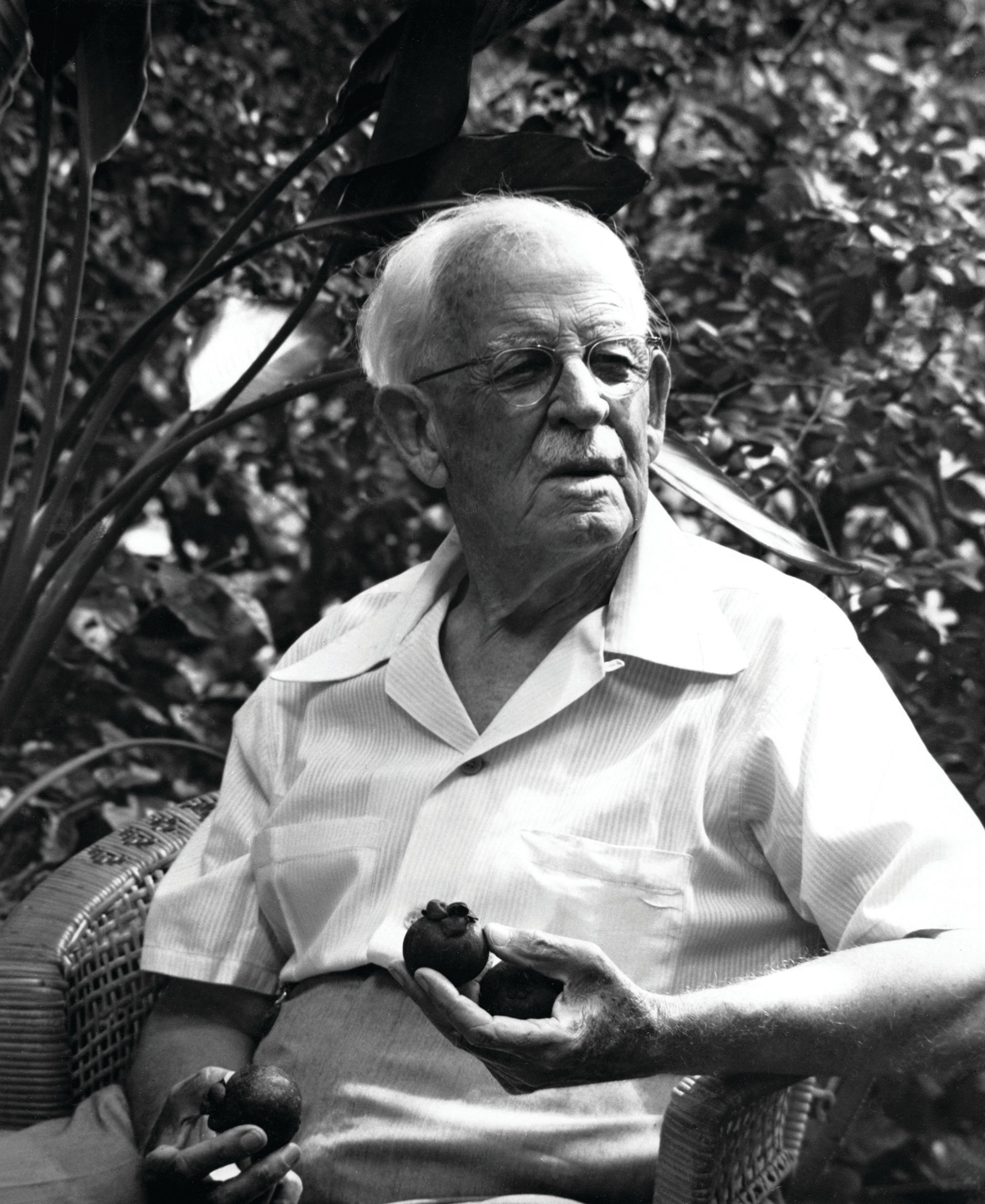

In the middle of Coconut Grove, Miami’s historic neighbourhood on the edge of Biscayne Bay, is the Kampong. The eight-acre tropical garden and historic home was built by David Fairchild, a botanist and “plant explorer” who ran the US Department of Agriculture’s Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, founded in 1898. His office scoured the globe for fruits, vegetables and grains that could expand the US farming and food industry. Fairchild brought many of these specimens to what was originally his family home, which has since been preserved as one of five National Tropical Botanical Gardens (the other four are in Hawaii). For its first permanent art installation, the Kampong has commissioned the artist Mark Dion to recreate Fairchild’s office and laboratory. The project, supported by a grant from the Knight Foundation and Miami-Dade county agencies, opens to Art Basel VIPs on 1 December, and to the public from 2 to 4 December.

