Keeping Their Marbles

Tiffany Jenkins

Oxford University Press, 384pp, £25, $34.95 (hb)

The acquisition of art, if not its creation, has always followed political and financial power, not to mention martial conflict and energetic exploration and appropriation. This is a forthright, strongly worded essay about issues surrounding the public collections of artefacts culled from all over the world and now held in public museums and galleries.

The material that is the focus of the author’s attention has mostly been acquired by potentially dubious means, questionable legality, coercion, force or just plain looting. The methods by which material, from the realms of both science and art, ends up in the public domain are legion. Along the way we are given a potted but vivid history of the public museum.

For example, some 900 Benin works of art were taken by the British when they destroyed the kingdom of Benin at the end of the 19th century and are now held in five different countries, including Nigeria. Should such surviving material fragments, which have been shifted by currently questionable means, be returned to whence they came, and if so, returned to whom? Or what, as this book so eloquently and determinedly argues, are the overwhelming reasons to keep what we have? To my knowledge, one great museum director of a great British museum simply beamed when asked about repatriation; his reply was that the art was owned by the museum, end of story.

One scholarly outcome has been that provenance is crucial, providing footnotes to the vexed questions of exploitation, empire, conflict and colonialism that shadow great collections as they shadow human history. Legality vies with differing views of morality and ethics.

The author produces scores, even hundreds, of contested examples, particularly vexed when the objects have sacred meanings and in themselves are objects of veneration and worship. Her conclusion is staggeringly firm: “The mission of museums should be to acquire, conserve, research and display their collections to all. That is all and that is enough.” Jenkins exhibits an unfashionable determination to eloquently argue that what we have, we hold.

But just wait: for it is only a matter of time until China begins to initiate official requests for the return of the many objects that were looted from the Summer Palace in 1860 by the French and the British in the Second Opium War. Not up for repatriation is the Empress’ dog, Looty, a Pekinese, which was, believe it or not, presented to Queen Victoria. His portrait is in the Royal Collection.

• Marina Vaizey is a freelance lecturer and writer. She was the art critic of the Financial Times and subsequently the Sunday Times. She currently writes for theartsdesk.com

