The decision by the Nashville-based couple Spencer and Marlene Hays to donate 600 turn-of-the-century works to the Musée d’Orsay in late October has prompted French and US art professionals to question why the prestigious collection went to a French rather than a US institution.

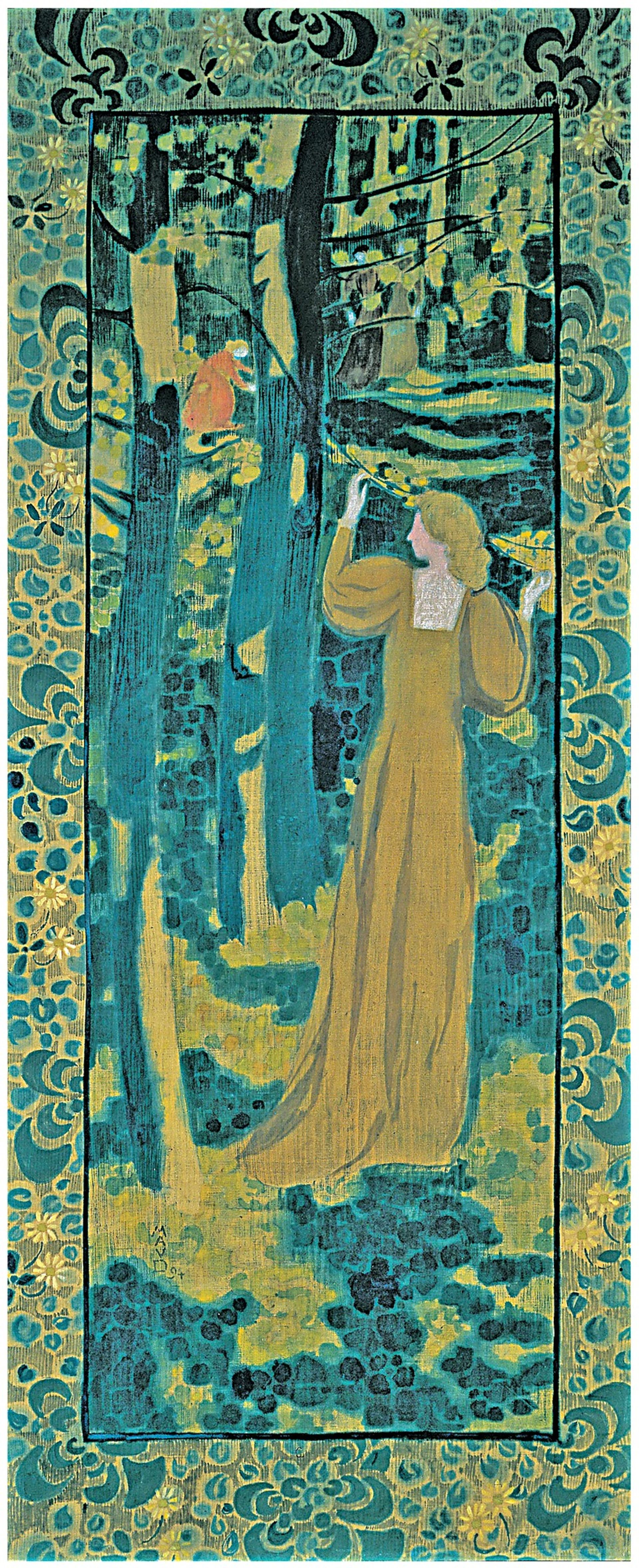

The Hays donation is the largest gift a French museum has received from a foreign donor since 1945. The couple’s holdings include important pieces by Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis and Odilon Redon. The gift will allow the Orsay to grow its collection beyond Impressionism and better represent the Nabis painters, a wing of the post-Impressionist avant-garde. The couple, who first visited France in 1971, plan to send the collection to Paris in stages, beginning with 187 works.

Guilt trip The Hays say they want to return the works to the country where they were painted and were won over by the Orsay’s willingness to adhere to their wishes. “We wanted it in one place, we want it all together, we don’t ever want any of it to be sold and we never want it to be stored; we always want it on the wall,” Spencer Hays told the New York Times. Marlene Hays told the paper she “felt guilty” at first for sending the works abroad, but realised many Americans would see them in the Orsay, which welcomes hundreds of thousands of US tourists each year.

Some suspect the Hays were swayed by French museum protocol, which prohibits deaccessioning. “Works in public collections in France are inalienable, unlike US museums, which can sell works to buy others,” the French art critic Bénédicte Bonnet Saint-Georges wrote on the website La Tribune de l’Art. US museums are also increasingly focused on acquiring contemporary works, while major encyclopaedic museums already have significant late 19th-century holdings, notes the New York-based arts consultant Geri Thomas.

The Musée d’Orsay agreed to show the works, which are technically owned by the French state but will remain accessible to the couple until their deaths, in a single space rather than dispersed throughout the museum. A spokeswoman confirms that the museum will be reconfigured to accommodate the gift. The library and archives on the fourth floor will be transformed into a dedicated 900 sq. m space for the Hays’ collection.

The library and archives will be transferred to a nearby building, which will also house a research centre dedicated to the Nabis movement. The museum’s director Guy Cogeval, who was integral in securing the Hays gift, will direct the centre after he steps down from his post next year.

Some are not surprised that the Orsay agreed to the collectors’ terms. “Donors these days can dictate terms and do. If museums worldwide want a collection, they will swallow hard and accept conditions,” says one New York-based art professional.

Long-distance donations The move has also ignited debate about why and how collectors donate to museums abroad, and who benefits from such “cross-border” gifts. The New York-based couple Thea Westreich and Ethan Wagner also chose to donate some of their collection to France. In 2015, they sealed a deal to divide their US and international contemporary works between the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris (550 works to the Whitney and around 300 to the Pompidou).

Westreich says that “cross-border” donations are unusual, but that the talks progressed with the counsel of Adam Weinberg, the Whitney’s director. “It was clear that the Centre Pompidou highly valued the European artists we had collected [including Philippe Parreno, Eija-Liisa Ahtila and Keith Tyson]. In fact, the vast majority were on the Pompidou’s wish list. That circumstance, on top of the Pompidou’s distinguished history, made the choice clear,” she says.

Asked about terms attached to the gift, Westreich adds: “Given the Centre Pompidou’s stated desire to put on a large exhibition of works from our gift and to co-publish the collection catalogue in French, our only stipulation was that the museum always follow the artists’ wishes regarding the installation and conservation of their works.”

The decision to donate to institutions beyond one’s homeland sometimes comes down to personal preference. Maya Rasamny, the London-based co-chair of the Tate’s Middle East and North Africa Acquisitions Committee, says that she is considering giving works by Middle Eastern artists from her collection to universities in the US because two of her children are studying there.

The most poetic response comes from the Swiss collector Uli Sigg, who donated 1,463 contemporary Chinese works to the M+ museum in Hong Kong in 2012. “It reflects my intention to return something to China for what it has allowed me to experience over the last 33 years: an incredible journey, whose most intense core has been formed by so many encounters with Chinese artists,” Sigg says.