• Mark Dion will be in conversation with Tim Rodgers, the director of the Wolfsonian-FIU, at Art Basel in Miami Beach on 2 December, 5-6pm

The Art Newspaper: Tell us about David Fairchild.

Mark Dion: He’s a really interesting guy. His passion was tropical fruit; he loved the tropics and things like mangoes, avocados and passion fruit. The American palate was very narrow, so his introduction of things like that was tremendous. At the same time, his department was interested in solving some real problems, like finding plants—sorghum and wheat—that would grow in areas like the Dakotas and Montana, since nothing from Europe was growing there. They sent people to the Russian steppes and brought back these hearty winter wheats. That made the northern part of the grain belt valuable. He was [also] responsible for bringing over Japanese cherry trees to Washington, DC.

The people I tend to create work about were popularisers of biology and natural science. They weren’t like so many contemporary scientists who are satisfied to keep their discoveries within the scientific community; they actually wrote for the public. Fairchild was very involved in the establishment of the National Geographic Magazine and Society, and he wrote books that were meant for broader audiences.

You’re interested in people who help others understand how science applies to their own lives.

Absolutely. Fairchild understood the potential for Florida to become an agricultural juggernaut. He brought dates back from the Middle East and established the date palm industry in California. That’s a big deal. But because Fairchild’s interest was tropical, it was always a bit marginal for the Department of Agriculture, and he had a hard time. There was a concern over introducing pests, diseases like chestnut blight, and invasive plants like kudzu. The first shipment of cherry trees to Washington were actually burnt because they were believed to harbour pathogens. All of that began to outweigh the benefits [for] the Department of Agriculture and so they eventually killed the programme.

Why do this project at the Kampong?

It’s just this magical, fantastical place in the middle of Coconut Grove. South Florida is so interesting to me because it’s really the best and the worst in the nation, side by side. The cultural diversity and nature is wonderful. But it’s also fraught with development. It really is where we paved paradise and put up parking lots. When you walk through the gates of the Kampong, you are walking into a different era. You’re seeing Coconut Grove from the early part of the 20th century.