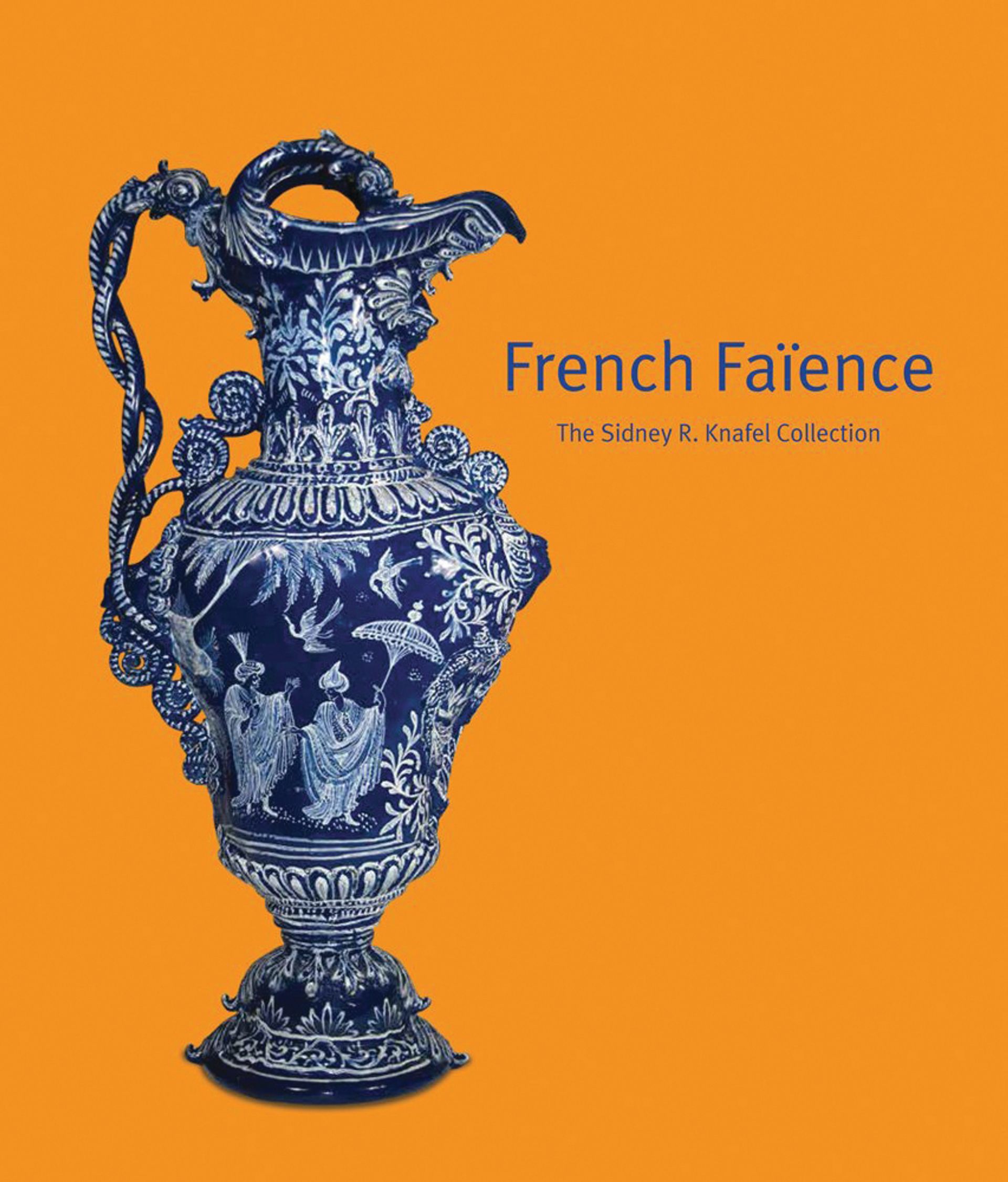

French Faïence: the Sidney R. Knafel Collection

Sidney Knafel

Mare & Martin, 352pp, $40 (hb)

“Let us praise, daughter in Heaven, the honour of faïence. What an art! It was created in Italy and came over the mountains to Nevers; its charming works of art go beyond the Seas.” Pierre de Fresnay’s poem in praise of French faïence, published in the Mercure de France in 1735, promotes an art form that was once popular with collectors in France, but which has largely fallen out of fashion. It evokes the collection formed in New York by Sidney R. Knafel over the past 50 years, which is dedicated to French faïence (tin-glazed ceramics) made in France from the 16th to the 18th centuries, as French workshops took up the tradition of pictorial pottery from Renaissance Italy and adapted it into a national art form.

This book, with its large colour illustrations, is not merely beautiful, for in describing one of the best collections of its kind in private hands it makes a serious contribution to the subject. William Bowyer Honey, formerly Keeper of Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, praised French faïence for its “incomparable measured grace” and claimed it to be “sympathetic and civilised and characteristically French”. Looking at the treasures here, it's hard to disagree: the superb series of pieces from Nevers and Rouen alone would justify his judgement.

The book, however, covers a much larger and little-known production from Lyons, Marseilles, Moustiers, Sinceny, Saint-Omer, Lille and Montpellier, with rare and excellent examples in each category. The text is bilingual in French and English, with a short preface by the collector and an introduction by Charlotte Vignon from the Frick Collection. It is not a catalogue, but contains contributions from some of the greatest experts in the field of French ceramics, edited by the dealer Christopher Perlès. The entries on Nevers, for example, are written by Camille Leprince and present new attributions to the painter Denis Lefebvre and to the Conrade workshop among the signed and dated pieces in the collection.

Particularly significant is a large oval moulded dish of around 1630-50 which is decorated in blue with scenes from the Old Testament after Bernard Salomon. In its form and decoration it confirms the relationship between Nevers production and the best Italian maiolica made in Urbino.

Details of signatures and print sources add to the charm and usefulness of a book that deserves a wide readership.

• Dora Thornton is the curator of Renaissance Europe at the British Museum, London, and the author, with Timothy Wilson, of Italian Renaissance Ceramics: Catalogue of the British Museum Collection (2009)

