The exhibition John McLaughlin Paintings: Total Abstraction at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) invites us to revisit a moment when abstract art put all reference beyond itself in abeyance. The moment may be a nostalgic fiction.

Reproductions of paintings such as those in the Lacma exhibition catalogue for the show amplify this whisper of idealism more than McLaughlin's paintings do themselves: their handmade look and feel (and in some cases condition problems) humanise his acknowledged obsession with formal control. Viewers can imagine themselves making these paintings (or trying to) as they gauge the aesthetic pressure of making decisions about proportions, colour mass, surface area and the tensions within compositional geometry.

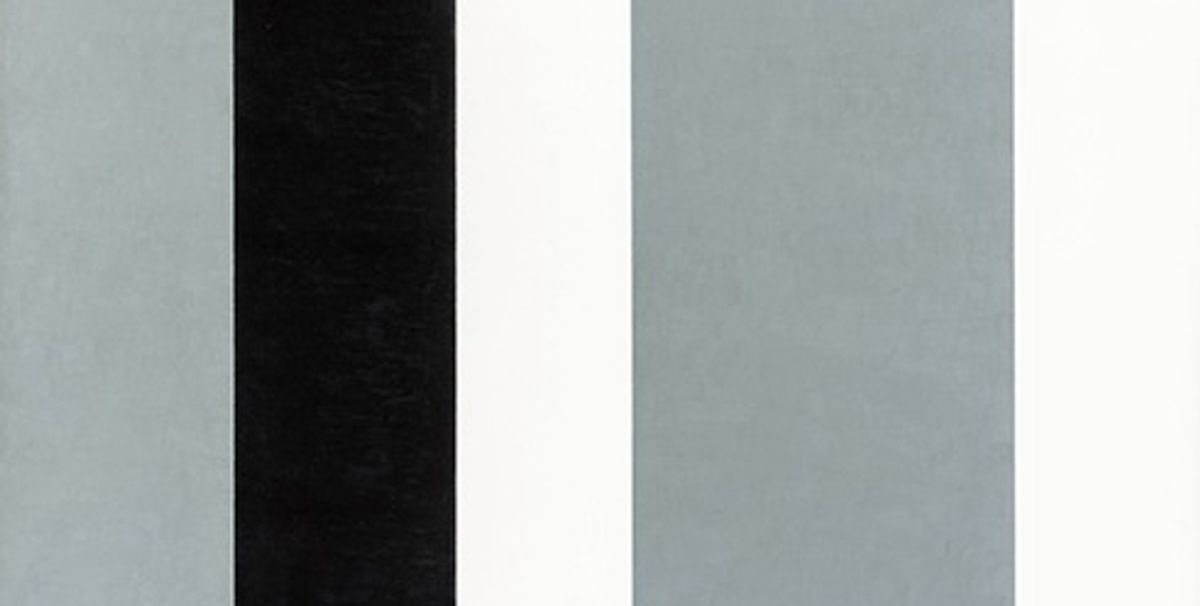

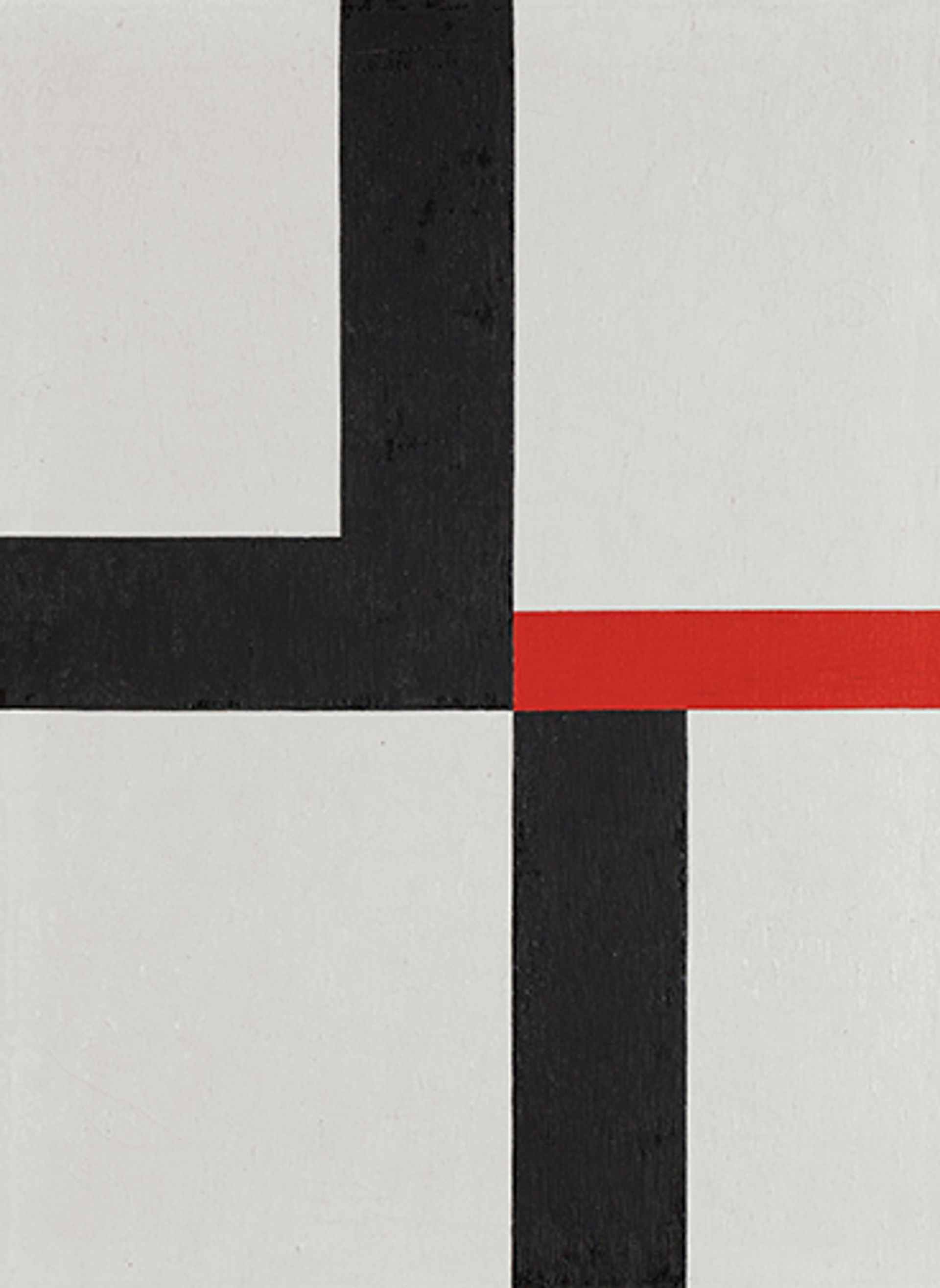

McLaughlin (1898-1976) evidently thought it axiomatic that no form or configuration should appear larger or smaller, optically nearer or more distant, than its physical measure on a picture surface. Nothing should look in any degree scenic or anecdotal. At most—or at worst, he might have said—a properly abstract painting ought to evoke nothing more than another sufficiently abstract work, as his painting #6-1970 calls to mind Kazimir Malevich's Black Square (1915) and V-1957 appears to dream an asperity implied by (but unachieved in) De Stijl.

Critics have found the strictness of McLaughlin's attitudes toward creation and reception reflected in the Southern California art of later generations, from Robert Irwin's and James Turrell's insistence on patient perception to the rigour of abstract form in the painted work of John McCracken and Peter Lodato. But beyond the Los Angeles region, McLaughlin's influence has been more atmospheric than documented. (Inverleith House in Edinbugh gave Europeans their fullest, and nearly its only, view of McLaughlin in 1999.)

To most 21st-century art world insiders, it probably seems as if McLaughlin's art has long been in eclipse, thinly dispersed in public and private collections. Consequently, Lacma's exhibition will come as a revelation to most visitors.