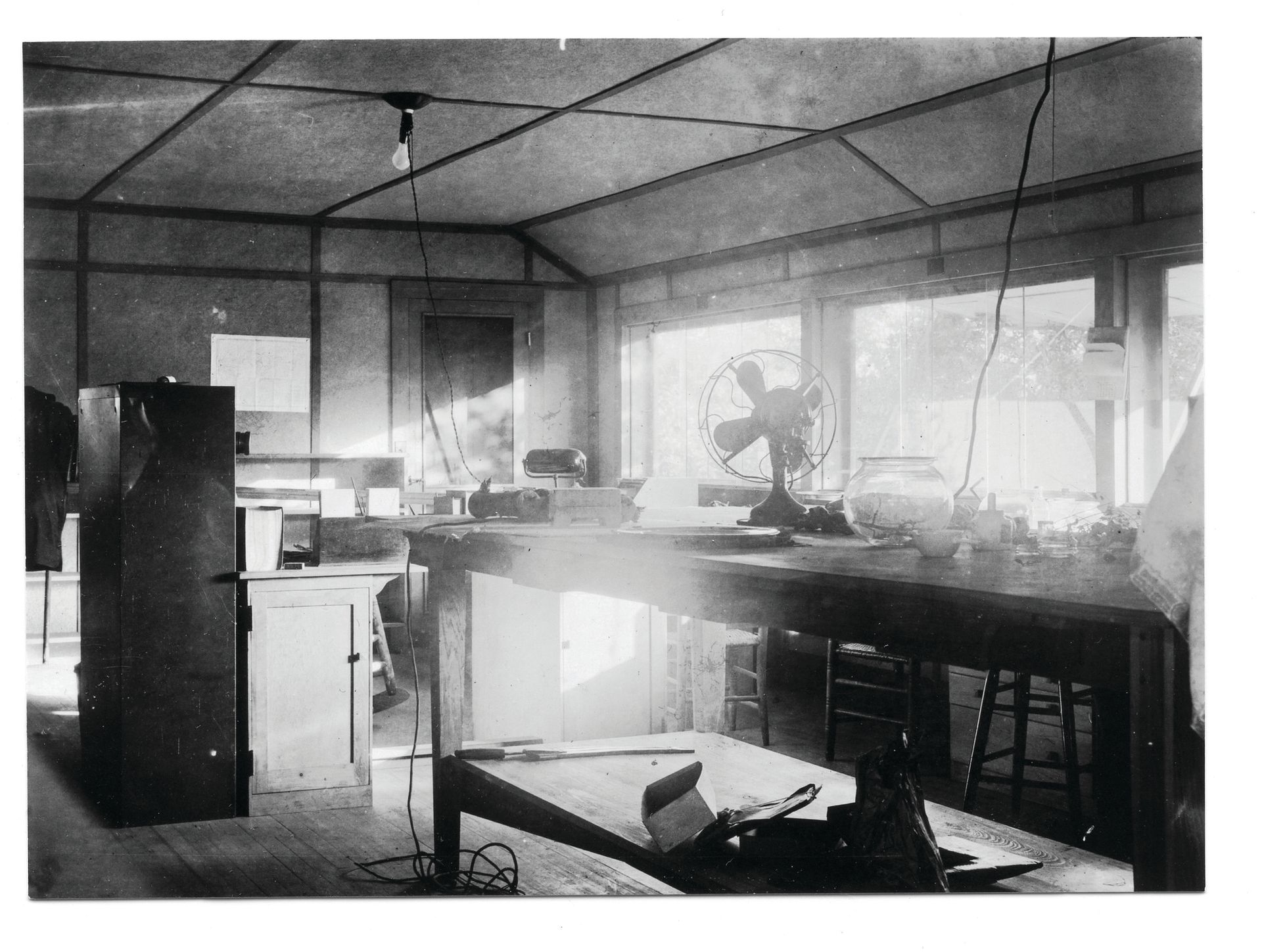

When I saw the building with Fairchild’s laboratory, it was just a shell. His table, desk and typewriter were still there, but that’s about it. You felt that Elvis has definitely left the building. Instead, it should feel like Fairchild has just stepped out for lunch and that he could walk back in at any moment. So that’s what I’m striving to do. We have some photographs, showing what the study and laboratory were like, so we know his aesthetic. But I’m using those more as a creative guideline to be a little more exuberant.

What kinds of materials have you used to bring him to life?

There’s a lot of period scientific apparatus. I bought a 1915 microscope, since there’s a microscope in every photograph of his laboratory, so you know that was a central, useful tool. I’m highlighting his typewriter, ink bottles and pen nibs, since this was before the ballpoint pen existed. This was where he wrote his popular works for National Geographic and conspired with his friend, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who spearheaded the campaign to make the Everglades a National Park.

I’ve also read he was a photographer and illustrated many of his books.

Yes, he was a big photographer. He married Marian Bell, who was Alexander Graham Bell [the inventor of the telephone]’s daughter. That gave him a lot of access to technology at the time. One of the most beautiful things that he and Marian did together was create the Book of Monsters [featuring close-up photographs of insects]. It’s one of the first books on macro photography in America. Theirs was an era of invention and playfulness, so I wanted [the project] to have that kind of joyfulness and weirdness.

