of being in the world—and in the process putting us at the centre of his world. One painting, of a naturalistic figure seated behind what looks like a pile of spare parts from a Cézanne or a Léger painting, is even called Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965).

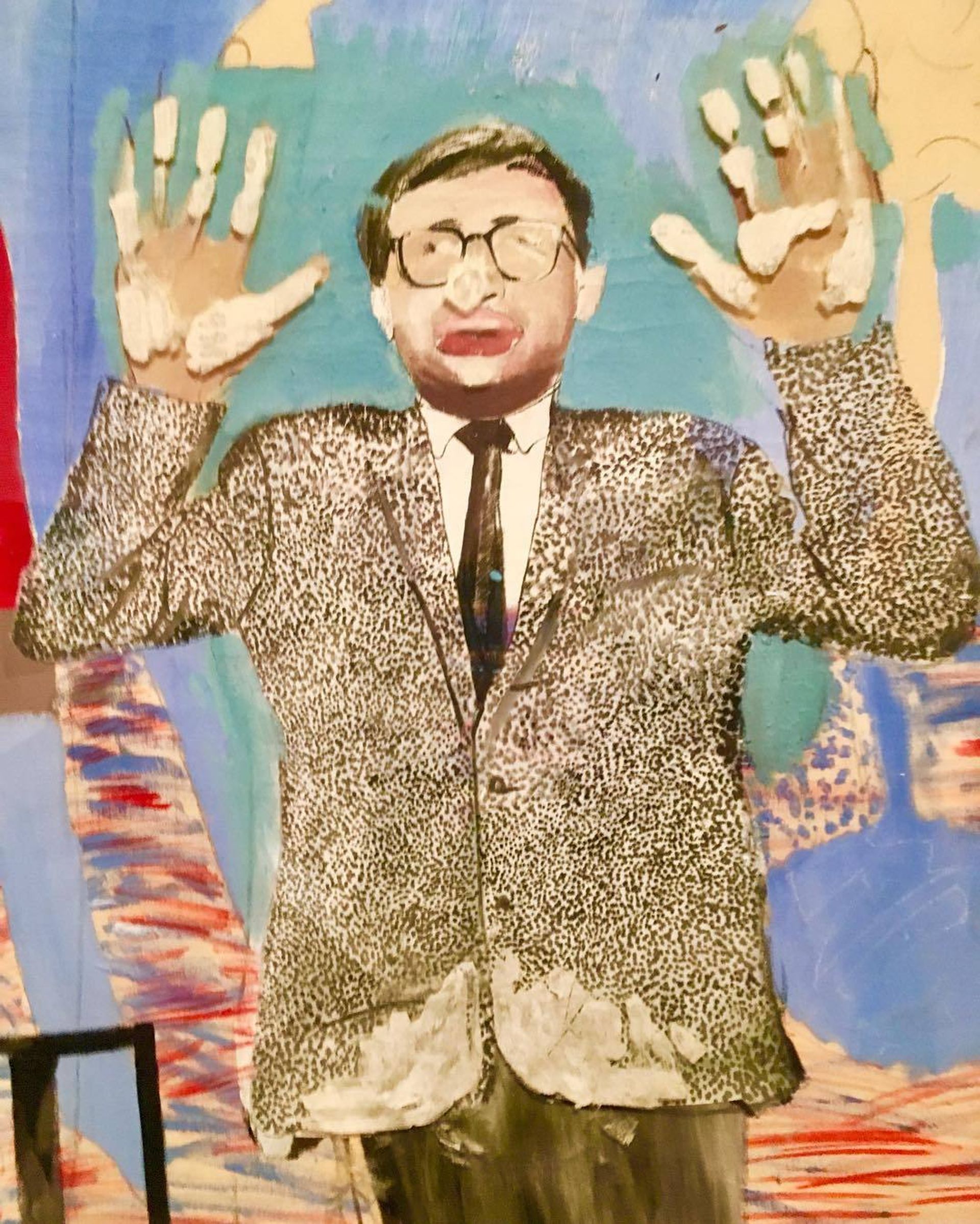

There is an abundance of style-switching and perspectival tricks in Play Within a Play (1963), which also hangs in the first room. A highly playful exercise in reality and illusion, we are eyeballed by Hockney’s dealer Paul Kasmin, who is seemingly squashed up against a sheet of real Perspex, with his pressed nose and hands conjured up in smudgy paint-prints. Behind Kasmin, hangs a tasselled curtain backdrop that is decorated with a lollypop tree and schematic figures.

Thanks to Hockney’s virtuoso skill in handling colour, form and composition, these multi-layered representational riffs hang together and coalesce into rich and engaging works in their own right. An early encounter with the Tate’s 1960 Picasso retrospective was a major influence in liberating his proliferation of styles. Hockney even said: “I deliberately set out to prove I could do four entirely different sorts of picture like Picasso.”

