At 88 years old, Julio Le Parc is having a moment. The artist is enjoying his first solo US museum show at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (Pamm). The exhibition, Julio Le Parc: Form into Action (until 19 March 2017), is the culmination of a banner year for the kinetic and Op Art pioneer. Le Parc has had two solo shows in New York this autumn: one at Galerie Perrotin, and another at Galeria Nara Roesler (Julio Le Parc, 1959-70, until 17 December). Nara Roesler is also showing his work at Art Basel in Miami Beach this week.

The artist represented his native Argentina at the Venice Biennale in 1966, where he was awarded the Grand International Prize for Painting. The collector and art historian Estrellita Brodsky, who organised the Pamm show, says: “Le Parc is a pioneer in the use of light and movement in art, and explored ideas of participation long before relational aesthetics became popular. Nevertheless, Le Parc is still relatively unknown in the US.”

He is unlikely to remain that way for much longer. The Pamm exhibition brings together Le Parc’s paintings, lightboxes and large-scale motorised light installations, as well as works he made with the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (Grav), a collective he co-founded after moving to Paris in 1958. Visitors will be encouraged to let loose in a game room filled with his interactive works, from ping pong tables to seats that bounce. We spoke with Le Parc in New York earlier this month.

The Art Newspaper: The curator Estrellita Brodsky says she believes the utopian aspect of kineticism has often been overlooked. Can you describe the social or political significance of your work?

Le Parc: The social aspect was the idea of seeing how, as artists, we could seek to transform the status quo. That’s why most of the things we began to do were directly connected with the public, without intermediaries. It was better if the people were less ‘conditioned’—that they were not dependent on the mindset of the artist, on artists’ prices, or on criteria already pre-established by critics about how to appreciate contemporary art.

Why was the motto of Grav, the collective you were part of in Paris in the 1960s, “Il est interdit de ne pas participer” (“it is forbidden not to take part”)?

In our manifesto, we wrote that, if there is to be a transformation in contemporary art, the viewer must not be left out of it. Because in that moment—and even now—the viewer didn’t count for anything. The viewer is never taken into account in the evaluation of contemporary art. They don’t have the means of expressing themselves, [unlike] people with money, who can pay and give a monetary value to a painting.

Did the museums in Paris inspire you when you first arrived from Buenos Aires in 1958?

[I went to] the Louvre, the Musée d’Art Moderne [de la Ville de Paris], I visited the important galleries for reference. Then, it was done. I didn’t have any need to return—once I had seen it, I absorbed it. All of my time and attention was on what I myself was doing. It was no longer important to look at others.

Some of the works in the Pamm show are original, while others are re-creations. Two curators who have worked with you said that you reject the ‘fetishism’ of the work of art. Why?

For me, the way a work connects with the public is more important than the material side of it. An object from the 1960s can be remade with the same idea. It’s the idea [that counts], not the material.

Do you have a favourite work out of your oeuvre?

Do you have brothers or sisters?

Yes, an older brother.

And who is your mother’s favourite?

Me, I think—no, I’m kidding, she always says she doesn’t have a favourite.

Voilà. I don’t have a favourite either among my works, just like parents don’t have a favourite child.

So in the exhibition at Pamm, is there one work that you feel is particularly important for people to see?

But that’s the same question [as before]! You’re cheating, you’re cheating!

What do you hope audiences take away from the show?

I would be happy if, when leaving the exhibition, visitors feel a bit more optimistic, more confident in themselves, more peaceful, more relaxed, empowered to confront problems with more energy. For me, it’s enough simply if people are left more optimistic about life and the people around them.

An artist in three acts Julio Le Parc: Form into Action brings together more than 100 works by the artist. The show, organised by the collector and art historian Estrellita Brodsky in close collaboration with Le Parc, is arranged thematically rather than chronologically. Here are three highlights from formative moments in the artist’s career.