Key works

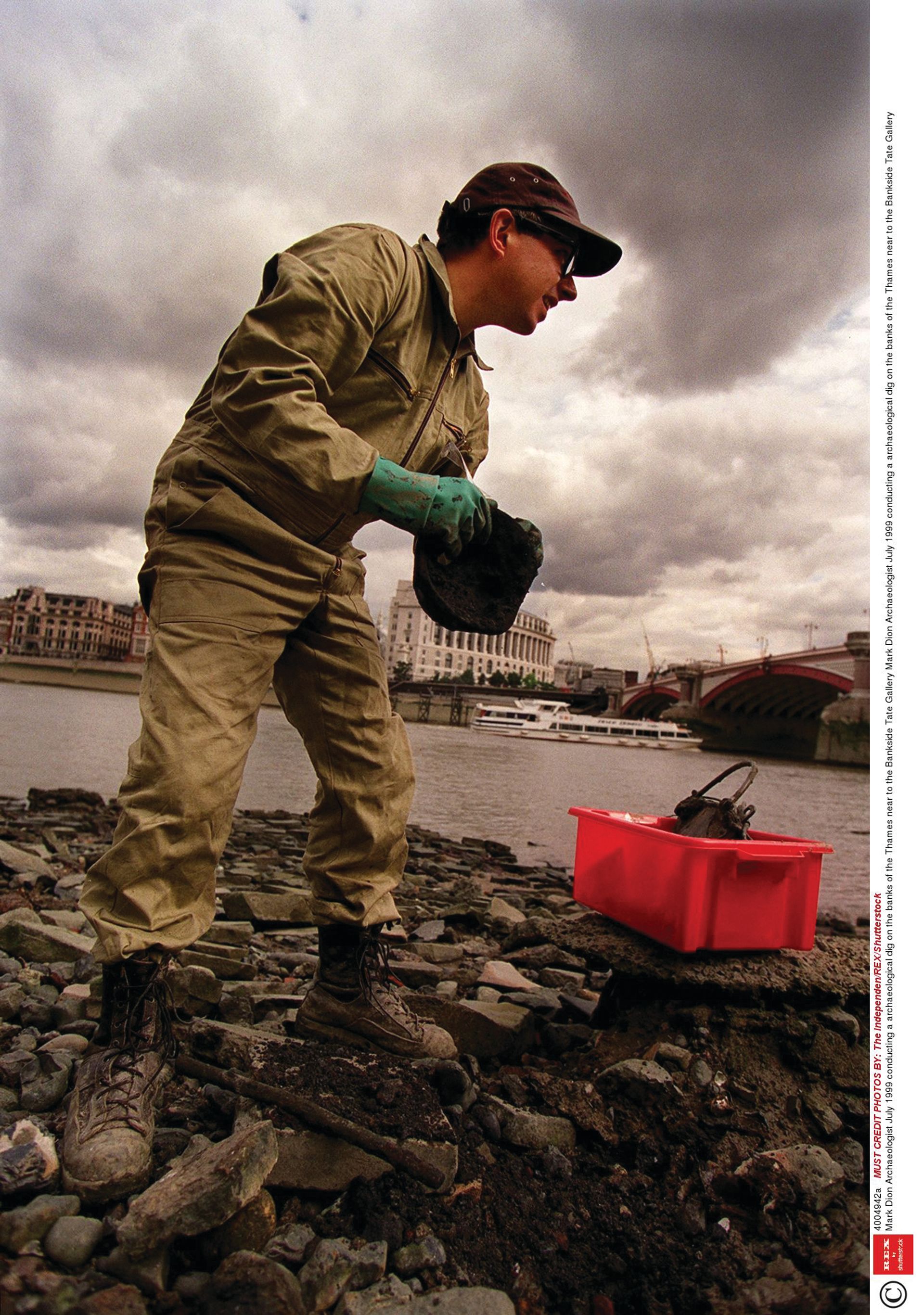

Tate Thames Dig (1999)

The summer before Tate Modern opened in the former Bankside Power Station, Dion and a team of volunteer urban archaeologists combed the banks of the Thames at low tide, looking for objects discarded by Londoners. Their finds included artefacts like clay pipes, shards of delftware and oyster shells, as well as contemporary detritus like plastic toys and credit cards. The objects were cleaned and presented in large cabinets—a slice of the city’s history and society through the centuries.

