When the industrialist James Deering bought 180 acres of seaside land in Miami in 1912 to build a winter home, the south Florida city was far from fashionable. “Miami at that time was like a frontier,” says Gina Wouters, the curator of the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, an extravagant mansion modelled after an 18th-century Italian villa that is now a National Historic Landmark. Most of Deering’s wealthy peers were building their Florida snowbird homes further north in Palm Beach, Wouters says. “There was no precedent [in the area] for this grandeur.”

But Deering had a vision, and on Christmas Day 1916, he and his guests—all dressed as Italian peasants—celebrated the opening of his new home, designed by Paul Chalfin, Francis Burrall Hoffman and Diego Suarez. It had 34 rooms decked out with contemporary American art and a mixture of European antiques, and ten acres of formal pleasure gardens, dotted with follies.

Deering was no purist in his approach to collecting art and decorative objects, or how it was displayed at Vizcaya, says Wouters. “It was definitely created as a home for enjoyment, not as a museum to house [the collection],” she says. The estate eventually became a museum in 1935 and retains much of Deering’s original furnishings.

To mark its 100th anniversary this year, Vizcaya has commissioned a series of installations from 11 Miami-based artists that aim to re-create or re-imagine elements of the historic estate in a show organised by Wouters, titled Lost Spaces and Stories of Vizcaya (until October 2017). Amanda Keeling has made a neon light installation of a Latin quote on the east façade of the main house that reads: “Take the gifts of this hour. Put serious things aside.” There is little documentation about Deering’s pleasurable life at Vizcaya, and even less on the servants who lived there year-round, so the artist David Rohn made 16 portraits of former staff, which are hung throughout the rooms—“the most provocative” of the works, Wouters says.

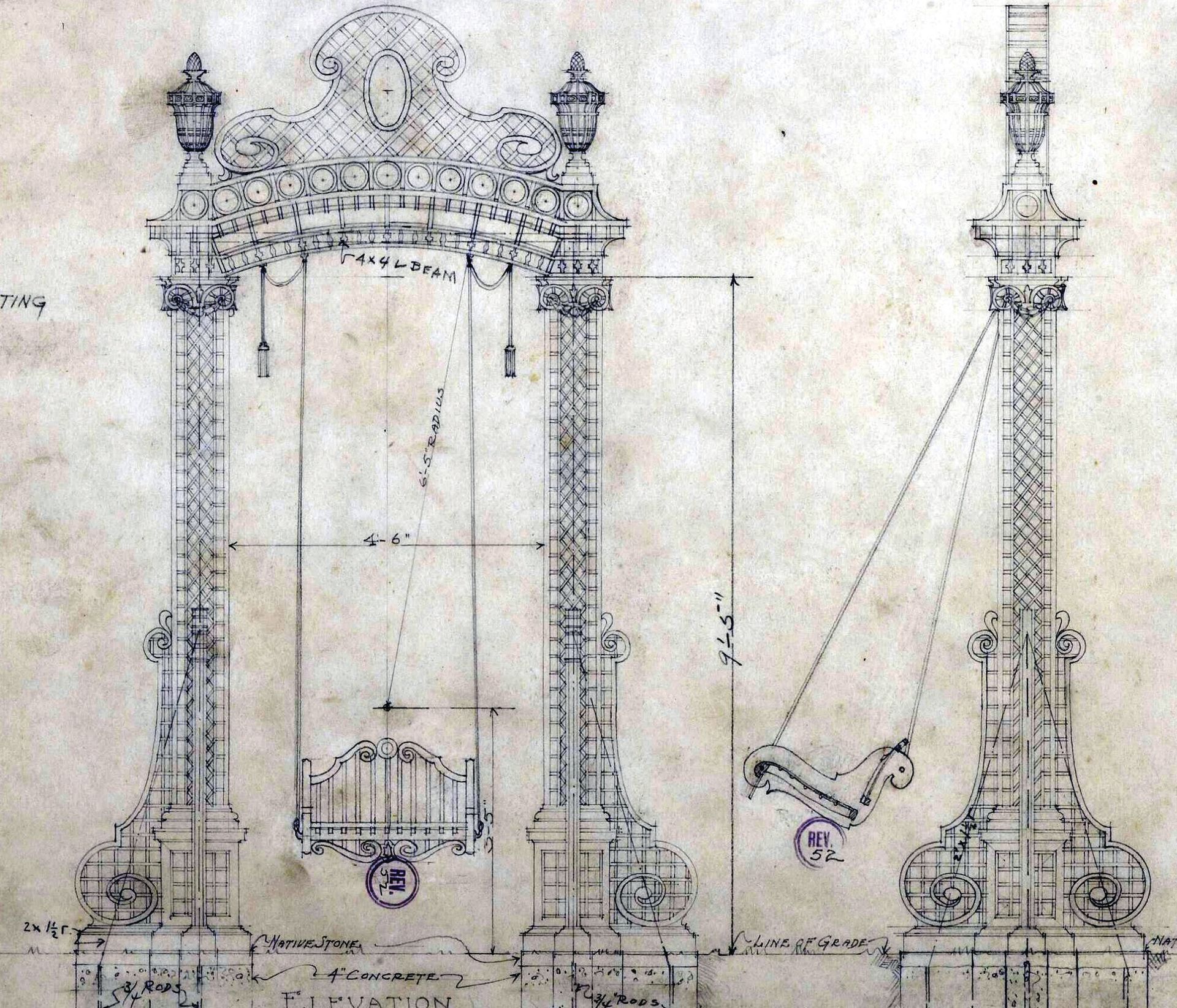

The construction and materials of the home are very well documented, though, right down to the Tiffany hardware used for an intricate and playful latticework swing in the garden—a nod to the Rococo exuberance of Fragonard’s painting The Swing (around 1767)—which was unfortunately destroyed in the 1926 hurricane. Wouters was very disappointed that no compelling proposals emerged to re-imagine this lost bit of Vizcaya, but hopes that the structure will eventually be permanently re-created, “as it was”.

1. East front

Deering wanted the villa to be seen and approached from the water, so the Biscayne Bay-facing east façade is the most monumental.

2. The swing

A drawing of the swing built out of Tiffany-made parts that previously stood in the Vizcaya’s Fountain Garden.

3. Moat

Workers digging a moat around Vizcaya during the villa’s construction. Since the native coral stone is very porous, it did not retain water and was a “failure”, Wouters says. It was “a fabrication like almost everything else at Vizcaya—an artifice”.

4. J’ai Dit

Inside the East Loggia overlooking the gardens is Amanda Keeley’s J’ai Dit (2016) neon installation, which translates a Latin motto by the Roman poet Horace on the sundial above the balcony on Vizcaya’s east façade. The light work reads: “Take the gifts of this hour. Put serious things aside.”

5. East Loggia

How the East Loggia looked around 1926, several years after it had been finished. The galleon suspended from the ceiling is a recurring motif in the villa.

6. The Barge

A boating party approaches Vizcaya’s Barge—a massive aquatic sculpture designed by Sterling Calder, the father of the mobile designer Alexander Calder—some time around 1920.

7. Tea House

The Venetian-style Tea House in the villa’s gardens.