In the winter of 1942, the artist and designer Isamu Noguchi was living in the Hollywood guesthouse of the film star Ginger Rogers while working on a marble bust of her that is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. But he put down his chisel for a while after US President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, which led to the internment of around 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

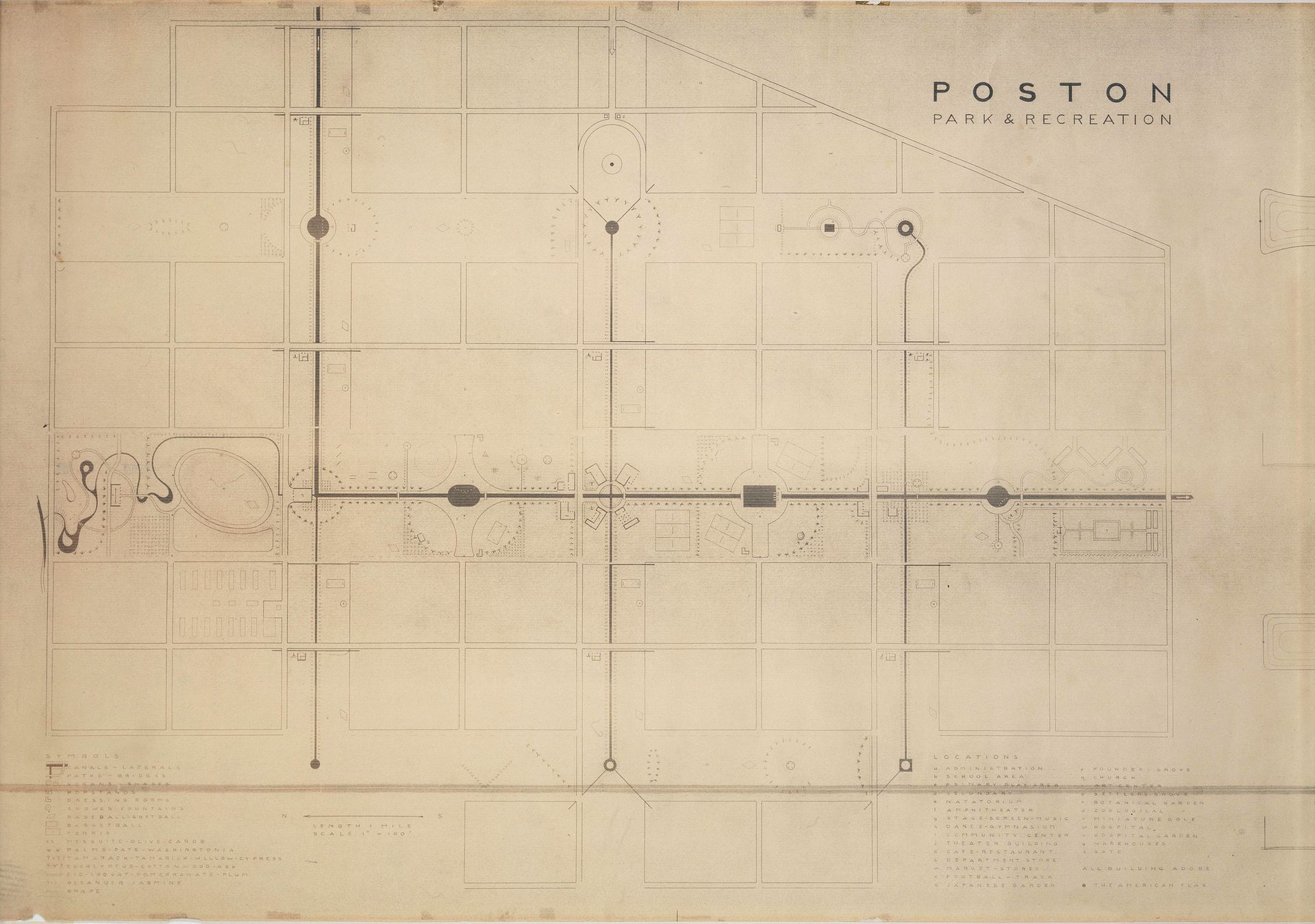

As a resident of New York, Noguchi, who was born to a white American mother and a Japanese father and grew up between the two countries, was not forced to “relocate”. But the artist chose to voluntarily enter the Poston detention camp in Arizona in the hopes of helping to improve the conditions there, for instance by building facilities like swimming pools. “He tried to use his moral authority as a well-known Japanese American at this moment,” says Dakin Hart, the senior curator at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York. As the artist said at the time: “Thus I willfully became part of humanity uprooted.” Noguchi ended up receiving no support from the government to realise his plans, and was unable to leave the camp for seven months.

This period of his life is the subject of an upcoming year-long show at the Noguchi Museum, Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center that opens 18 January 2017. Organised by Hart, the exhibition does not attempt to give visitors an in-depth historical perspective on the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War, but to focus on how that historic moment affected the artist personally and in his work. “It’s really, really important to note that Noguchi’s experience is not representative of the Japanese American experience around internment, because he had choices,” Hart says. “We’re really looking at Noguchi, his experience, his words… [the show is] a complement to the larger story.”

The museum is presenting archival material and around 25 works from its collection, presented chronologically, starting with a 1941 bust of the theatre actress Lily Zeitz and ending with two installations of Noguchi’s sculptures from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s, Deserts and Gateways, which show how Noguchi’s time at Poston continued to influence his work throughout his life. “He became an expert in making pieces that are like Dorothy’s ruby red slippers that can take you somewhere else—that are capable of psychological transport,” Hart says of the works in the Gateways series, which include “portal”-like forms, such as voids and doorways.

The titles of some of his wartime works, like The World is a Foxhole (1942-43) and This Tortured Earth (1942-43), put his mindset in sharp relief, while other works, like a driftwood sculpture from 1943, are untitled. The poignant figurative onyx piece Mother and Child (1944-45), meanwhile, “represents a return to something simple, basic, solid, life-affirming”, Hart says.

Self-Interned seems especially timely given the discourse surrounding the election of Donald Trump, including a recent television interview between the Fox reporter Megyn Kelly and a Trump supporter, Carl Higbie, who called Executive Order 9066 a “precedent” for a proposed national registry of Muslims in the US. For the moment, Hart says, the museum staff have not been able to meet and talk about possible programming that relates Noguchi’s internment to current events. Hart adds, however, as a well-known multi-cultural, biracial and “culturally synthesising” individual: “had Noguchi been alive today, he’s someone everyone would have wanted to hear from on this subject”.

• Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center, Noguchi Museum, Queens, New York, 18 January 2017-7 January 2018