Mike Kelley had no way of predicting the incredible controversies of the 2016 US presidential election, but he did create a powerful platform for viewing it. His Mobile Homestead project, which offers an alternative sort of community centre on the grounds of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, has become the scene of boisterous debate-watching parties, with an election party due to take place on 8 November. Inside the structure, which is modelled on the working-class ranch house outside Detroit in which the late artist grew up, an election-themed show fills the rooms and garage. It’s Your Party (until 1 January 2017) is an exhibition of presidential campaign memorabilia from the vast collection of Morry “the Button Man” Greener.

The museum’s director, Elysia Borowy-Reeder, says that it plans to take Mobile Homestead back on the road in 2017—the venues have not yet been confirmed—“to do a politically nuanced exhibition that deals with water”. She says: “While some states are facing a drought, Michigan is the biggest ‘fresh coast state’, but has issues like what happened in Flint,” referring to the discovery last year that the city’s drinking water was contaminated with lead. In 2018, the museum is planning a show (the details have yet to be announced) that will focus on Kelley’s influence on other artists.

Artists’ legacy Mobile Homestead is one of a growing number of projects and exhibitions across the US supported by the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, which the artist founded in 2007, five years before his death. This summer, the foundation announced a $100,000, two-year grant to support Mobile Homestead, and $310,000 for other projects. The foundation has also been working hard behind the scenes to organise his archives and the works of art in his estate, which is fuelling a number of gallery exhibitions.

