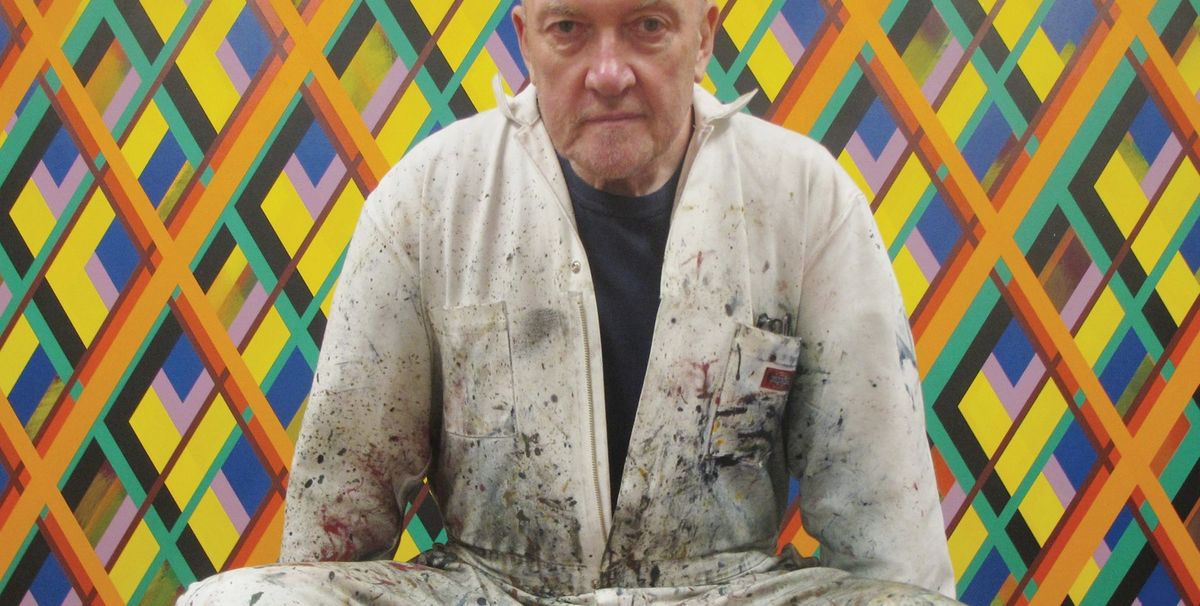

The Irish-American artist Sean Scully has found a receptive audience in China, especially in its art schools. The Hubei Museum of Art in Wuhan last month opened the final leg of a career survey Resistance and Persistence (until 12 March)—his second in the country in just over two years. Scully’s first solo exhibition in China, Follow the Heart, opened at the Shanghai Himalayas Art Museum in late 2014, and then travelled to the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

His second solo exhibition in China includes around 60 works made between 1967 and 2015. It has already been to the Art Museum of the Nanjing University of the Arts and the Guangdong Museum of Art. Ahead of the opening in Wuhan, which included a book signing for a Chinese translation of Scully’s writing, we spoke to the artist about China and its appreciation of his abstract paintings and the ideas behind them.

The Art Newspaper: What do they like about your work in China?

Sean Scully: They like the way I am. They respond to me tremendously as a person. And I think they like the work because it’s connected to the real and it’s very metaphorical. They read the metaphors perfectly, and in certain ways my work is emphatically clear. It’s not a mystery. You can’t misunderstand it, in a certain way, because it is so based on reality. The metaphors I use in [the titles of series such as] Wall of Light and Landline are very tangible. They make abstraction real for people.

Do they see your work as something they already know, or something new they can still admire?

It might be a little of both. They’re a very literary people and they’re very widely read, so they understand the references I make in works such as Pale Fire [1988, named after Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel]. What they see in my work is a kind of abstractness that is emotionally based and they see that as very authentic. I also think they have, in their own cultural language, a very high degree of abstraction.

Because it’s such a technological society, they’ve had other kinds of work before abstraction. They’ve got some fantastic photographers and video artists and performance artists, and now they’ve worked their way back to painting.

In the West, we did it other way around, but of course now we’ve come back to abstraction.

Can you see the influence of your work already developing?

Yes. After my show at the Chinese Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, they opened—if you can believe this—as an homage to me, a department of abstract painting at the school. I’m in all these readings they put out for the students—and I was before I came here. The art schools in China run everything. In that sense, it’s a lot like England.

Are there private and public collections buying your work?

The Shanghai Himalayas Museum bought two and I donated a couple of others: one to the Chinese Academy of Fine Arts and one to the Museum of the Nanjing University of the Arts. And there are some private people buying my work.

But what you have to understand about China is that it’s not a market; it’s an intellectual exercise. Somebody likened it to New York in the 1950s. That’s what it’s like. The way to go to China is to have an intellectual discourse, a cultural discourse. That’s what they’re interested in. It’s not like they have this rampant market. It’s a market that’s active up to $100,000, and of course I’m above that. For people at my end of the market, it’s really limited. It’s not developed at all yet. But what has developed is the intellectual basis for all this, which comes out of the art academies, which are very interesting places, where people develop interesting concepts and an incredible degree of technical ability.

Is it a difficult country to navigate?

It’s very different from what you think. It’s kind of like the Wild West and the driving is a bit like the driving in Italy. They cut in front of each other, they don’t follow the rules. If you’re on a one-way street, there are motorbikes going the other way with people talking on iPhones. So you have this kind of rural psychology with high-tech equipment—it’s the strangest thing.

Is there anything else on the horizon in China?

No, this is the grand finale for now. I might leave it for a decade because this is five big venues for two full-blown retrospectives. So I think that we’ve done it for a while and the impact will be tremendous. Apart from that, I’m doing stuff in America, including a show at the Hirshhorn [Museum and Sculpture Garden, in Washington, DC] and at the Cheim & Read gallery [New York].

• Sean Scully: Landlines, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 8 June-1 October

• Sean Scully, Cheim & Read, New York, 30 March-6 May