On the morning of 7 December, 1941—“a date which will live in infamy”, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it—a surprise Japanese military attack on Pearl Harbor, a US Naval base in Oahu, Hawaii, killed 2,403 Americans and jolted the United States into entering an international war on two fronts. To mark the anniversary this year, the Museum of World War II in Natick, Massachusetts, near Boston, has staged the exhibition The 75th Anniversary of Pearl Harbor: Why We Still Remember (until 7 January 2017).

The exhibition of around 100 objects (all drawn from the museum’s 500,000-work holdings) was made possible by the lucky acquisition three years ago of a Japanese collection of thousands of objects from the period. This includes “material no one ever sees about Japan celebrating” the attack on Pearl Harbor, says Kenneth Rendell, the founder and director of the museum. The show also features significant American documents, such as the telegramme declaring the attack, which reads: “AIRRAID ON PEARL HARBOR X THIS IS NO DRILL”. But the story starts years before, with Japan’s invasion of China in 1937, including magazines showing Japanese soldiers standing on the Great Wall of China and propaganda to encourage Japanese settlement in the agriculturally rich country.

The exhibition also explores American wartime propaganda related to Pearl Harbor, with the prominent slogan “Remember Pearl Harbor”. “It became the battle cry at the beginning of the Second World War,” Rendell says, and was put on all sorts of objects presented in the exhibition, from license plates to bizarre memorabilia. The “most whimsical”, Rendell says, are pairs of miniature panties that read, “Don’t get caught with your pants down, Remember Pearl Harbor,” which were going to be pulled from the show but stirred too much media interest.

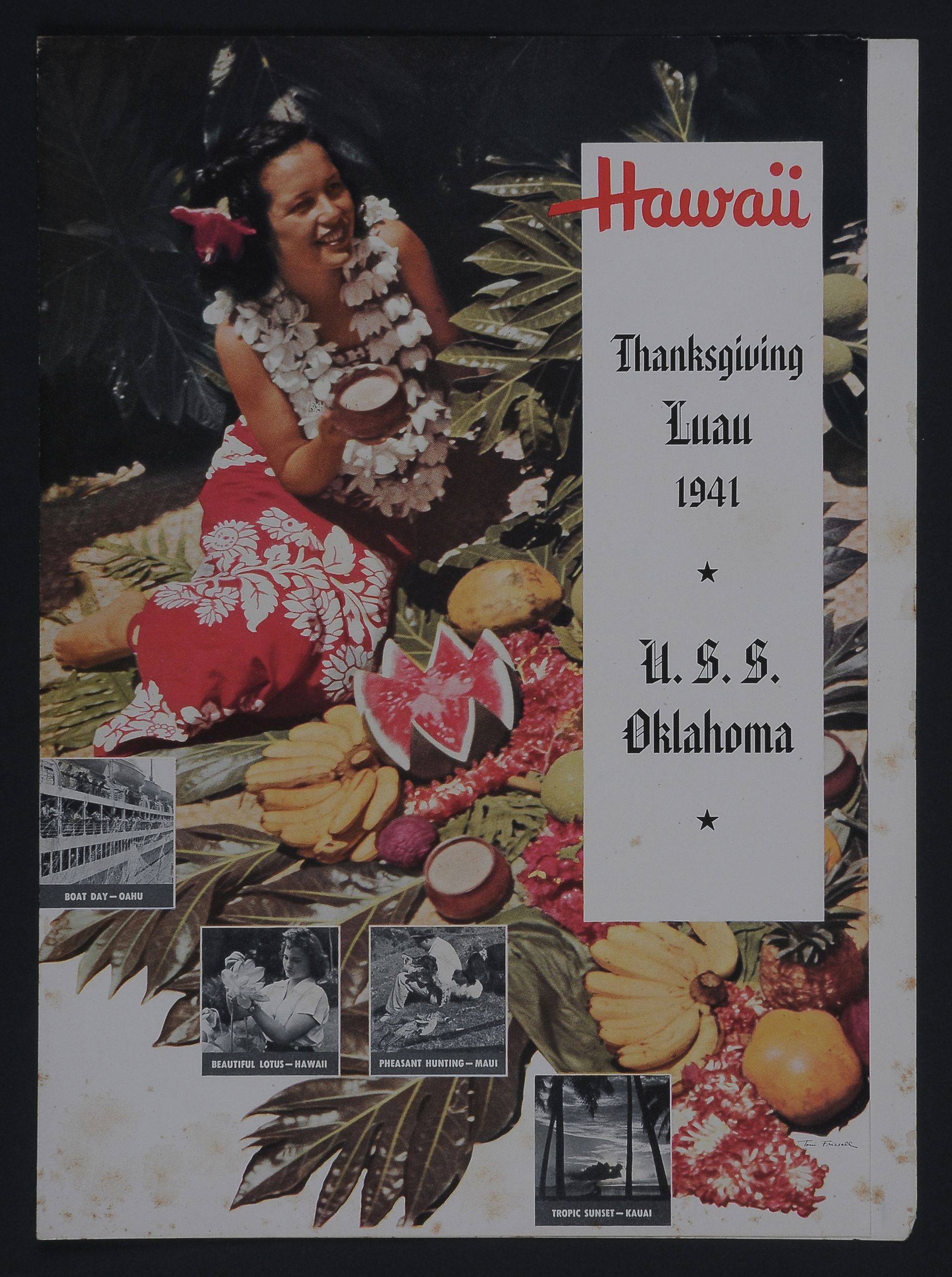

One way the show conveys the sense of shock that hit the country is by illustrating the jolly atmosphere in Pearl Harbor and nearby Honolulu shortly before the attack. A colourful announcement for the 1941 Thanksgiving luau on the battleship USS Oklahoma, featuring a hula girl and a lush spread of tropical fruit, is juxtaposed with a photograph of the torpedoed vessel, on which 429 crew members died. This encapsulates “that contrast of going from paradise to hell overnight”, Rendell says.

It also aims to give multiple perspectives on the event. A particularly poignant display of the human side of the war, and a witness to the extreme injustices inflicted upon Japanese Americans during wartime hysteria, is a series of objects from a Japanese-American couple: Tom Kasai, who served in Europe, and his wife, Ruth, who was imprisoned during the war at the Poston internment camp in Arizona, including a telegramme sent to Ruth at the camp to tell her Tom was wounded in France. The show also includes a poster from April 1942 ordering “all persons of Japanese ancestry” in an area of Los Angeles to be “evacuated”—ie, taken into detention centres.

“People use their own minds [visiting the show]—we don’t tell them what to think, we present material artefacts, photographs, documents that will let people experience it as close to being there,” Rendell says. The museum, the world’s largest dedicated to the Second World War, “is not a memorial—it is much more an experience that war is personal and complex and horrible,” he adds.

“Nothing good comes out of Pearl Harbor,” Rendell says. “There’s no way to see it as any glory. But I don’t think you can ever see war as having glory. There are individuals that did heroic things… But there’s no glory in killing people or getting killed.”