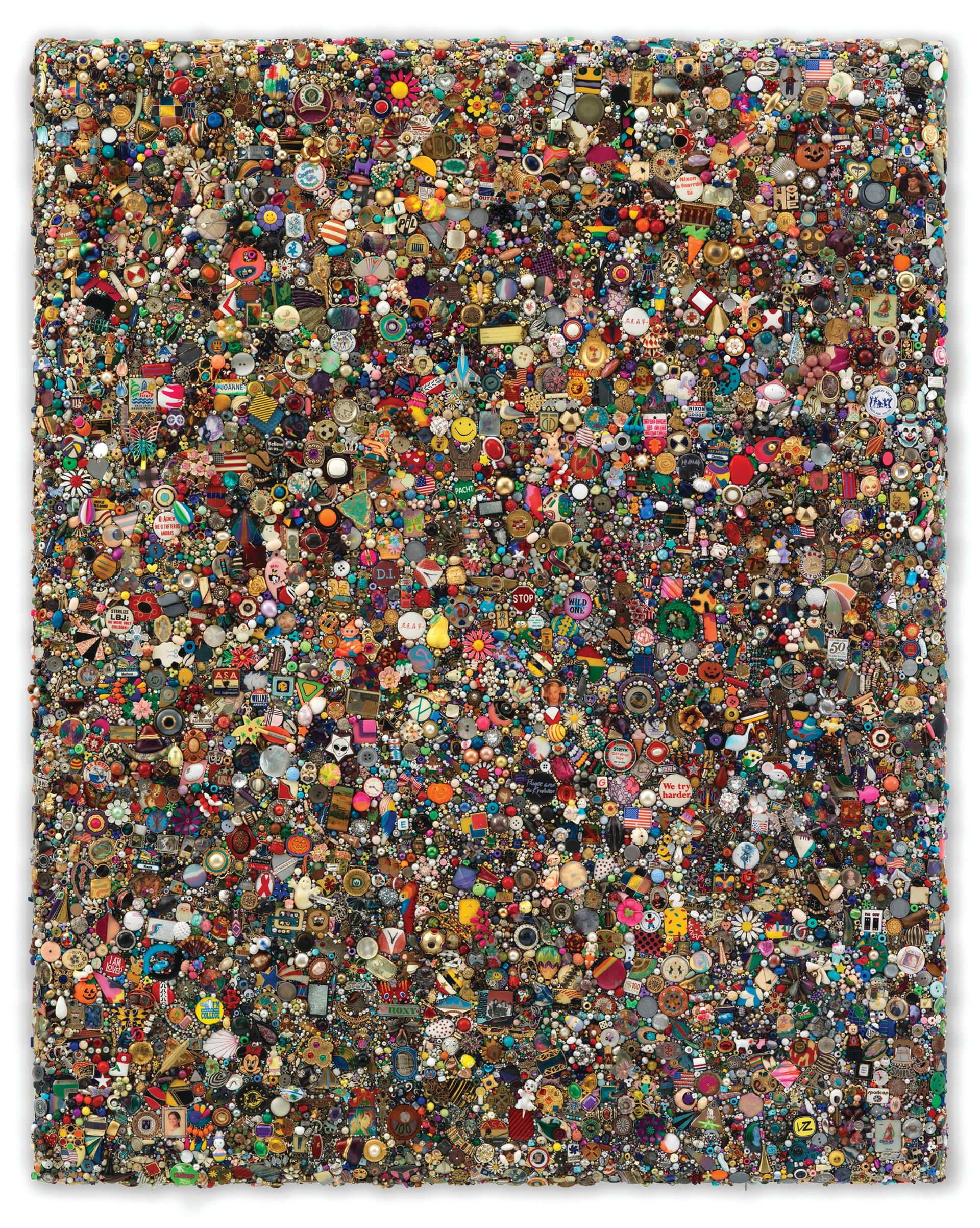

Most notably, Hauser & Wirth, which has exclusive representation of the estate, will show Kelley’s Memory Ware Flats at its 69th Street space in New York this month. These works have long been seen as his most decorative series: wood panels decorated with beads, buttons, shells and other found objects that Kenny Schachter once quipped “pass the Park Avenue test” for being easy to transport in pre-war elevators, not visually challenging and “instantly recognisable”.

But in an effort to plumb the works’ complexity, Hauser & Wirth will show them alongside related sculpture, and will publish a scholarly catalogue with an essay by Ralph Rugoff, the director of London’s Hayward Gallery. The show, Memory Ware, which opens today (until 23 December), and the book have been produced in partnership with the artist’s foundation.

Last month, Hauser & Wirth presented its first London show of the artist, Framed and Frame (until 19 November), featuring his Chinatown Wishing Well installation, a craggy mound covered with votive candles and reliquaries. And next year, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel will hold the first show dedicated to the artist’s Superman-inspired, cave-like Kandor series in Los Angeles.

Supporting artists

Group shows looking to include Kelley are also happening across the country. “I would say that the level of interest right now is very high,” says Mary Clare Stevens, who became the executive director of the foundation after working as the artist’s studio manager. “We don’t have a full list yet for the collection, but we work closely with curators to help direct them and go over what might work.”

Stevens says that the foundation issued $310,000 in grants to artists and small arts organisations this year, including a grant for Radio Imagination, a project exploring the legacy of the African-American sci-fi writer Octavia Butler through events and exhibitions.

“Mike saw his legacy as a way of supporting other artists’ work,” says Paul Schimmel, a curator who initially served on the foundation’s board and was later instrumental in helping Hauser & Wirth to gain exclusive representation of the artist’s estate. “Almost all artist foundations are begun by artists very, very late in life. The fact that Mike started this when he was in his early 50s and asked John [Welchman] and I to be directors is really unusual and speaks to his commitment to supporting other artists.”

Welchman, an art historian, continues to serve on the board, alongside the artist Jim Shaw, the arts patron Gary Cypres, the Getty Foundation’s deputy director, Joan Weinstein, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Stephanie Barron, who took Schimmel’s place as a museum expert when he stepped down to become a partner in his gallery.

Stevens did not have an update on the preparation of the archive, which the foundation’s website says will be available for consultation by researchers and scholars “in the near future”, or on the placement of works of art in museums. But she says that finding good homes for the remaining art is an important goal. “Part of our bigger plan is to make works available to a broad public, to place them in important institutions internationally,” she says.