The first Whitney Biennial opened in New York on 22 November 1932 in a climate of healthy liberal optimism. Two weeks earlier, the Democratic nominee for president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had defeated the incumbent Republican Herbert Hoover in a landslide. In a radio message just after his victory, Roosevelt heralded a “national victory for liberal thought” and promised an “orderly recovery” to a nation still deeply mired in the Great Depression.

The director of the Whitney Museum of American Art at the time, Juliana Force, echoed his enthusiasm on the occasion of the institution’s inaugural survey of American art. “An increasingly liberal spirit has broadened the scope of these exhibitions,” she told the New York Times, “so that in recent years they have assumed greater importance to both artist and public.”

Model under stress Such idealism is difficult to imagine today, as right-wing politicians gain influence around the world. The election of Donald Trump, the unfolding of Brexit and forthcoming presidential elections in Austria (4 December) and France (23 April 2017) put stress on liberalism and, by extension, on the modern biennial model, which values a broad and diverse presentation of ideas. In an increasingly illiberal world, what use is a biennial?

According to Fred Bidwell, the chief executive of the forthcoming Front International in Cleveland, there has never been a better time to organise such shows. Front is one of four new biennials due to launch in the US over the next few years. The trend is the subject of a talk today at Art Basel Miami Beach. “Two days after the US election, I met Jens Hoffmann, one of our artistic directors,” Bidwell says. “And the first thing out of his mouth was, ‘we need to do this now more than ever.’”

But biennials are not inherently tied to liberalism. The first such show, which opened in Venice in 1895, was organised to commemorate the wedding anniversary of King Umberto I and Queen Margherita of Savoy. The king, far from being progressive, was a right-wing nationalist and imperialist. Three years after the show, he decorated one of his generals for massacring 80 striking workers in Milan who were protesting the escalating cost of bread.

In 1930, Benito Mussolini transferred directorship of the biennale from local authorities to his central government. For the next several editions, the show became an explicit celebration of Fascist populist values and was integrated into what Mussolini called a “move toward the people”. Film, music and decorative arts were given pride of place as a way to appeal to the common man rather than the elite.

Only after the end of the Second World War, with Fascism in defeat and liberalism in assent, did biennials change tack. In Germany in 1955, Arnold Bode founded Documenta as an explicit critique of German political history. The inaugural show focused on the many forms of Modernism that Hitler had labelled degenerate. Around 570 Fauvist, Cubist and Expressionist paintings and sculptures by nearly 150 artists were installed with little regard to a work’s national origin, thereby underscoring the universal sweep of Modernism.

This global liberalism, however, is not the model for most American biennials. “There never was a particularly internationalist perspective in the US in terms of large-scale exhibitions,” says Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, who organised Documenta in 2012 and the Istanbul Biennial in 2015. This is partly a product of the country’s size. In the US, cultures and traditions are dispersed across 3.8 million square miles of land. It makes sense to start at home.

Pride of place This remains the case for the country’s newest biennials, which often grow from and focus on local communities. The idea behind the Honolulu Biennial, which has its first edition next year, is to focus on how the Hawaiian landscape generates regional culture. “We’re looking at this place and trying to understand how it shapes who we are,” says the show’s curator, Ngahiraka Mason. “Creative practice comes out of the influence of geography. That’s the thing that shapes you.”

But culture also shapes its surroundings. In the 1960s, American artists took to working on a massive environmental scale. Projects like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) brought art to desolate places—an approach that Neville Wakefield, the artistic director of Desert X in Palm Springs, hopes to reawaken with a series of commissions. “The works should be in some way generated out of the conditions of the place, as opposed to some of the cut-and-paste versions we know of public sculpture,” he says.

What can a biennial really do? How artists work is one thing, but the real political question for any biennial is its organisational model. Prospect New Orleans, which opens its fourth edition next year, takes place across various existing sites in the city. This kind of multi-institutional show is more complex than even the most ambitious single-venue exhibition, and the approach says much about its aims.

“Everything we do relies on deep and trusting relationships,” says Brooke Davis Anderson, the show’s executive director. “We delve deeply into every neighbourhood and by default rely on our partnerships.” The last edition, which opened in 2014, took place in 18 venues and included 58 artists. There is a pluralist liberal model at work here: although the exhibition had a single artistic director—Franklin Sirmans, now the director of the Pérez Art Museum, Miami—it was, like all biennials, too large to fit a single vision.

This model also carries risks. Sprawling biennials often struggle to find clear curatorial footing. Any show that includes both the Minimalist sculptor Larry Bell and the political group Occupy Museums (as the forthcoming 2017 Whitney Biennial does) will find it practically impossible to maintain a clear position. With liberalism now under assault, big, bold, clear ideas are more necessary than ever. This is not a curatorial responsibility per se, but it is a responsibility of citizenship in an increasingly illiberal world.

