Visitors to this year’s Design Miami fair (until 4 December) are due to be welcomed by the world’s largest 3D-printed object: a lattice-like pavilion made from biodegradable bamboo filament, designed by the New York-based firm SHoP Architects. The commission, called Flotsam & Jetsam (2016), comes as part of the fair’s third annual Visionary Award, presented in co-operation with the Italian watchmakers Officine Panerai, recognising SHoP for its “evocative architecture, philanthropic initiatives, sustainable development and innovative practices”, according to a press release. After its unveiling at Design Miami, the pavilion—which resembles scaffolding and honeycomb structures built by tiny, industrious creatures—is due to be reinstalled next year at the Jungle Plaza in the Design District by the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, where it will host educational programmes and performances. Gregg Pasquarelli, one of the five principals of SHoP Architects, spoke to us about the project.

The Art Newspaper: You won the MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program competition in 2000, and constructed the Dunescape pavilion at the museum. Did that experience influenced this commission?

Gregg Pasquarelli: That was the first project that put us on the map. There’s an incredible amount of things that we learned from building that pavilion—rethinking drawing as architects, using materials, connection joints, the notion of thickness and so on. There’s a direct lineage from that pavilion to a project like the Barclays Center [a sports and entertainment stadium in Brooklyn], ten years later. We learned so much in that little, tiny $50,000 pavilion that ended up being the driving force behind a $1bn arena as well as the Flotsam & Jetsam project. We were interested in thinking—well, it’s 15 years later, how would we create a pavilion now?

Most of your current and recent projects are large-scale residential and mixed-used buildings. How does that intersect with a small-scale project like this?

Pavilions are an interesting kind of typology for architects because buildings take a long time, right? So you might have an idea and you might even go through a couple of years of design and time to get it approved, financed, constructed and built. Your typical project can take anywhere from five to ten years. We have 22 projects under construction right now around the world. So the idea that we could design something over a summer and it would be built by Thanksgiving was kind of fun.

What inspired the design?

There was a clear idea about designing something iconic but functional, as well as designing a pavilion in Miami that will front a New York art show. There are the obvious visual cues but also an entryway, seating area and a bar in the middle; that’s our favourite part. We were thinking about Miami: the ocean, sand dunes and sea creatures like jellyfish. Those very organic forms became things that we were interested in playing with, but we wondered how to produce it and what kind of research we could do to make this organic form into a structure.

How did you realise the project?

We worked with two companies: Branch Technology based in Chattanooga, Tennessee and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), which produced three-dimensionally printed bamboo. We thought that could be an nice intersection between furniture and art. ORNL actually broke the Guinness World Record for the largest solid 3D-printed structure earlier this year [when it created a tool to be used for building Boeing jets], so they are breaking their own record with this pavilion.

How does the 3D printing process work?

Three robots work to print it in sections that are almost 50lb each, with around a 5/8-inch thickness—fairly lightweight but strong. The printing process is like squeezing a tube of toothpaste. The bamboo carbon fibre squirts out, but in less than a second it goes from a liquid to a solid; it literally prints in the air. The fibre comes out white but you can paint it any colour. We’ve painted it a beautiful metallic copper colour, which will be fantastic in the Miami sunlight.

How large is the structure?

The entire pavilion is basically the size of a New York City block—200ft by 100ft. I think no one realises how big that actually is. People will be able to occupy it.

What were the challenges?

We had to size the bar to make sure it could support 1,000 champagne glasses.

From courtyard to arena

Dunescape at MoMA PS1 (2000)

In 2000, SHoP was selected as the winner of the Young Architects Program, an annual competition organised by the Museum of Modern Art and the PS1 contemporary art centre that gives emerging architects the opportunity to build projects in the MoMA PS1 courtyard in Long Island City. Built in time for the museum’s Warm Up summer series of concerts and events, ShOP’s 12,000 sq. ft pavilion included a functional pool, water mists, and lounging and sunbathing areas.

