Anyone driving up the A1 towards Gateshead in the North East of England cannot fail to notice the 20m-tall figure of the Angel of the North, which has become an emblem for the whole region since it was created by Antony Gormley in 1998.

This year, the bicentenary of the birth of George Frederick Watts, probably the best English artist we have nearly forgotten, the South of England will also get a totem work of art, to be sited near the A3 highway leading to Guildford and then London.

Many people know the sculpture already. It is the straining, stamping horse with its naked horseman who shields his eyes as he stares into the far distance that they see if they walk through Kensington Gardens in London. But they may well not know who it is by and that it was so famous that the British government, which was notoriously mean in those days so far as artistic matters were concerned, financed its casting after Watts’s death in 1904 and installed it in the park in 1907. The first cast was made in 1902 and is in Cape Town, while the second posthumous cast is from 1957, for what is now Harare.

Watts lived up to Michelangelo’s dictum, “There is but one art”, and, although he was best known as a painter, he began his artistic life as a pupil of the sculptor William Behnes, when he was only ten years old. The Parthenon Marbles were a major inspiration and he also imagined a kind of archaic style that he thought the most famous Greek sculptor, Phidias, would have used on his vast sculptures such the Athene in the Parthenon, but since none of these survives, we cannot know whether he was right or not.

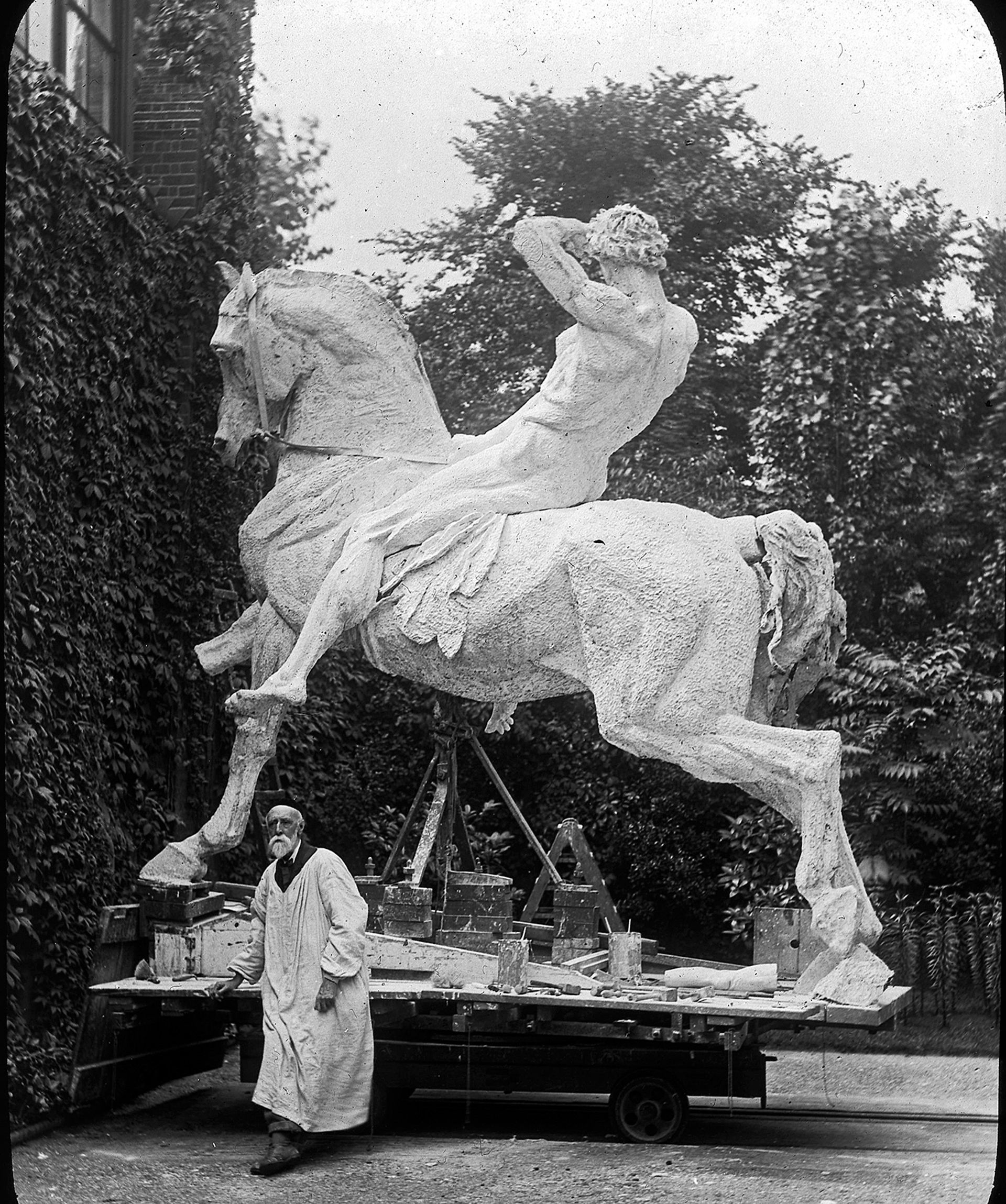

Watts started on the horse and rider in 1884 and they became the companions of his later life, on which he was still working shortly before his death. He would have the four-metre high model trundled out of his studio to chisel away at the stone-hard mixture of rough plaster, glue and chopped hemp (gesso grosso) built up on a wooden framework, occasionally adding new plaster and filing it down.

These processes account for the sculpture’s rough texture, to which he could have given a smooth finish by covering it with layers of fine plaster, but he chose not to because he was not aiming for a precise description of reality. In 1890 he considered having the base inscribed with the names of Genghis Khan, Tamburlaine, Attila and Mohammed, but then he settled on its actual title, Physical Energy, because he wanted the piece to be of universal significance, “to belong to everything—roots and stones and trees and mountain”.

On another occasion, he said that he did not aim to represent reality but ideas, and this is what makes Physical Energy so radical, much closer to ideologically inspired works such as Soviet sculptures at the 1936 World Exhibition than the work of his younger contemporaries such as Alfred Gilbert.

This was understood at the time, and while there was some criticism of the piece’s rough surface, its emblematic power led to a request for it be installed on the site of the 1908 Olympic Games. “Watts was an idealist”, says Antony Gormley, “A pioneer of the modernists who believed in the creation of art that transcended race, creed and language.”

Raised up on a much higher plinth than the one in Kensington Gardens, Physical Energy will be an heroic, eye-catching addition to the Surrey countryside, as well as dramatic marker close to where Watts once lived and worked with his wife Mary. “With a third posthumous cast of this great work as a new landmark for Surrey, I can’t think of a better way to celebrate the region’s most famous artist and the unique artists’ village which Watts bequeathed to today’s visitors”, says Perdita Hunt, director of the Watts Gallery Trust.

The casting, which is from the original plaster model, will be by the Gloucestershire foundry, Pangolin Editions, and it will be complete by this summer. The Trust is in the process of raising the £700,000 necessary, also to landscape the site.