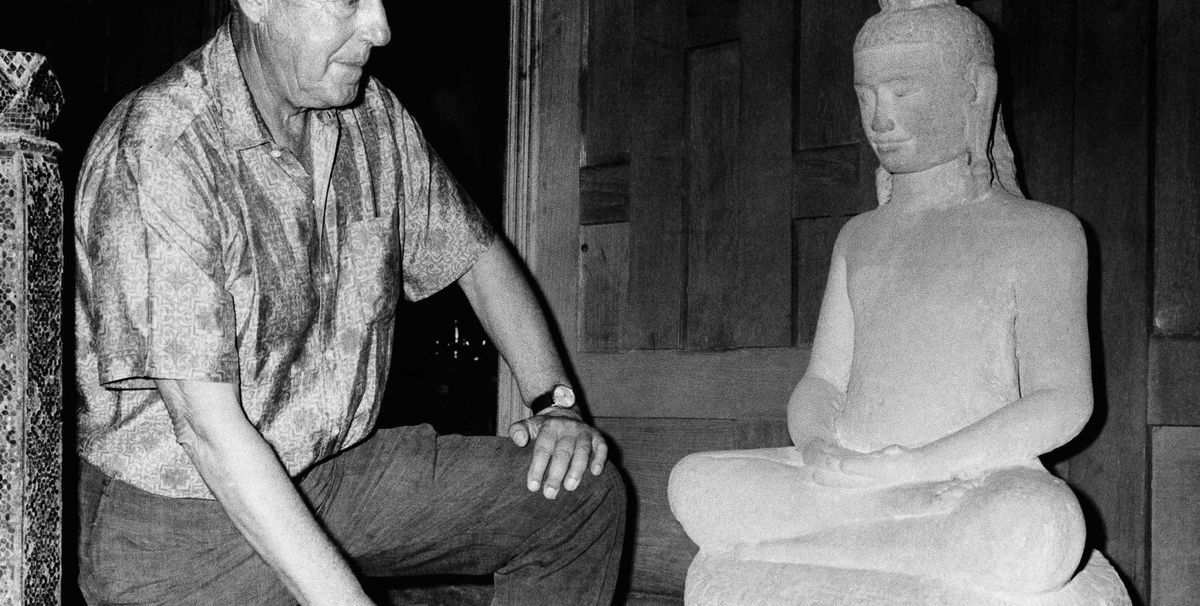

Buried in the 800-plus pages of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, a private collector’s estate is singled out for special relief from a hefty tax bill. It belonged to Jim Thompson, the American businessman and former intelligence officer who became known as Thailand’s “Silk King” for revitalising the industry there and opening it to the global market through moves like furnishing the original costumes for the Broadway hit The King and I (1956). Trained as an architect, he also built a major collection of textiles, Asian antiquities and decorative objects at his home in Bangkok.

Thompson mysteriously disappeared on 26 March 1967, while on holiday with friends in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands. Some thought he might have been attacked by wild animals or had a fatal fall while walking alone in the jungle; others believed he was kidnapped or murdered for political reasons. (Before his turn to the silk trade, Thompson was a former officer of the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the CIA.) Either way, after Thompson was declared legally dead in 1974, his nephew inherited all his property in Bangkok—as well as a large estate tax bill.

In 1976, the home and its collection were turned over to a charitable foundation, operating under the royal patronage of the Kingdom of Thailand. But the IRS still expected payment, and it took the Thompson family’s significant political influence (Jim was named after his grandfather, a Civil War general and diplomat) to settle the bill a decade later, with the Tax Reform Act officially allowing the transfer to be considered a charitable donation.

Today, the James H.W. Thompson Foundation supports the “conservation and dissemination of Thailand’s rich cultural heritage” through research, seminars, conferences, exhibitions and publications. It also operates the collector’s home in Bangkok as a popular museum, a library, artists residencies and a workspace for Conservators Without Borders, as well as the Jim Thompson Art Center, which organises exhibitions of contemporary art and design.