Seeing Bruce Conner's career survey, It's All True, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art brought back to me the sense of urgency, relentlessness and wry confrontation that I experienced 16 years ago when I interviewed Conner, who died in 2008.

He and I had met in passing a few times on the San Francisco art scene, but never had an occasion for sustained conversation until the approach of his earlier retrospective, 2000 BC: The Bruce Conner Story, Part II, at San Francisco's De Young Museum.

Under pressure from the congenital liver ailment that eventually took his life, Conner had told me by phone that he typically felt his energy spent by midday. I would have to meet him at home in the city at 9AM. Facing a tight newspaper deadline, I decided to keyboard our conversation directly into my laptop, so I could edit it in a hurry.

At first, Conner seemed subdued, but he soon relaxed and quickened. "When asked a question, I tend to answer with a story," he said. And his answers to my queries began to tumble into a hurtling monologue. He pinballed from topic to topic, from his presciently impish attitude toward authorship to the insanity of American militarism (especially of nuclear weapons); from his work habits and techniques, curtailed by his weakening health, to his ambivalence toward a museum retrospective and art world conduct generally. (Frustrated by the expectation that he cultivate a career, Conner once tendered his own obituary to an art magazine.)

Conner began his authorial mischief long before Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman or Richard Prince came on the scene. "One myth still being promoted," he said in 2000, "is that the artist's work expresses his innermost self". People still prefer to believe in a "one-to-one correspondence" between an artist's thoughts and his work, he complained, "rather than think of the artist on the model of a writer or an actor, someone who works with narrative, irony, changing voices."

At SFMoMA, exhibition labels attribute some late, eye-straining abstract drawings to "Anonymous" or "Anonymouse," two of Conner's authorial disguises. "We were all anonymous artists here in the '50s" he told me, referring to friends such as Jay DeFeo (1929-1989), Wally Hedrick (1928-2003) and Joan Brown (1938-1990).

In the early 1970s, Conner made a series of Max Ernst-like collages from old engravings (displayed at SFMoMA) and presented them in Los Angeles in an exhibition titled The Dennis Hopper One-Man Show, after his actor friend, who was a wild-eyed photographer, but never made collages or prints.

The SFMoMA exhibition, enriched here by the addition of 85 works to its first presentation at New York's Museum of Modern Art, includes assemblages, collages, paintings, prints, drawings and photograms. But the eight films that punctuate the show, playing continually, will most haunt the memories alike of visitors who have and have not seen them before.

Conner frequently relied on readymade materials, though time—no one's invention—has become the most active ingredient in the luxuriantly tacky assemblages that first made his name, such as the grandly disintegrating Spider Lady House (1959), lent by the nearby Oakland Museum of California.

That piece's materials give a fair idea of Conner's vision of just about anything as possible grist for art: wood, nylon, an ice skate, doll parts, string, costume jewellery, feathers, fur, bottle caps and wallpaper and paper on plywood.

Conner's assemblages, which can bring to mind Robert Rauschenberg's contemporaneous combines, form snarling satires of Post-war American consumer yearning and its repressed undercurrent of sleazy eroticism. In their present decrepit state, despite the light touch of scrupulous conservators, these raunchy plaques, webbed with fraying stocking nylon, evoke Dorian Gray-like portraits of corruption festering beneath the twinkling cultural amusements of America's past half century.

As a teenager growing up in Kansas, Conner saw movie house newsreel footage of an American atom bomb detonation at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. In a sense, he never recovered from the experience. "My entire history as an artist coincides with the history of the bomb," he told me. "It's coloured almost everything I've done. But I also don't see why you can't have a good time and be aware of your own mortality."

In 1976, he made Crossroads, a film composed entirely of declassified official footage of nuclear weapons testing at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, which the US military conducted and shot from numerous aerial and sea level vantage points between 1946 and 1958. Taking its title from the bomb test's code name, Conner's 37-minute film (projected wall-size here) replays the same colossal event more than 20 times at varying speeds, carefully keyed to music by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley.

Waves of shock pass like nausea through a viewer of Crossroads at first, but the greatest shock comes with the recognition that repetition hypnotically renders the world-menacing explosion first seductive, then almost sedative. Read the work as an indictment of the bomb, or of film's anesthetic power, or of our species' unacknowledged death instinct—however you see it, Crossroads proves the power of readymade imagery, gingerly handled, as nothing else in the canon has.

Other film works, staged at SFMoMA with great immediacy and little concern for sound bleed, vary starkly in impact and cultural confrontation, but all show Conner as an artist prodigiously sensitive to the power of sound and music.