The exuberant room of works painted whilst studying at the Royal College of Art are daring in both form and content, as Hockney samples and combines incongruous styles—scratchy Francis Bacon, scribbled Alan Davie, Jean Dubuffet’s art brut and scrawled graffiti—whilst flamboyantly proclaiming his own homosexuality. There is cruising, coupling and dancing the cha-cha. In Cleaning Teeth, Early Evening (10PM) W11 (1962), a cartoonish pair of hideous, sack-like figures—one chained to the bed—have mutual oral sex, their penises replaced by squirting tubes of Colgate toothpaste and a tube of Vaseline peeping from beneath the bed. Particularly brave, given that homosexual acts were not decriminalized in England until 1967.

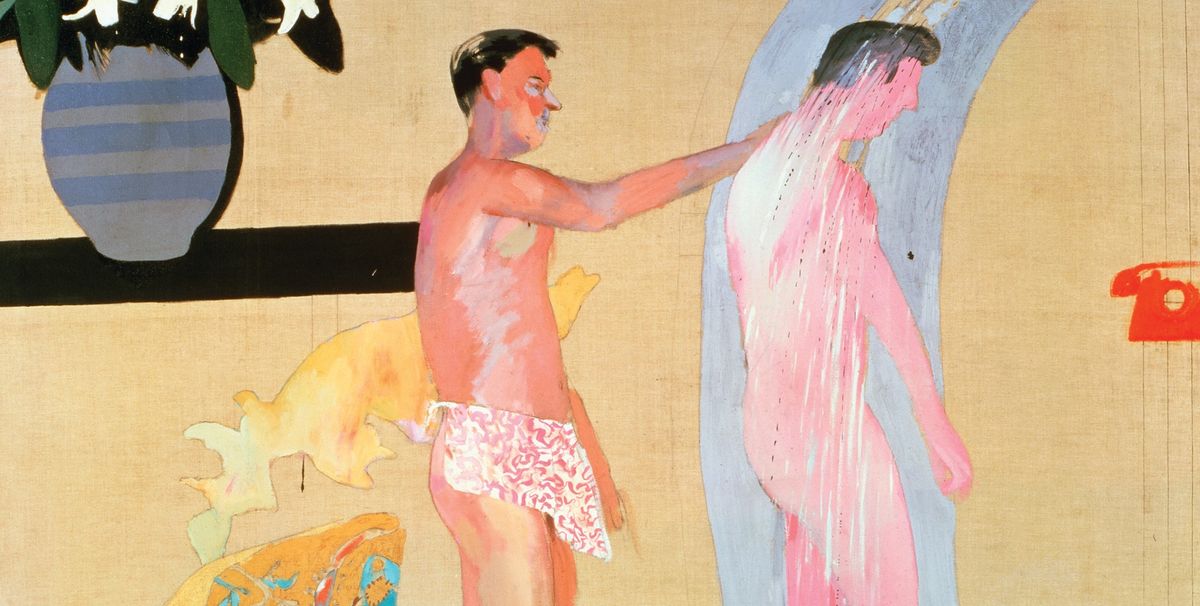

Hockney’s move from the gritty prudishness of austerity Britain, to sunny and sexy Los Angeles is amply represented here in an outpouring of the brilliantly hedonistic painted swimming pools, sprinklers and boys-on-beds or in showers that have become his trademark. Whether in the snaking linear ripples of the pool in Sunbather (1966) or the expressive painterly ejaculation of A Bigger Splash (1967), these good-life paintings also continue to pull between figuration and abstraction.