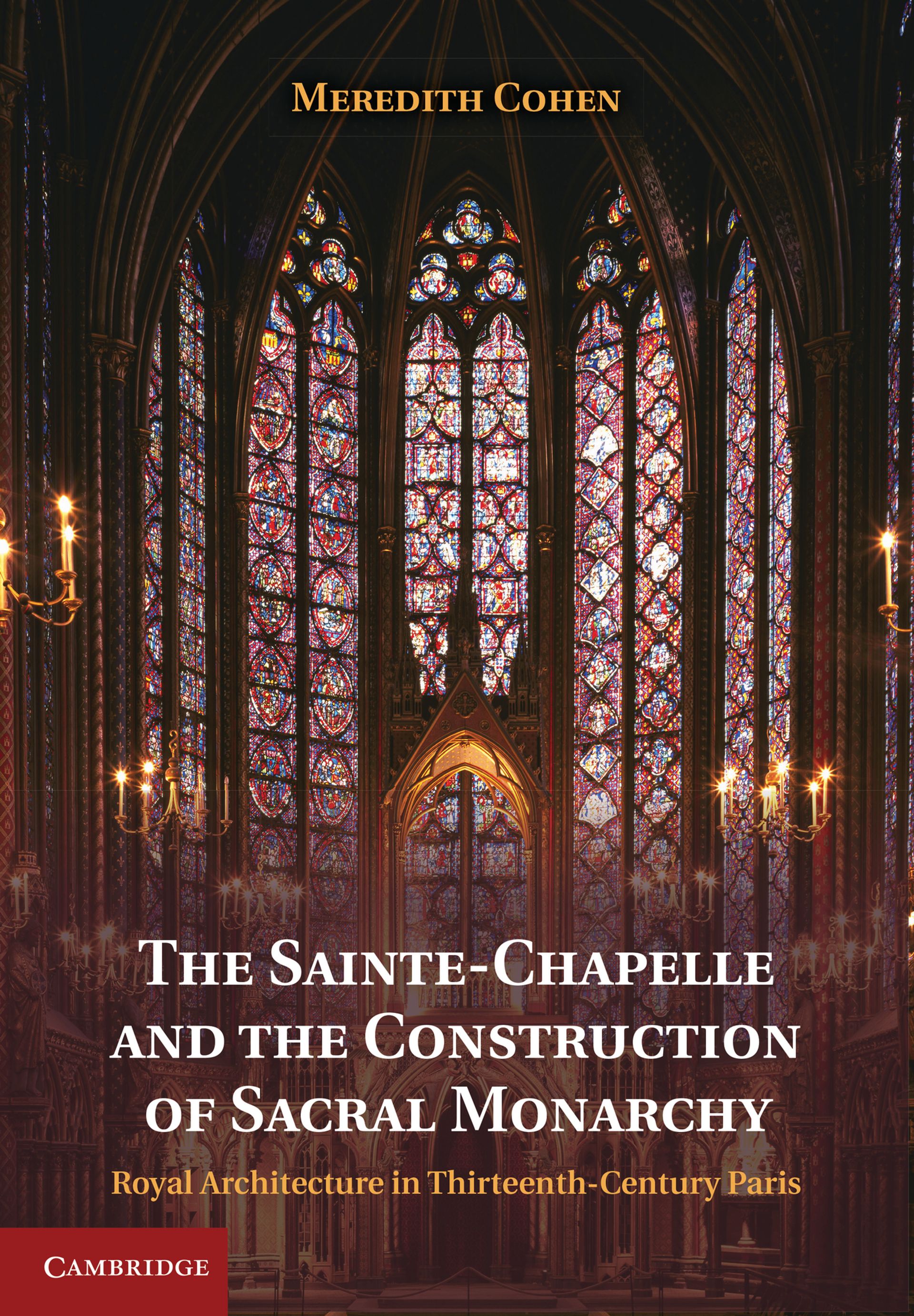

The Sainte-Chapelle and the Construction of Sacral Monarchy: Royal Architecture in 13th-Century Paris

Meredith Cohen

Cambridge University Press,

400pp, £75, $120 (hb)

As the subtitle implies, although the Sainte-Chapelle is at the heart of this volume, the author ranges more widely, both temporally and spatially. The first chapter is devoted to the building works of Philip Augustus at the start of the 13th century, credited here with no less than a transformation of the city. Detailed and often highly technical discussion of building styles is backed up with lavish illustrations, as is also the case when the author turns to the building programme of Louis IX and to the Sainte-Chapelle itself in the second chapter.

It is the second element of the title, though, which is explicitly offered as a “novel perspective”, and here Meredith Cohen is less assured and correspondingly less persuasive. “Construction” echoes the earlier discussion of building works, but in so doing it implies a conscious act of creation. Louis IX must indeed have known very well what he was doing when he acquired the relics of Christ’s Passion and built the Sainte-Chapelle to house them, but the idea of the king as the Lord’s anointed–literally so through the unction of the coronation ritual–is considerably older, as the author concedes. What was contested was the power this gave him vis à vis the Church, and that was an argument that was not going to go away, even if Louis was now acknowledged as the Most Christian King.

Certainly the Sainte-Chapelle was sending out a very strong message, but who was the intended recipient? Cohen insists on its broad appeal “from the international élite to the poorest inhabitants of the city”, but it seems unlikely that the poor made it inside other than on Maundy Thursday when a group of them were rounded up to have their feet washed. And what drew the crowds were the relics themselves, which were regularly processed round the city and were heavily indulgenced.

Louis’ acquisition of them had been a staggering (and expensive) coup, which no other European ruler could rival. That said, the chapel itself was also an undoubted tour de force. Henry III, who was in Paris in 1254, coveted the building and was said to have wanted it transported on a cart from the Seine to the banks of the Thames. His rebuilding of Westminster Abbey was to be his own answer to Louis’ creation. So, much less successfully, was his acquisition of the Holy Blood, which never aroused the fervour that Louis’ collection generated.

Royal courts are emulous places, and Louis IX had definitely emerged the winner in this particular competition. But the successful manipulation of soft power, however impressive, does not amount to a refashioning of the nature of monarchy along the lines suggested by the author. In the personal monarchies of the Middle Ages, any sort of sustained linear progression in the ideology of kingship is inherently unlikely, and indeed Louis on his return from crusade was to cut a rather different figure. The beauty of the Sainte-Chapelle and the power of its relics are very well explored here. The claim that “this architecture effected changes in social patterns and thought” proves harder to sustain.

• Rosemary Horrox is a fellow of Fitzwilliam College, the University of Cambridge, and has published widely on late Medieval political culture and society, including the Black Death