From two to three dimensions

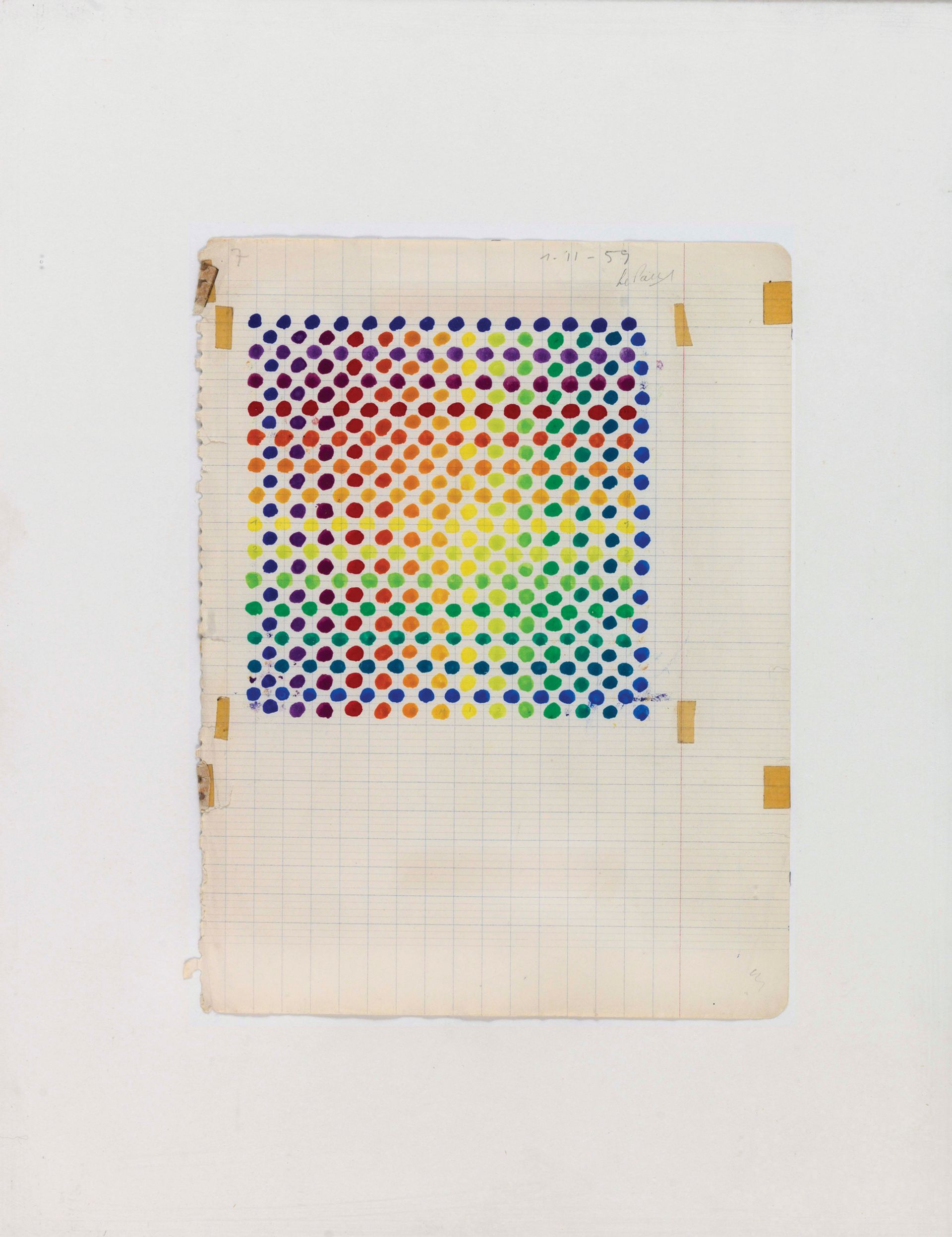

Projet couleur n° 5 (Colour Project n° 5, 1959)

The first section of the exhibition uses Le Parc’s paintings to trace the evolution of his experiments with form and colour from two dimensions to three. In early gouache works on paper, such as this example from 1959, he refined the palette he would later use in the 1960s lightboxes.

Light show

Continuel-lumière mobile (Continuous-light mobile, 1960/2013)

The disorienting light installations that Le Parc showed with the collective Grav at the 1963 Paris Biennale are spread across three rooms at Pamm. Brodsky says that this work from 1960 extends “into the viewer’s space” and “becomes an environment”, flooding the space with light.

