For anyone who was around on the London art scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s, reading this book is a bit like being in an uncanny time warp. Artrage! is a forensically detailed recounting of the rise to fame of the artists who were part of what Elizabeth Fullerton refers to as the “BritArt Revolution”. On the way, we are reacquainted not just with the leading lights of the “YBAs”, such as Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas, but also with a host of names once uttered in the same breath as the post-Freeze generation, but who have long since fallen into obscurity. Readable as the book is—it is based on anecdotes and gossip culled from hundreds of hours of interviews—its main problem is that it comes across as if nothing much has happened in the 25 years or more since then.

Nowadays it is not easy to say “YBA” or “Britart” without a tinge of embarrassment, such has the critical stock of its protagonists plummeted. A few, including Lucas and the Chapman Brothers, continue to thrive, but Hirst and Emin have become virtually unmentionable to a younger generation of London-based artists, who see them as synonymous with the bloated, narcissistic excesses of what the art world has turned into since the 1990s. Today, Britart has about as much critical credibility as Blairism and Britpop. Unfortunately, Artrage! has next to nothing substantive to say about this.

Nor does failing to provide any detailed critical analysis of individual works do the artists here any great favours, since more than a few works made in London at the time still stand up. Hirst’s shark piece (1991), and his A Thousand Years, life-and-death-cycle machine (1990), along with the Medicine Cabinets series (1988-2012) testify to his uncanny capacity, at the time, to be able to transform objects into stunning 3D images. The same goes for Lucas’s Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992) and Au Naturel (1994), and Jake and Dinos Chapman’s Chapmanworld-period work.

These works certainly represented a departure from the predominantly New York, October-theory-led Newspeak into which much late-postmodern art and commentary had descended by the early 1990s; a new, much more humorous intelligence had come to challenge the dry irony of the endgamisms of the 1980s and early 1990s. For the first five years of his career, Hirst was still very much part of this, but then ascended into the new international asset-class art-world stratosphere that has emerged since the 1990s.

Devoid of any proper art-critical work, Artrage! leaves us unable to distinguish the early Hirst from the later one, and the same goes for trying to disentangle the few quality YBA works from the vast majority of kitsch that the scene can be seen in hindsight to have generated. All this testifies to the cogency of art historian and critic Hal Foster when he stated: “History without critique is inert, criticism without history is aimless.”

Another vital dimension of the YBA scene is in need of timely reappraisal: the way it stands as a kind of anti-monument to an art world it displaced, as one of the many anecdotes reminds us, an art world reminiscent of a “discreet and exclusive gentleman’s club” that left younger artists “wondering how long they’d have to wait until Howard Hodgkin died” before they had a chance of a look-in. London became genuinely exciting in the 1990s because it offered new opportunities for young artists (who were able to take advantage of them): cheap rents for studios and flats, a new, expanded class-profile in the art world and a host of new artist-run spaces to show new work.

For a while, it was, in fact, in these independent spaces where all the action was perceived to be happening. Today, nothing could be further from the case. Artrage!, with its wealth of reminiscences, is quite good on this, but without any proper critical contextualisation it ends up being too repetitive of the long evaporated mythology that built up around the DIY dimension of the YBAs.

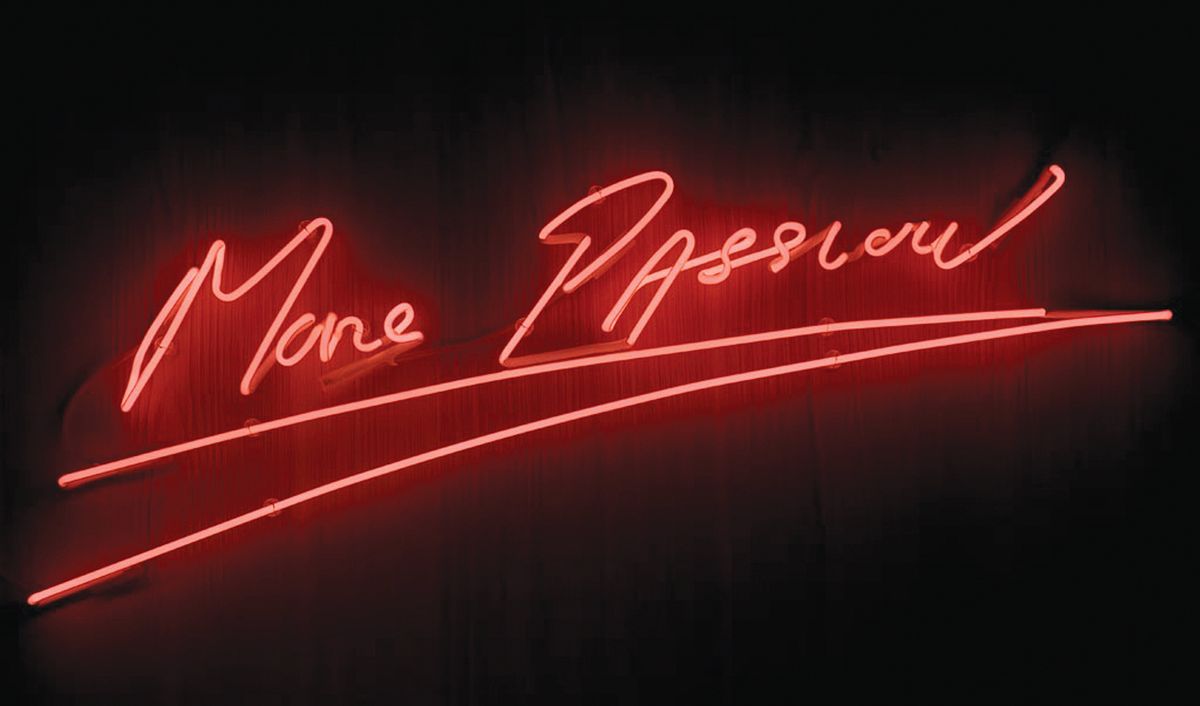

One story it curiously omits to mention is Emin’s broadcast in 2010 of her pride at having voted Tory in that year’s election. Another is how a neon piece of hers took pride of place for David Cameron on a landing at the top of the main staircase at 10 Downing Street.

Robert Garnett is a London-based writer and critic, and a lecturer in art and art theory at the University of Reading. He is currently completing a book on humour versus irony in art since the 1980s

Artrage! The Story of the BritArt Revolution

Elizabeth Fullerton

Thames & Hudson, 288pp, £24.95 (hb)