The narrative around the November auction season differs depending on who you talk to. Some dealers, such as David Nahmad, lamented the lack of top-quality works coming to market this season. “Remember last year? They had a nude by Modigliani, they had [Pablo Picasso’s] Women of Algiers”, he said. True, there were fewer $20m-plus lots, and the total value of consignments has fallen steadily over the past two years. However, sell-through rates at the evening sales ranged from 81% to 94%, suggesting sustained demand, even in a less bullish market. The much-touted, astronomical totals achieved in 2014-15, when Christie’s and Sotheby’s fetched billions, should be seen as an anomaly rather than a benchmark.

“The volume of trophy works might be lower compared with the bumper years of 2014 and 2015, but clearly there is still a measured appetite,” says Jussi Pylkkänen, the global president of Christie’s.

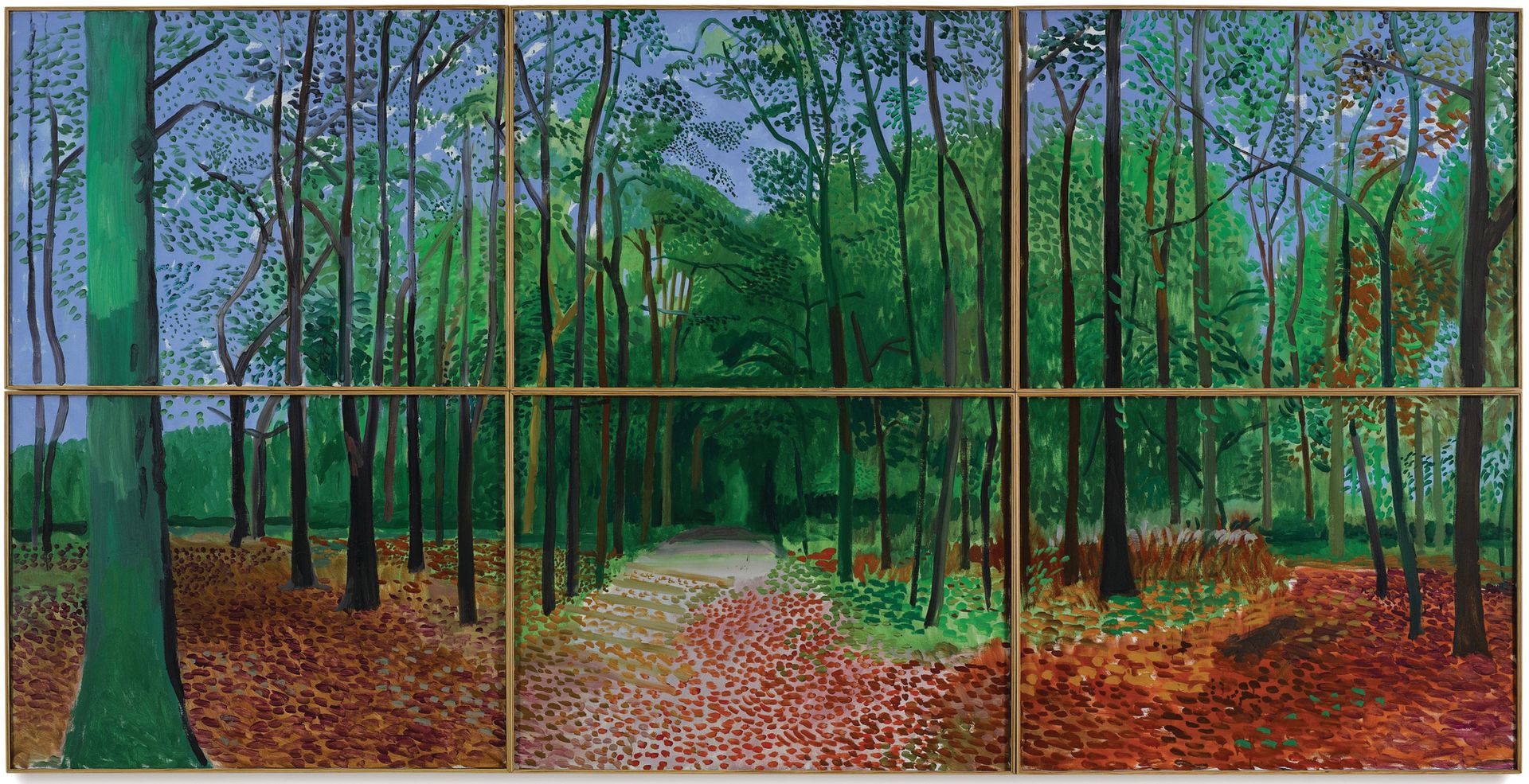

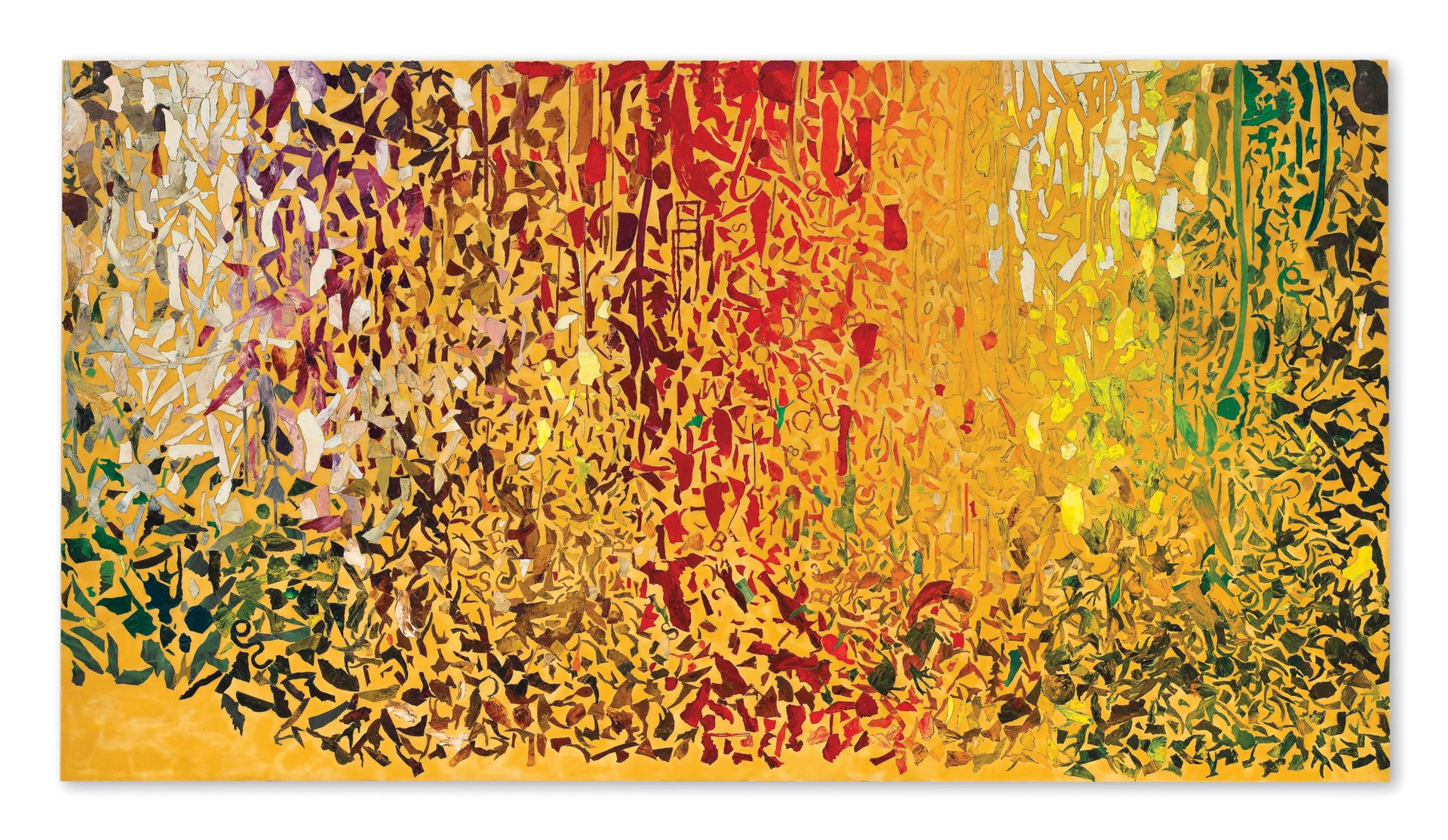

Several artist records were set: at Sotheby’s for David Hockney, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and László Moholy-Nagy; at Phillips for Carmen Herrera and Mira Schendel; and at Christie’s for Willem de Kooning, Claude Monet, Wassily Kandinsky, Jonathan Horowitz, John Currin and Giuseppe Gallo.