We then see his style become more naturalistic, but also increasingly restrained, with bodies lightly modelled in clear, uniform light. One of the show’s great galleries brings together Hockney’s grand, near life-sized double portraits painted in quick-drying acrylic, where the subjects seem almost frozen in their empty, immaculately composed surroundings. But at the same time, all manner of intimate and complicated relationships simmer beneath their apparently dispassionate surfaces. The US collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman are punctuated by, and appear indistinguishable from, their sculptures. While Christopher Isherwood turns and gazes ferociously at Don Bachardy who stares blithely straight ahead, the empty space between their matching armchairs filled by a bowl of suggestively positioned fruit and a lone phallic corncob.

Drawing has underpinned all of Hockney’s art and one of the highlights of this show is the densely-hung gallery devoted to drawings from the very beginning of his 60-year career, with a particular emphasis on the glory years of the 1960-70s. In the earliest work of the entire exhibition, the 17-year-old Bradford School of Art student—specs already in place—fixes you with a steady gaze as he adjusts his tie. This modest, pencil self-portrait ushers in a glorious parade of works in all styles and modes: another smudged ink boy in cap entitled Fuck (Cunt) (1961) and the coloured pencil drawings of stage sets, boulevards, seated friends and Beirut hotels. There is a vivid, washy-watercolour landscape of mountains and trees in Kweilin, China, painted in 1981 and—my particular favourite—a series of delicately intimate yet restrained ink portraits. These range from Peter Langan surrounded by kitchenware in his Odins restaurant, to a decidedly morose Peter Schlesinger (Peter Feeling Not Too Good, 1967) and WH Auden, smoking a cigarette and looking like an Easter Island statue.

It is in his intense and highly personal observation that Hockney’s greatest work is to be found. The more he attempts to extend his modus operandi via mechanical means, the more he complicates and ultimately dilutes his formidable powers of expression. This is ominously signalled back in the first room in which the unfortunate addition of the more recent digital print 4 Blue Stools (2014) suggests that his exuberant spatial and stylistic experiments of the 1960-70s, evolved into a dry and uninteresting plotting and pasting-in of photographic figures, furniture and reproductions of past paintings into an evidently artificial space.

Try as it may to laud Hockney’s relentless desire to render multiple viewpoints—both psychological and optical—by using the latest in new technology, Tate Britain’s survey confirms that the resulting works have not been amongst his best. The forays into photography, whether the composite polaroid portraits of the 1980s or the multiple-viewpoint vistas, are interesting and accomplished but nothing more.

