Anyone desperate to find hope and humour in a country run by little men with big egos would do well to look at the art of Tehran-born, Los Angeles-based artist Tala Madani. Through her paintings, and also short stop-motion animations, she has a history of exposing the absurdities of a hyper-masculine and at times savagely phallic culture. Her speciality is depicting—with an economy of brush strokes—sad-sack, naked, misshapen, balding, middle-aged men who excrete, secrete and play with themselves like strange, overgrown babies.

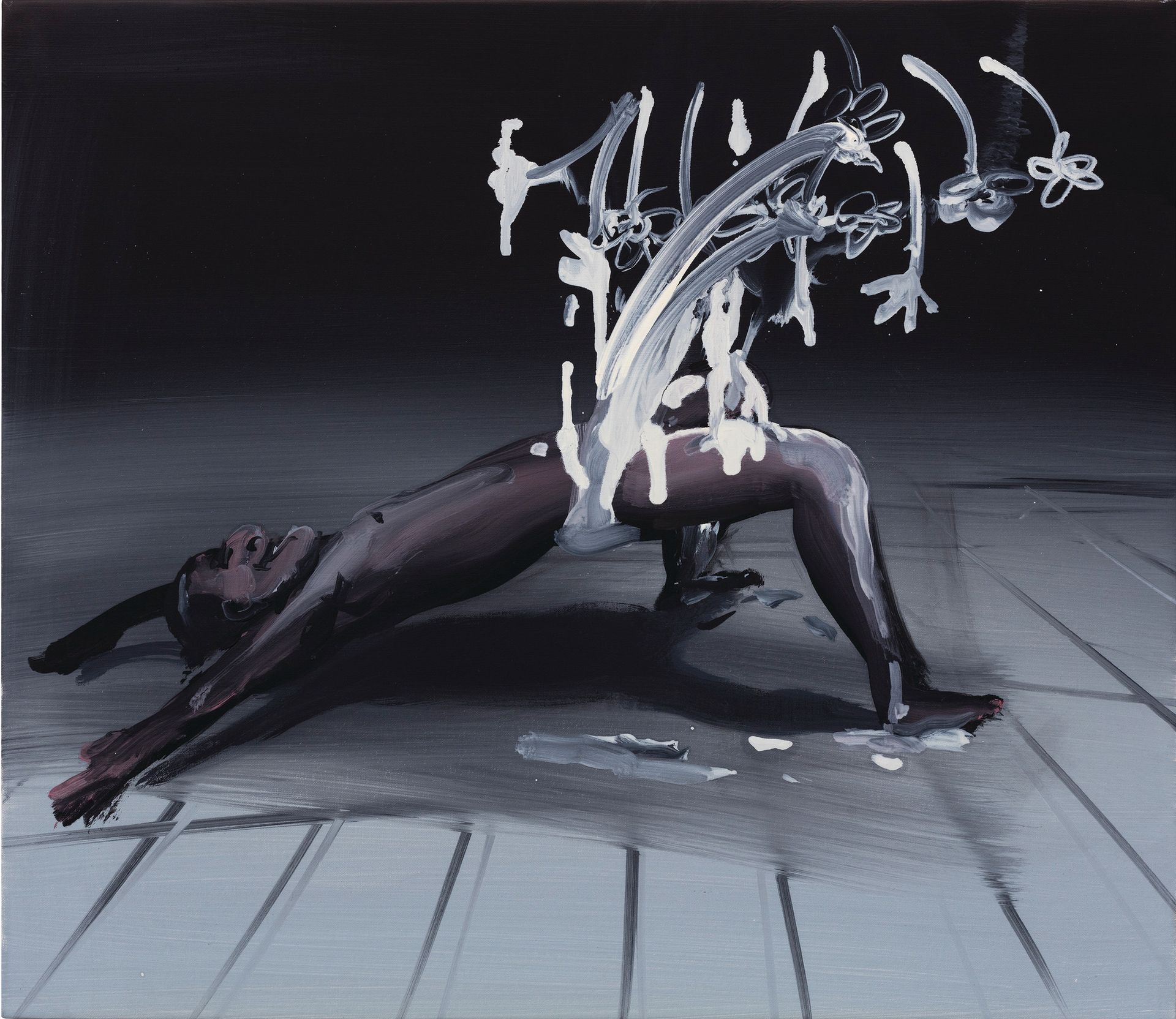

In one painting, a man reaches into his anus and pulls out his intestines. In another, a man with a dreamy closed-mouth smile and closed eyes pulls his unnaturally long fire hose of a penis over his shoulder, stroking it like a fur pelt, while white paint gushes out the tip. Women are nowhere to be found. Madani, who has been compared with artists as diverse as Mike Kelley, Philip Guston and Sue Williams for her use of grotesque and cartoonish elements, has found a subject worthy of caricature in the virility fantasies of ageing men.

These days she is finding a broader audience too, from her 2015 show at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, where creepy, smiley-face figures invaded her paintings, to a 2016 show at Pilar Corrias in London, called Shitty Disco. She has had a busy start to the year, with her first solo exhibition in France now on at La Panacée in Montpellier quickly followed by her participation in the Whitney Biennial in March.

The Art Newspaper: The curator Aram Moshayedi wrote an essay that warns us against “racialising” your men. But they really do look Middle Eastern to me: the bushy eyebrows, the jawlines, the noses. Where do you stand on this?