Nevertheless, there was noticeably thin bidding on many works and the atmosphere was subdued at points, with the auctioneers struggling to coax bids out of hesitant buyers.

Including the buyers’ fees, totals for all five auctions fell within their estimates except for Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sale, which exceeded its estimate largely thanks to Monet’s record-breaking Meule (1891). One of the artist’s last haystacks in private hands, it fetched $81.4m with fees, close to twice its unpublished estimate of around $45m. The fact that it did not carry a guarantee signals an encouraging degree of confidence on behalf of its seller—and the auction house—that the work would find a buyer despite the hefty price tag.

Phillips, the perpetual underdog, fared comparatively well with a sale emphasising postwar works. Bucking the general downwards trend in the auction market, it brought in $111.2m including fees, compared with $66.9m last November. “That’s a very significant bump in a market that has contracted”, says its chief executive Ed Dolman. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s results were down compared with this time last year.

US election fails to jar art marketAll three auction houses held their sales a week later than usual to avoid a clash with the US presidential election. There was panic in the global markets the night before Donald Trump was announced the winner, but those who predicted a stock market plunge in reaction were proven wrong; US stocks rose steadily in the immediate aftermath. By comparison, the UK’s decision to leave the EU resulted in a protracted slump in the value of the pound.

Neither event, however, seemed to have any real impact on the auctions they coincided with. The UK’s vote to leave the EU was delivered during the week of Impressionist and Modern sales, while London’s post-war and contemporary summer auctions took place the following week. The lack of supply of top lots for those sales was widely acknowledged as having little to do with the referendum, and the fall in the pound’s value meant that foreign collectors benefited from discounts of up to 15%, which meant the results defied negative expectations.

This time around, some commentators ventured that the Republican party’s traditional low-tax, pro-business leanings might have actually settled investor nerves ahead of the auctions. Buyers in New York, though less frenzied than in the past two years, seemed happy to part with their cash. Brett Gorvy, Christie’s chairman and international head of post-war and contemporary art, said 55% of all bidders at the post-war and contemporary sale were American.

“I’ve been in the art market for 30 years and seen many economic issues affect all sorts of other markets but, especially in times of political and economic uncertainty, a Monet will always be a Monet,” Pylkkänen says. While this may be true, ever-greater efforts are being made to foster bidders from all corners of the globe. “Clients from 33 and 41 countries bid in our Impressionist and Modern and post-war and contemporary sales, respectively”, Pylkkänen says. “We’ve worked hard to globalise the market over the past five years”. To this end, the house organised an exhibition of its 11 evening sale works by Picasso in its new headquarters in Beijing—the first Picasso exhibition in mainland China. Sotheby’s, also saw increased participation from Asia in its sales.

Chinese bidding has become so important to the three houses that they have rescheduled their early February sales in London to avoid clashing with Chinese New Year, moving them to the last week of February and the first week of March.

Guarantee tactics are a-changin’This season guarantees seemed to vary more widely than in seasons past. Of the top ten lots in Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sale, just one carried a guarantee; the head of the department, Brooke Lampley, notes that a number of sellers turned them down. This compares with three of the top ten performers at Sotheby’s in the same category, including Edvard Munch’s Girls on the Bridge (1902), which appeared to sell on a single phone bid, presumably to its third-party backer. Every single lot in the top ten of the house’s contemporary art evening auction was guaranteed in one way or another. Overall, 25 of the 50 top lots across the five sales carried some kind of guarantee.

The head of Christie’s contemporary evening sale, Sara Friedlander, said the house was “thinking more carefully than ever before about our guarantees” in a market that has lost its “frothiness”. Nineteen lots across Christie’s two evening sales were guaranteed, but only four of those by the house.

“Anyone can buy anything”, Friedlander says, referring to the fact that guarantees essentially pre-sell objects. “The more interesting strategy is: how do you price something correctly, how do you put the right things together, bring the right things to market with material that is fresh and will capture the attention of buyers?”

Although Sotheby’s was burned by the hefty $500m guarantee on the collection of former chairman A. Alfred Taubman last year, the house deployed the tactic to win the season’s only major collection, that of Steven and Ann Ames, presented as the first 25 lots of its contemporary evening sale. This time the decision paid off, reaping $122.7m of the sale’s $276.7m total with premium.