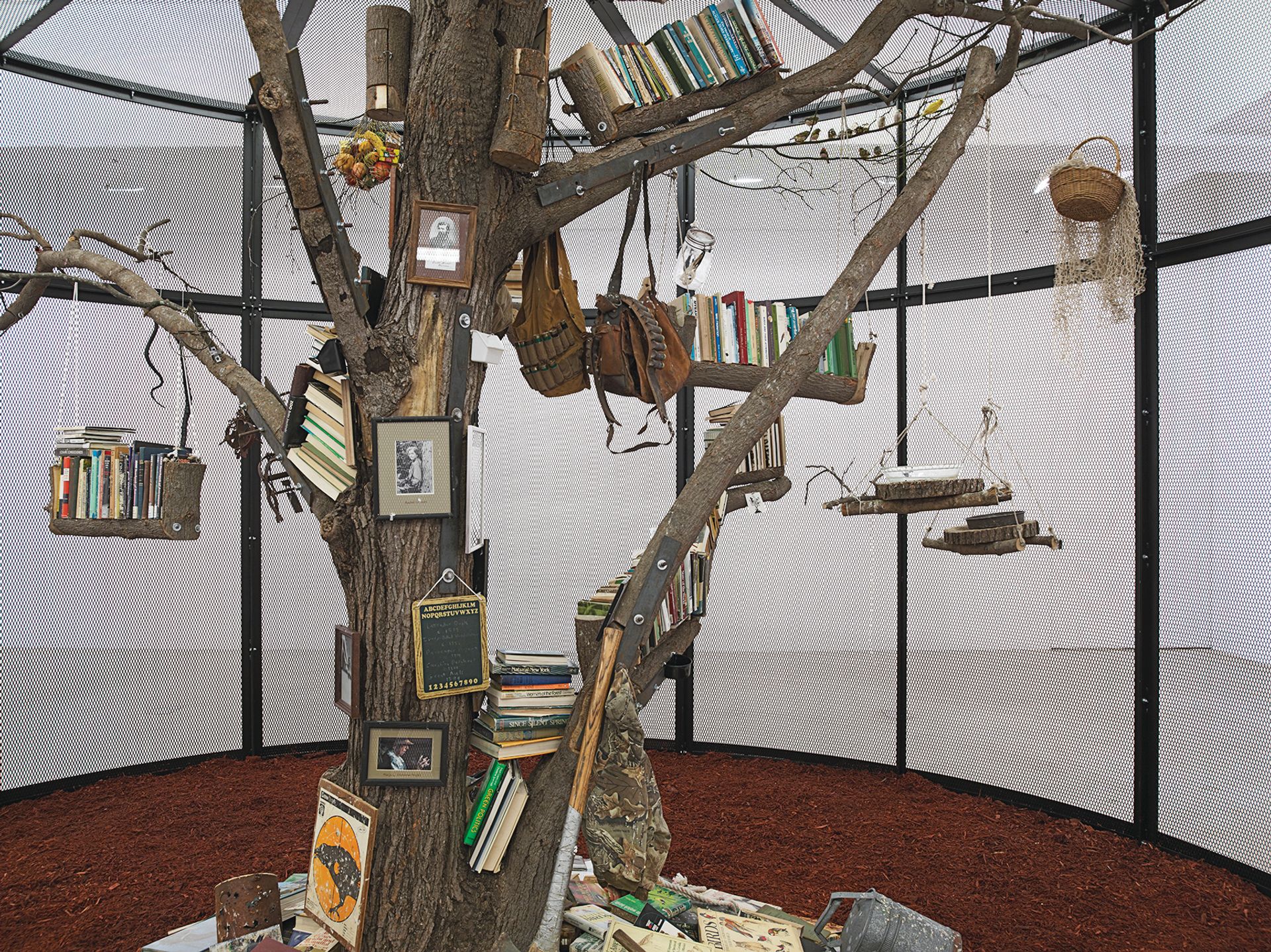

The Library for the Birds (1993-2016)

Since the 1990s, Dion has created a series of reading rooms built around trees, stocked with books about human interaction with the avian world and populated by a small flock of live finches. “The idea is based on this absurdist conceit of a library for birds,” Dion told T Magazine. “But of course, there are birds defecating on the books, and their indifference to this human knowledge is rather striking.”

The Undisciplined Collector (2015)

This installation presents the den of an imaginary collector in 1961—the same year the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, where the work is housed, was founded. It contains objects drawn from across the school, including works from the Rose, books from the library, artefacts from the classics and anthropology departments, and even trophies from Brandeis Athletics.