Tala Madani: There is definitely a choice in the way I make them look. I’ve made so many paintings and I’m not done with them yet. I think they do look Middle Eastern but in the broadest way: Turkish and Arab and Persian and Jewish and potentially Russian and Georgian and even slightly Greek. It’s important to recognise that, as someone born in Iran who lived there until I was 15, I am making these paintings from a core place. I’m not going to camouflage them by making them look Germanic or Swedish or Native American. I can’t undo the way my brain images these characters. But at the same time there is a caveat: this man is all men, he is a He. If you only think about him in relation to Iranian politics, you’re missing the point, in a way.

You’ve taken this basic smiley-face image and given it some emotional punch. Where did you get the idea of using a smiley face in your painting?

The smiley face is so culturally specific. It was first developed in the 1960s in the US as an advertising strategy, and then it was co-opted by hippies who were part of the anti-war movement. The smiley face wants to say: peace, happiness, everything is OK. But I started to think about what it doesn’t say, everything that gets left out. What’s really interesting is its minimalism: two dots and one bent line, and that’s all you need to make a smiley face. What is excluded from the smiley face? It’s bald, it has no hair, it has no nose. It’s neutered, if we think of a nose as a phallic symbol.

I love the fact that you show us the source of light within a painting—depicting what looks like a theatrical spotlight on the one hand and an interrogation lamp on the other.