“When they signed that collection in the summer it was very hard for the auction houses to get material”, the dealer David Nisinson said after the sale. “People were nervous and sellers didn’t know how the autumn was going to be, they didn’t want to take on the uncertainties: Brexit, the election, etcetera. They probably did a good deal and it guaranteed them a season because they could build around it”.

Hammer totals for all five sales tended toward the low estimates, but with strong sell-through rates, which implied low reserves. Other evidence supported this idea: Jussi Pylkkänen announced the reserve price for at least 13 of the 61 lots on offer at the Christie’s post-war sale, to garner bids. Phillips let a Joe Bradley painting, Frankenstein (2010), go for around half its low estimate.

All this implies that guarantees are being used strategically this season only as competition for certain lots, while the houses are trying to grow their margins.

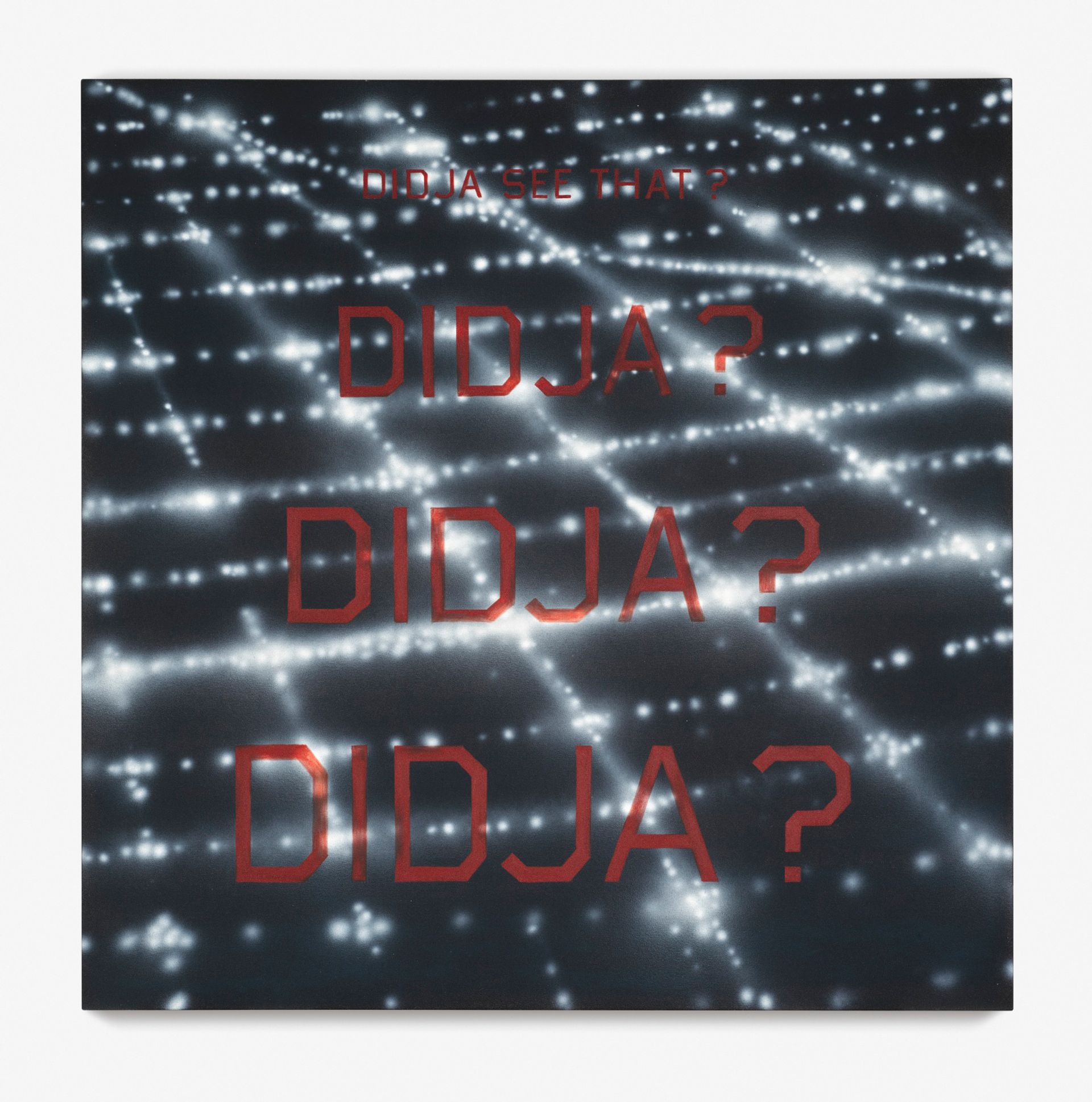

What’s up with Ruscha?This season saw four works by Ed Ruscha come up at auction across the three houses. Three of the works failed to sell, and the last one, Didja? (1987), sold at Sotheby’s with one bidder in the room for only $50,000 above its low estimate of $2.55m. That bid was irrevocable and was added at the last minute. “He’s had a rough week so I can see why,” The Wall Street Journal’s Kelly Crow tweeted when the auctioneer Oliver Barker announced it as an addition to the evening’s irrevocable bids.

Rough, perhaps, but not necessarily “OOF-worthy”. The two Ruschas at Christie’s, Truth (1973) and Point Blank (1988), were each priced at $4m to $6m—rather optimistic, considering only three of the artist’s works have ever sold for more than $5m at auction. His record, set at by the house in November 2014, stands at $30.4m, but that piece was from his earlier, and much better-known, series of yellow stylised fonts on a deep blue background (similar to his famous work OOF, from 1962). None of the November offerings could equal it; the Ruscha lot at Phillips, Peas, Asparagus, 1991, carried a more modest estimate of $600,000-$800,000 and was bought in.

None of this suggests anything ill in the market of Ed Ruscha, merely that these consignors were only open to selling if their works could fetch unprecedented, or at least unusually high, prices. Perhaps they took a gamble on the interest generated by the major Ruscha show that opened at San Francisco’s de Young Museum this autumn. If so, the bet didn’t pay off, and had Sotheby’s scrambling to save face.

Behind the prices: our selection

László Moholy-Nagy, EM 1 (Telephonbild) (1923)