Illusion

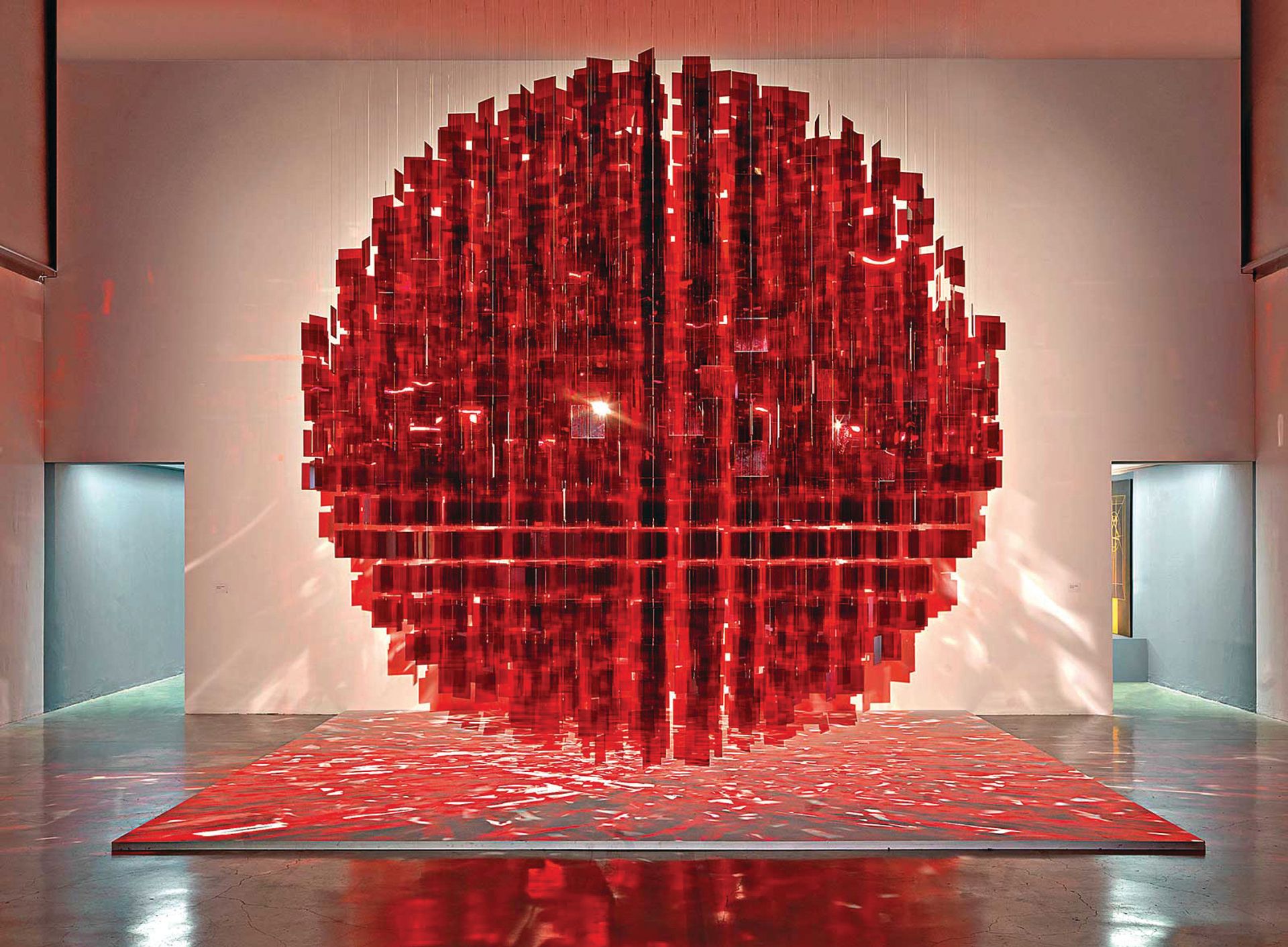

Sphère Rouge (red sphere, 2001-12)

The show ends on a bold note with this large suspended work, which is more than three metres in diameter. Although it appears to be spherical, it is actually made of small, suspended Plexiglas squares.

From the archives

During the 1960s, Le Parc was a member of the Grav collective, which staged public interventions such as this one, called Une Journée dans la Rue (Day in the Street). On 19 April 1966, the collective invited passers-by to walk on blocks of wood placed on the street in Paris.