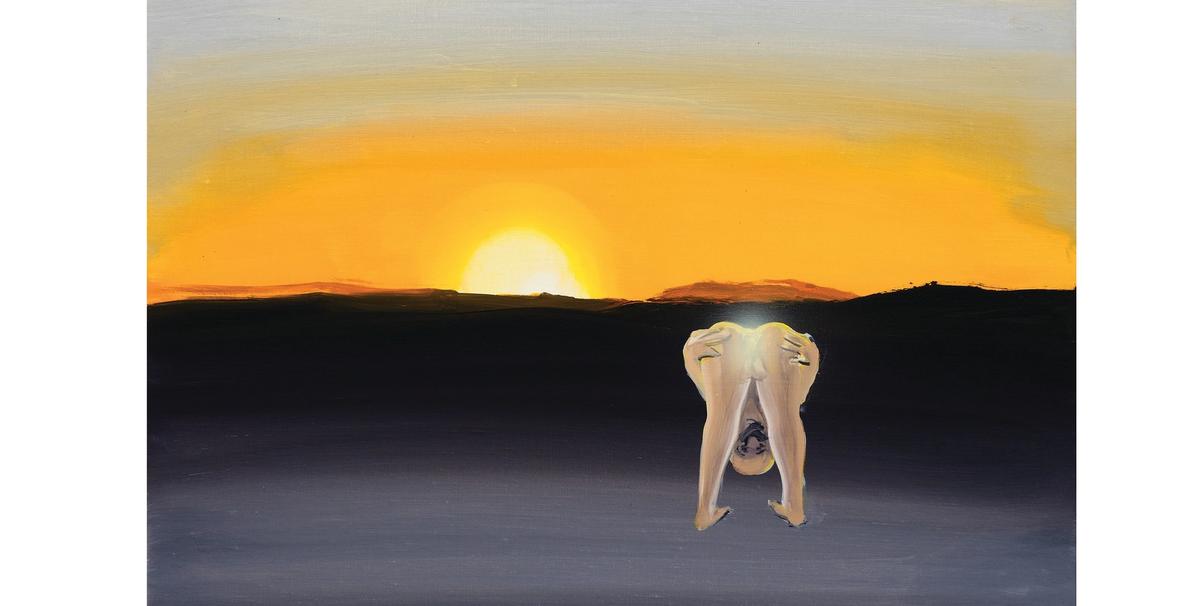

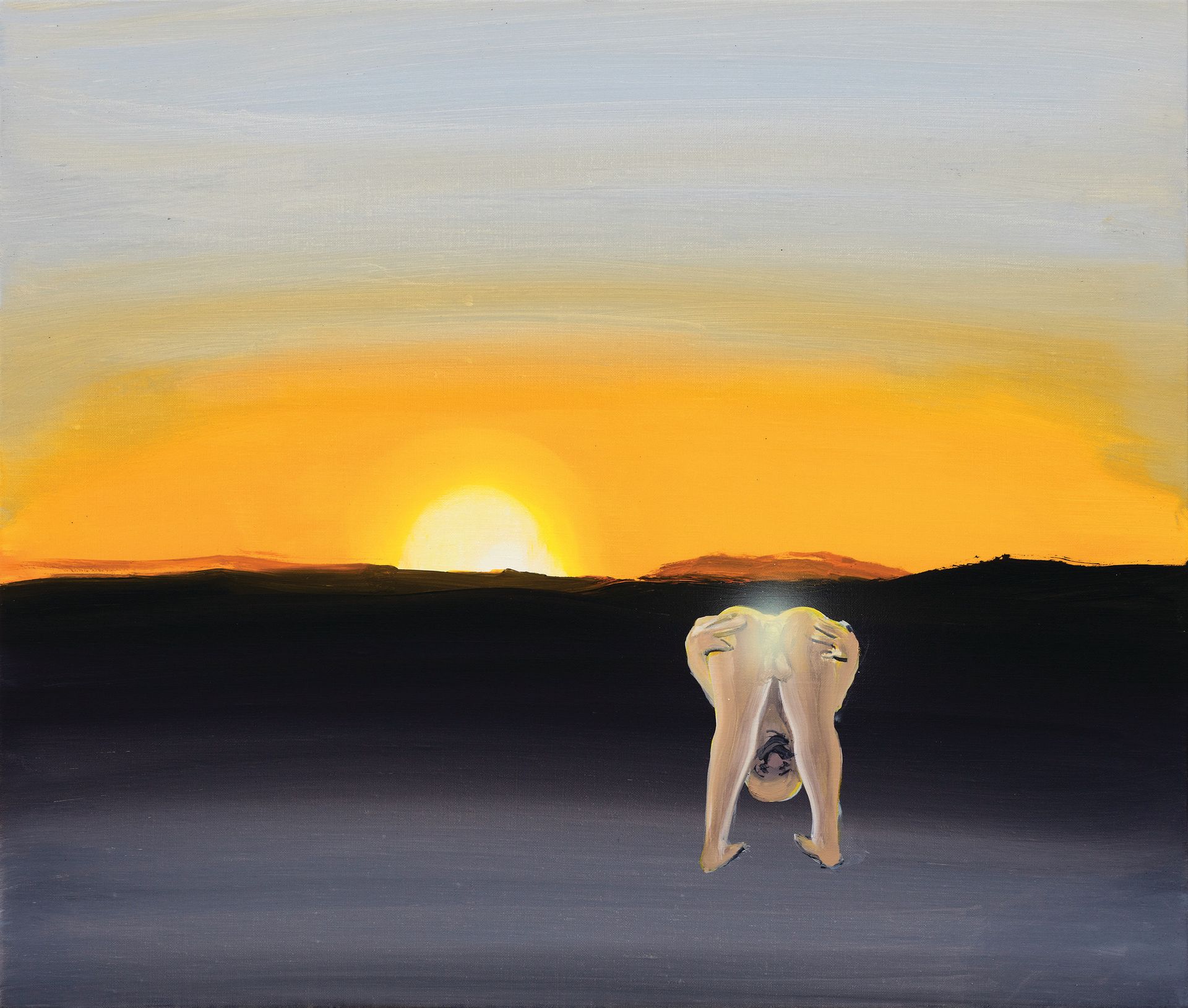

For me, the painting as a square or rectangle always feels like a theatrical space. When I’m working, it feels like the painting is performing—and whenever you put something on a painting, you are giving it a metaphoric spotlight by painting it. I’ve kind of literalised that in my painting, by really giving it a spotlight. In my new work in Shitty Disco, the light is coming from the bodies of the characters. I’ve done that a few times—it’s not entirely new. So here you see disco lights coming from the ass, also shit coming from the ass, which I think is a reaction to what we’ve been going through this past year. We are in a shitty disco right now, with Brexit and the election here [in the US].

Your work clearly has cartoonish elements. Are you a fan of particular cartoons or comic books?

Growing up in Iran I used to read this magazine Gol-Agha. It translates as The Flower Man—which is akin to the smiley face, now that I think of it. It’s a satirical magazine, for adults, not kids. That was a very big influence subconsciously. But in a way my paintings grew closer to comics not because I was so interested in them but because I’m interested in accessing what is childlike in me myself. I’m interested in a kind of figuration that’s not about precision but about trying to catch the ideas of your brain. I wanted to paint at the speed I was thinking, and that led to a shorthand or notational way of working.

What can you tell us about the work you’ll have in the Whitney?

