Art-historical references abound at Art Basel in Miami Beach—if you know where to look. When we took a tour of the fair with Harry Cooper, the head of the department of Modern art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, history seemed to be his guide as he selected some of his favourite works on show. Cooper had the chance to present a more comprehensive narrative of 20th- and 21st-century art with the opening of the National Gallery’s expanded East Building this autumn. “You have to see art in development over time, with movements responding to one another,” Cooper told us in September. And in each work we discussed at the fair, he noticed allusions to earlier traditions.

Dana Schutz

Expulsion (2016)

Petzel

“The first thing I noticed is that you can smell the paint; it’s still that fresh,” Cooper says, pointing to still-wet sections of a work by Dana Schutz. “But the historical reference also caught my eye. It reminds me of the Masaccio expulsion,” he says, referring to the Florentine master’s fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, which was painted around 1425. In the figure on the left, he sees what “looks like an escapee from Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, with all that warm fleshiness and those sharp angles. But maybe the best part is the insects at the bottom. They look like they come out of a late work by Philip Guston.”

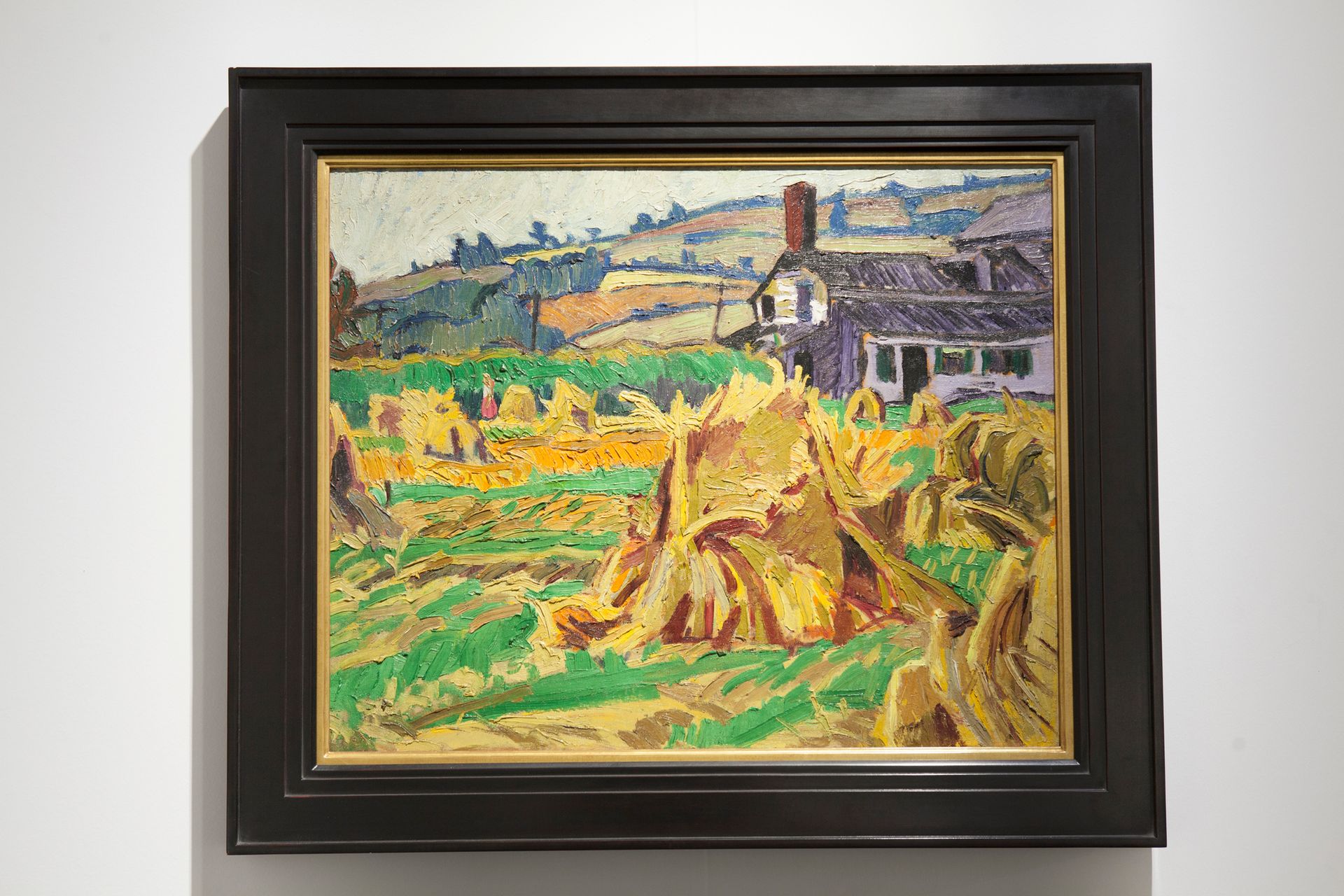

Stuart Davis

Corn Shocks, Tioga, Pennsylvania (1919)

Menconi + Schoelkopf

Early in his career, Stuart Davis was enthralled by Vincent van Gogh, “but it wasn’t just a phase”, Cooper says. The US painter’s early interest in the Dutch post-Impressionist never deserted him, partly because Davis was a landscape and still-life painter. “But he worked even more quickly—there’s a lot of wet-on-wet technique in this painting—whereas Van Gogh made most of his paintings more deliberately.” Although this work speaks to Davis’s burgeoning self-confidence, it left significant room for growth. “This one is still a little immature,” Cooper says. “The yellow/purple complementarity is straight out of a textbook, and that warm brown chimney is more naturalist, an anomaly, as if out of a painting by Robert Henri [one of Davis’s teachers].”

Joan Semmel

Untitled (2016)

Alexander Gray

“To see someone drawing beautifully from the figure is a rare thing in contemporary art,” Cooper says. “There’s a level of abstraction that enters into this because of the cropping. The body leaks out onto the page, and the negative spaces inside are the ones that are defined. It reminds me of Matisse. He used to get so close to his models that he was practically on top of them. In Semmel’s case, she was often her own model, taking photographs of herself, but this drawing has none of that flat feeling of copying a photograph. She has internalised the sense of the body.”

Martin Puryear

Niche (1999)

Matthew Marks

“Puryear is such a serious, thoughtful artist, and this unusually large-scale drawing is powerful,” Cooper says. “It almost feels like something you can walk into, with this three-dimensional niche in a wall, and yet it’s hard to tell if it’s convex or concave. Only the lines that run across give you a sense of perspective. So, with that ambiguity, it is much more than just a sculptural study.” The artist often defamiliarises vaguely recognisable objects and “this one almost seems like a head, with that bulbous shape”, Cooper says.

Franz West

Untitled (2010)

David Zwirner

Irreverence and playfulness are the qualities we most associate with Franz West. Yet this sculpture—which Cooper grants has something “radically informal or unfinished about it”—leans towards figuration. “It feels like a head or a helmet, like there’s some skeletal structure underneath, or some anatomical form. In that way, it’s very traditional, implying an interior through the surface alone.” Cooper also sees something darker in this papier-mâché, gauze and steel sculpture. “There’s a sense of German Romantic suffering” to it, the curator says.