• Talk on new biennials in the US, Art Basel in Miami Beach, Miami Beach Convention Center, 1 December, 6pm

Where it all began: two landmark US biennials

The first periodic contemporary art show in the US opened in Pittsburgh in 1895. The Annual Exhibition, as it was then known, was founded by the industrialist Andrew Carnegie as a way to make the Steel City into an art centre. His intention was to exhibit what he called “the Old Masters of tomorrow”, and early iterations of the show included works by then-radical artists like Henri Matisse, who won the exhibition’s top prize in 1927. Now known as the Carnegie International, the show opens its 57th edition in 2018 under the artistic directorship of Ingrid Schaffner.

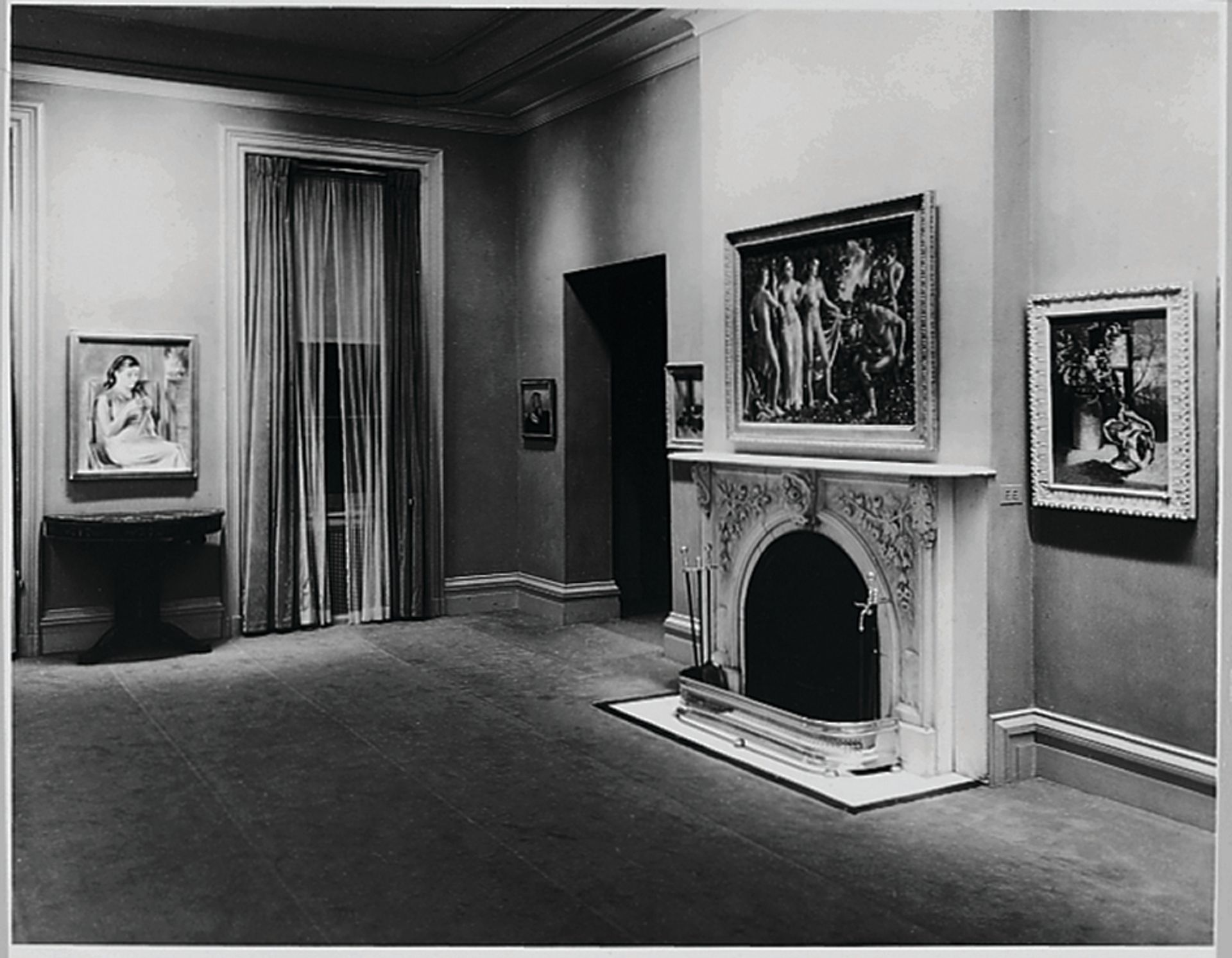

The Whitney Museum’s annual show, which launched in 1932, focused more specifically on American artists. Significantly, organisers jettisoned the jury system and instead invited a group of artists to self-select what paintings (the only medium included in the inaugural show) they wanted to include. “Each artist is his own jury,” the New York Times reported at the time. The focus on American artists, like the focus on paintings, has since relaxed: Kuwait, Iran and Vietnam are among the countries of origin of artists included in the next edition, which opens in May 2017.

New US biennials and triennials Front International, Cleveland,

July-September 2018

Desert X, Palm Springs,

25 February-20 April 2017

Honolulu Biennial: Middle of Now | Here,

8 March-8 May 2017

Detroit Biennial

Dates TBD