I’ll have five paintings and hopefully one animated film—I’m finishing that now. Two of the paintings were part of Shitty Disco. It’s all work from the past six months, and it deals with this idea of a missing maternal energy. I’ve played with the idea in some earlier paintings, but it’s a little more focused now. I’m adding a child character and some female elements that pull out what’s lacking more.

You have a young daughter, just over a year old. Has it changed your work?

I think so. I’ve been interested in painting children, but children are very different to grown people in terms of proportions. So now that I’ve been staring at my child for a year, I’m getting better at it. And when I went to the studio again, I became so aware of tactility in painting. Babies put such light pressure on objects before they learn how to put more pressure on things. I was thinking about her touch, the way she touches the piano or my skin, and how it’s changing. At first she played piano so softly and now it’s like bang, bang. I started experimenting in the way she was experimenting—applying way lighter and way heavier pressure with my paint rag or brush. This was totally unexpected for me.

When I look at some of the men in your paintings, they remind me of Donald Trump. Do you see that?

People have told me that the man in one of my paintings, Spiral Suicide, looks like my husband [the artist Nathaniel Mellors] or Peter Halley [the artist who was her dean at Yale] or Donald Trump. But I wasn’t trying for that. I’m turned on at some level when I’m painting, and painting particular people kills it for me.

• Tala Madani, La Panacée, Montpellier, France, until 23 April; Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 17 March-11 June