A wider frame of reference reveals in McLaughlin's work a seeming foreshadowing of the art of painters farther afield, such as David Simpson in the Bay Area (especially his rectangle-studded abstractions of the 1980s) and Harvey Quaytman in New York.

The self-taught McLaughlin did much of his mature work while living in relative isolation in small-town, coastal Southern California. But the Massachusetts native had a wide experience of the world.

His youthful familiarity with the great Asian art holdings of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and with the private collections of his relatives primed him for years spent living in Japan and China following his service in World War I. While based in Tokyo, he acquired enough antique Japanese prints to set up as a dealer in Boston in the late 1930s.

McLaughlin's knowledge of the Japanese language qualified him, with additional training, to become a Navy translator and interrogator. He was posted to India from which he traveled through Burma and China. In pursuit of fluency in Japanese, he worked at the Japanese-American interment camp at Manzanar, California, where he helped to resolve prisoners' uprisings against inhumane living conditions.

When McLaughlin took up painting full time in 1946, Asian art and architecture loomed larger in his mind than the affinities he would later find in the work of Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Barnett Newman and Ellsworth Kelly.

"They made me wonder who I was," he wrote of classic Asian paintings. "Western painters, on the other hand"—implicitly those of the New York School—"tried to tell me who they were."

In McLaughlin's efforts to neutralise insinuating relations of figure and ground—touchingly evident here in a series of painted paper collage studies—he seems to have seen little linkage between his art and that of a Europe-oriented East Coast mandarin such as Robert Motherwell. With his biography in mind, we might think of him as the translator of Asian pictorial art' s vaporousness into Western Modernist painting's idiom of the tension between fullness and emptiness.

McLaughlin's paintings tend to be most persuasive where they are most severe. The flatness that Clement Greenberg saw as a mark of historical self-awareness in Post-war painting seems not to have mattered to McLaughlin. He concerned himself more with the kind of confrontation later associated with minimal sculpture—provoking viewers to take their own measures in various dimensions—than with his work's position in a lineage or an epochal project.

Yet we can find hints of occlusion, as of sliding screens, in some of McLaughlin's most insistently planar compositions, such as Untitled (April) (1953) and Untitled (1954). #1-1968 even contains a suggestion of shadowed alcoves that makes it difficult to keep Roy Lichtenstein out of mind.

Perhaps thinking to give McLaughlin a firmer foothold in the present, the show's principal curator, Stephanie Barron, commissioned the sculptor and furniture maker Roy McMakin to provide custom gallery seating in the form of twelve slat-back wooden chairs. I suspect that McLaughlin would have deplored this misstep, despite its intention to be inviting. He appears to have had little or no interest in what today would be called a work of art's "relational" potential.

On the day of my visit, a black chair faced the elegant black painting, #10 (1965). The chair's back slats rhymed too blatantly and altogether misleadingly with the white verticals in the painting. A conceptual artist might have retitled the ensemble "How to Destroy an Abstract Painting with a Chair."

The chairs may symbolise McLaughlin's stated wish that people spend time contemplating his paintings, an effort ideally in symmetry with the attention he invested in making them. But the fact that they are repositioned daily by staff to re-orient visitors (especially repeat visitors) toward specific paintings or specific walls reminded me of the last show in which I saw chairs given an active part: John Cage's off-site contribution to the 1991 Carnegie International Exhibition.

There Cage used chance operations daily to re-position works of art hung on the walls and chairs set around a single large room. On a given day a chair might have faced a work, an open window, another chair or a blank wall.

McLaughlin would probably have considered such an exercise anarchic, which would not have displeased Cage. But the McMakin chairs have a subversive, yet too stage-managed, effect on McLaughlin's show that likely would not have pleased either artist or composer.

• Kenneth Baker retired in 2015 after 30 years as resident art critic for The San Francisco Chronicle. He is an Art Newspaper correspondent based in San Francisco

• John McLaughlin Paintings: Total Abstraction, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, until 16 April