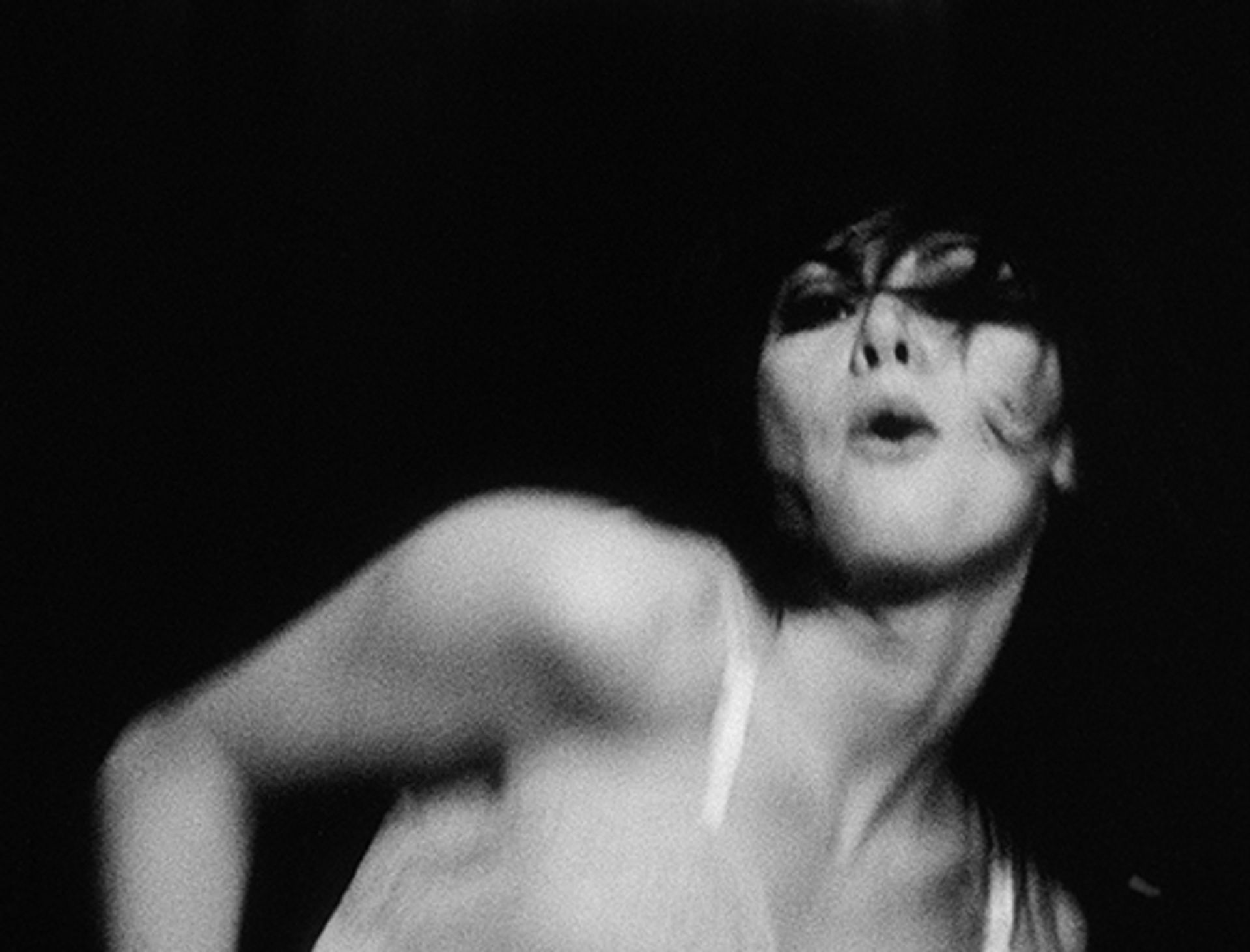

Bay Area artists of Conner's generation have long revered his defiant spirit and inventiveness. His work's apocalyptic and psychedelic qualities—epitomised by the luminous full-figure photogram self-portraits he called Angels—play well against the shrill vulgarity, social desperation and economic cruelty of current domestic and world affairs. It lends the show an uncanny timeliness. How a younger generation registers his work in a roiling 21st-century context will be fascinating to see.

A little before noon on the day of our interview, Conner rose to show me out, bright-eyed and seemingly afire with energy, while I, drained from trying to keep pace with him, could barely summon the strength to thank him properly. Attentive visitors to Bruce Conner: It's All True will emerge with a similar sense of having experienced a bracing, though punishing, encounter with a uniquely powerful and fearless creative force.

Kenneth Baker retired in 2015 after 30 years as resident art critic for The San Francisco Chronicle. He is an Art Newspaper correspondent based in San Francisco

Bruce Conner: It's All True, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, until 22 January 2017