Sold at Sotheby’s, 14 November, for $5.2m ($6.1m with fees;

est $3m-$4m)

In the Impressionist and Modern auction category, which is characterised by scarcity of supply, opportunities such as this do not come along every auction season. New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) saw its chance and placed the winning bid for Moholy-Nagy’s EM 1 (Telephonbild) (1923) through Mathias Rastorfer, the chief executive of Galerie Gmurzynska. “We have long aspired to add the third of Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Pictures to the two we have owned for many years,” said the museum’s director, Glenn Lowry, in a press release. The artist conceived the work in 1922 and executed it the following year by describing and ordering the picture on the phone from a sign factory, revealing his interest in industrial technology as a means of making art.

Giuseppe Gallo, Untitled (2011)

Sold at Christie’s, 15 November, for $300,000 ($367,500 with fees; est $40,000-$60,000)

Relatively late into the Christie’s post-war sale, an untitled work by Giuseppe Gallo from 2011 hammered for ten times its opening bid, with three phone bidders and three more in the room. The oil, acrylic and encaustic on board work was a surprise hit from the collection of Chiara and Francesco Carraro, and the most contested piece of the auction by far. Lot 36 took many at Christie’s by surprise as well, even if recent sales in London in the past few years have shown a hunger for this sort of work. “The Italian market is very strong, and the reality is that it’s full of good painters that are still undiscovered,” the auctioneer Jussi Pylkkänen said of the work.

Carmen Herrera, Cerulean (1965)

Sold at Phillips, 16 November, for $800,000 ($970,000 with fees;

est $600,000-$800,000)

One of the success stories this autumn was written at the start of the Phillips auction, which kicked off with a strong, deeply hued work by Carmen Herrera. The work set a new record for the 101-year-old artist (whose exhibition Lines of Sight is on view at the Whitney Museum through 2 January, 2017) when it hammered for $800,000, or $970,000 with buyer’s fees, doubling the previous record. Another work by the Brazilian artist Mira Schendel sold for the same amount, scoring another record for a Latin American female artist. The prices reflect increasing institutitional interest in such artists, and Phillips’s deputy chairman, Americas, August Uribe, credited the Herrera’s success to its inclusion in a broader context. “Had this painting been offered in the context of a Latin American sale, the buyer never would have seen it,” he said. “The catalogue would never have come across his desk.”