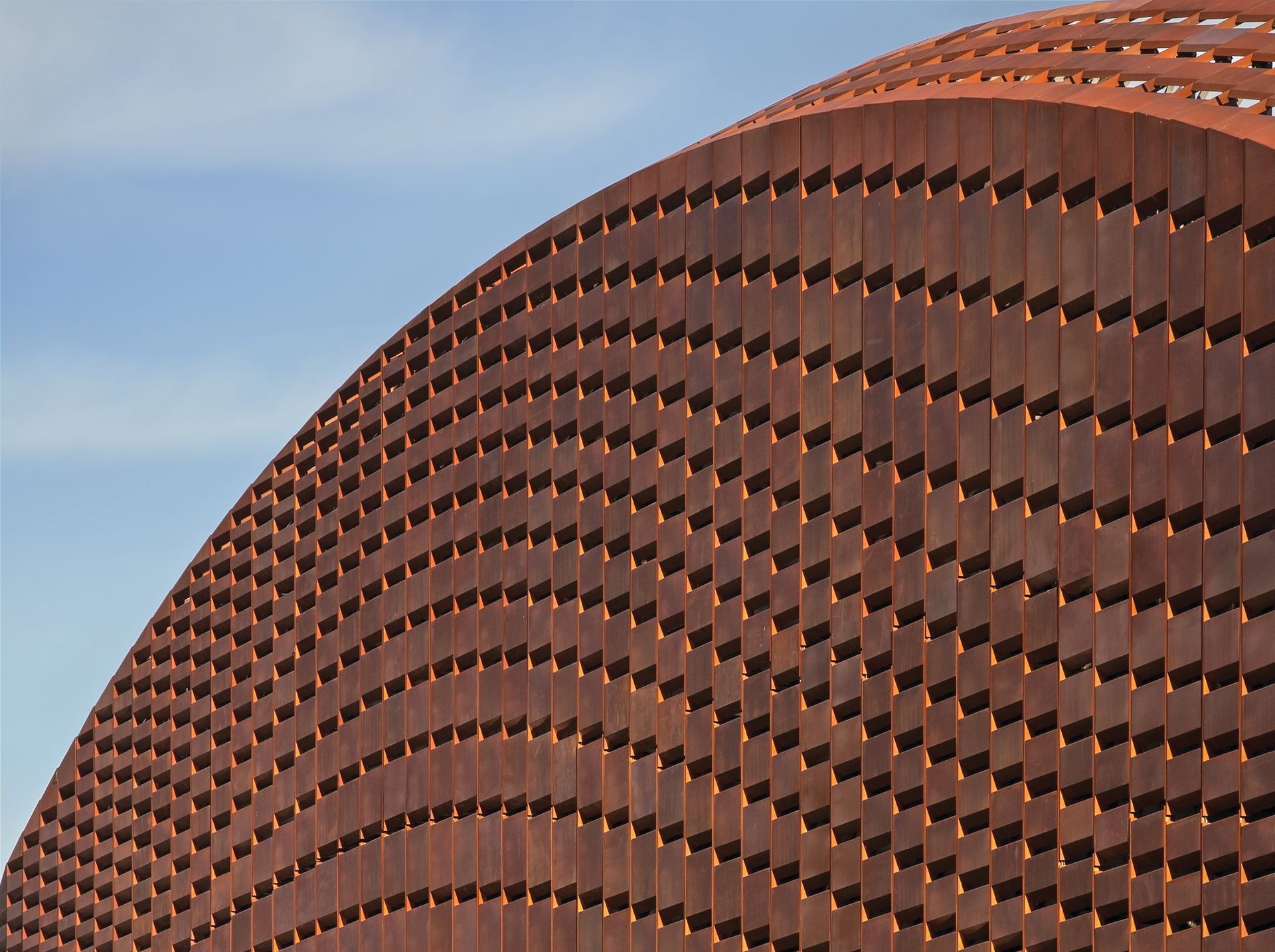

Barclays Center (2012)

The 18,000-seat sports and music arena, home of the Brooklyn Nets basketball team, faced significant delays, resistance from neighbours and financial hurdles throughout its planning, including an ambitious early design by the starchitect Frank Gehry that was almost entirely scrapped as the budget soared, to be replaced by a more functional plan by the architects Ellerbe Becket/Aecom. SHoP was hired by the developer Bruce Ratner to finish the project, and they created an open, rust-coloured pre-weathered steel exoskeleton that wraps around the building, including new concourses and seating.