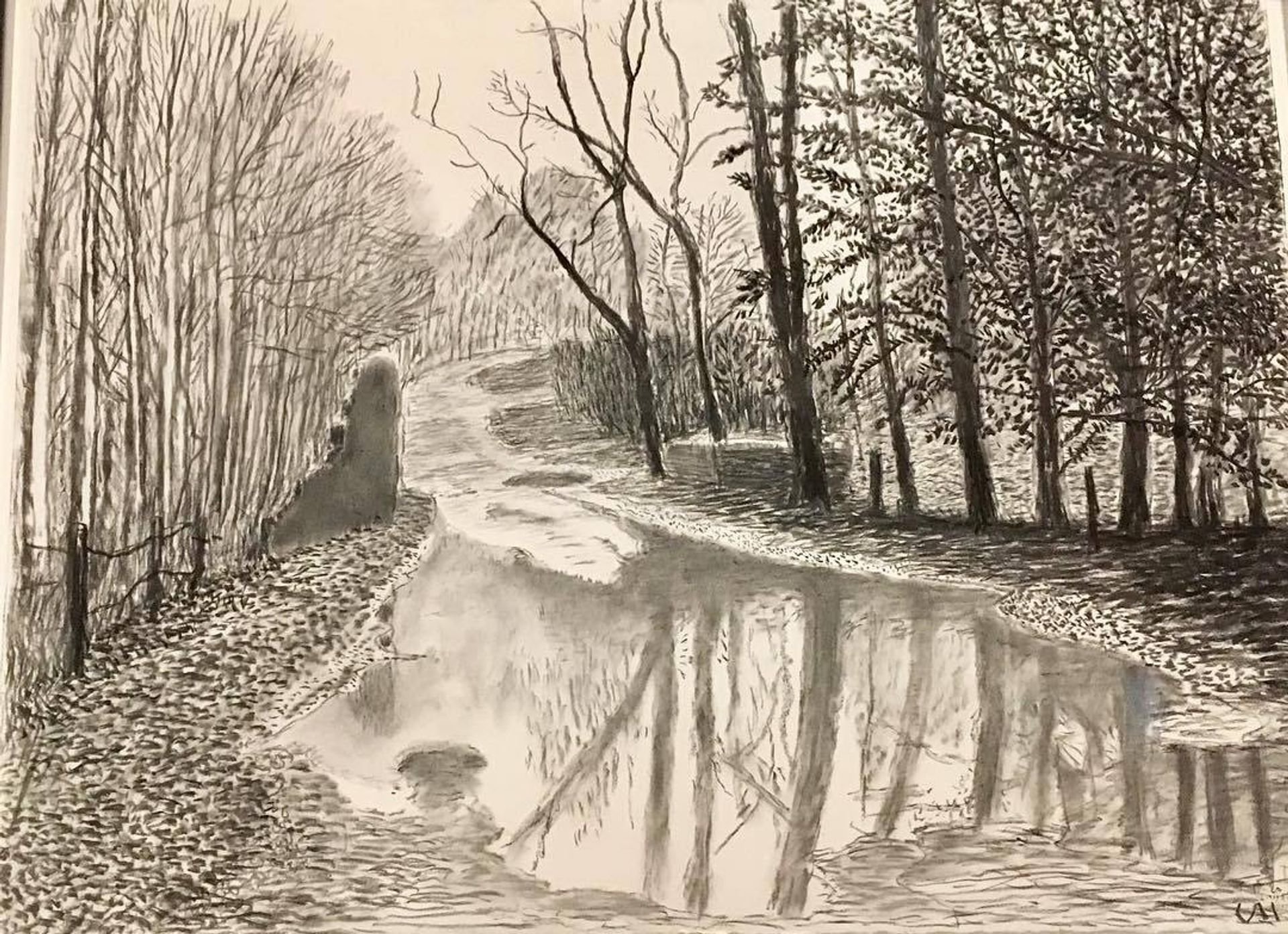

This also applies to the quartet of films on multiple video screens that depict a slow progression along the same stretch of country road near his East Yorkshire home during each of the four seasons. The high definition progression through the leafy lane of Woldgate Woods simultaneously in unfurling bud, full leaf, fall and snow, makes for a relaxing and highly pleasurable immersion in the glories of nature. But an infinitely more intense and evocative sense of place, light and atmosphere is given by the 25 charcoal drawings depicting the arrival of spring along a nearby lane, which Hockney made in 2013 before returning to live in the Hollywood Hills.

Despite the last room of the exhibition being vividly, alluringly alight with Hockney’s unfolding quick-fire drawings on his iPad, it is the quiet assiduously observed monochrome charcoal studies of texture, reflection and shadow that have stayed with me.

• David Hockney, Tate Britain, London, 9 February-29 May