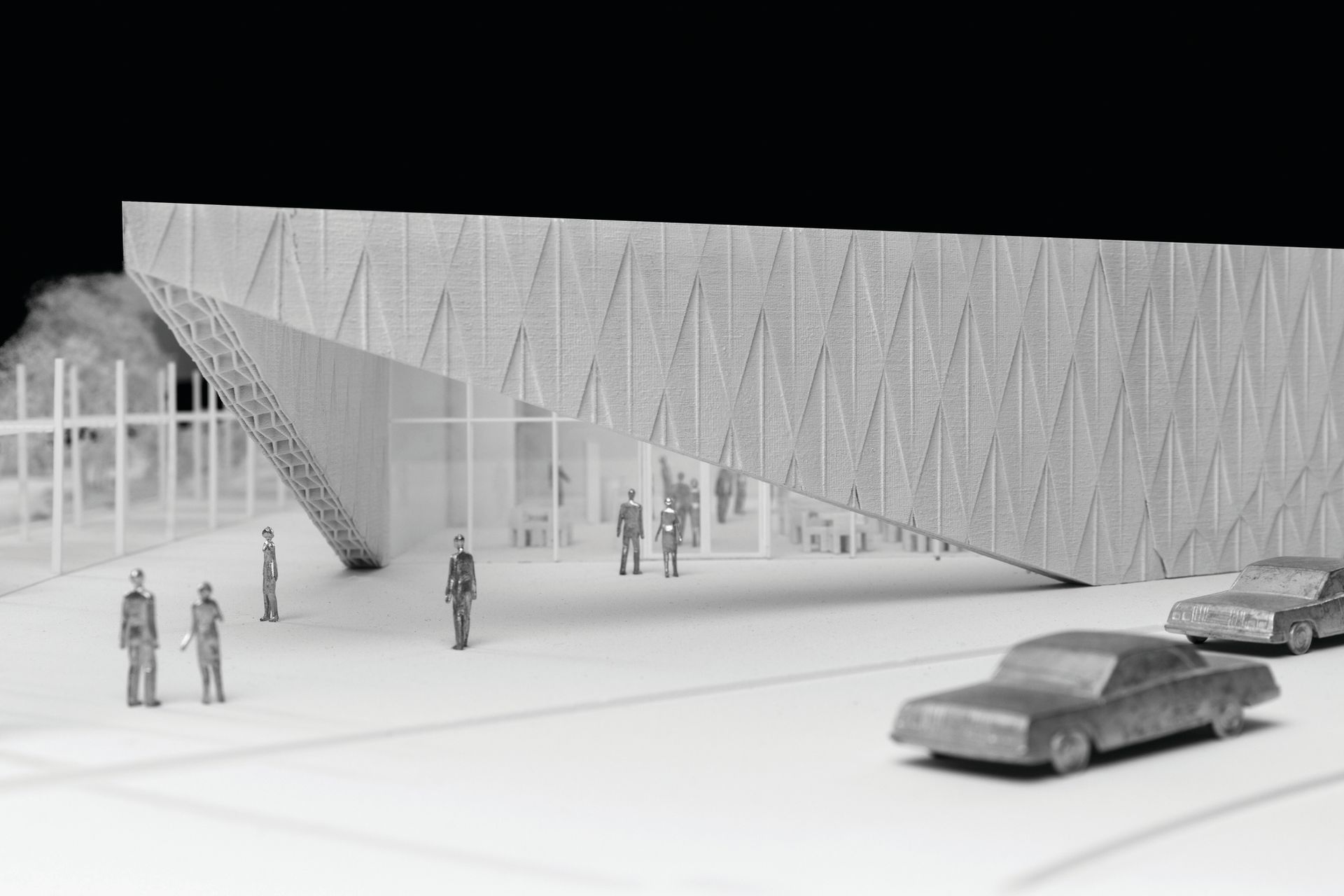

SITE Santa Fe (in progress)

SHoP was contracted to renovate and expand the biennial’s permanent home in New Mexico by 15,000 sq. ft. Some of the key features of the design include the SITElab exhibition space—a dedicated gallery for large-scale and site-specific works—a new lecture and events space, a sculpture court and a 1,825 sq ft. sky mezzanine that will include a dining area with views of the city. The project broke ground in August and is due to be completed next summer.