The below excerpt is taken from the art critic and historian Barbara Rose's catalogue essay for Painting After Postmodernism, an exhibition of 16 American and Belgian painters—including Walter Darby Bannard, Larry Poons, Werner Mannaers and Joris Ghekiere—whom Rose sees as making a serious case for the continued relevance of painting in our digital age. The exhibition is on through 16 November at Vanderborght and Cinéma Galeries/the Underground in Brussels.

This exhibition intends to prove that painting as an autonomous discipline can still make fresh, convincing statements as a living, evolving and significant art form that communicates humanistic values in an increasingly inhuman, technology driven globally networked world. The idea that painting is dead, dying, or of diminishing importance is reflected in the novelties crowding commercial art fairs and the growing number of international biennials. But the idea that painting is no longer a living art is not new. Its initial mourner was the French academic artist Paul Delaroche. On seeing the first daguerreotype in 1839, he is said to have claimed, “from today, painting is dead.”

Ironically, it was a photographer who defended the capacity of painting to endure. The historic first exhibition of the Impressionist painters, held in the studio of the portrait photographer Nadar in 1874, proved that photography did not kill painting, but rather that painting could redefine itself as a viable and progressive art form by concentrating on visible brushstrokes that call attention to variable tactile surfaces whereas all photographs share a uniform, slick printed surface. Today, ambitious painting confronts an analogous situation as fast moving pixilated imagery challenges its values and practices. Available to all, and not just to the trained and educated, digital technology appropriates, recombines, and recycles images in often surprising and novel visual combinations that create flashy, momentary, instantaneously consumed images that shock and awe. But reactions to these images, no matter how striking or gut wrenching, are short lived and fugitive.

Fine art that is durable, remains in museums and collections after its authors are long gone, requires a more lasting, profound, and transformative involvement. The same year Delaroche claimed that photography would replace painting, Stendhal dedicated his great complex and layered novel The Charterhouse of Parma to “the happy few.” Today, serious artists making equally complex and layered works, requiring years of skill and training, confront the same lack of understanding that faced the Impressionists and Stendhal. In the context of electronically communicated mass culture, the face to face confrontation, and the extended amount of time required to digest, dense and multifaceted artworks are out of step with the standards of the dominant culture of instant gratification and easy entertainment. I have no idea whether in a hundred years their works will endure. This exhibition is a wager that they will.

I began to think of presenting contemporary American painters together with their Belgian counterparts when I noticed that there were artists working in both countries to reinvigorate painting by expanding its parameters, as well as by building on its foundations, with a respect for fine detail and careful craftsmanship. The issue is not whether the work is abstract or representational, but rather on the type of space being created, and on the redefinition of imagery within that space. After visiting scores of exhibitions and studios in the USA and Belgium, I found that exciting new work was based on expanding the processes of painting as a means to evoke imagery that was not a priori and schematized, but rather provocative and open to individual interpretation.

The work that particularly interested me had variable texture that defines the surface plane as a tactile experience, a respect for chance and accidental occurrences, and awareness that these required structure in order not to collapse into incoherence. The struggle to keep painting alive and moving that began with Cézanne and Manet remains a battle against cynicism and nihilism. In 1918, the year World War I ended, leaving Europe in ashes, Marcel Duchamp once again tolled the death knell of painting in Tu m’ (1918), his farewell to the medium that bored him, but continued to interest such painters as Léger, Matisse, Miró, Mondrian, and Picasso. Three years later, in the Moscow exhibition 5x5=25, Rodchenko exhibited monochrome canvases titled Pure Red Color, Pure Blue Color, and Pure Yellow Color (1921). He claimed that these were the last paintings that could be made, because they reduced the art to its essence: an uninflected plane of a single colour representing nothing but itself. “I affirmed,” he wrote, “it’s all over. Basic colours. Every plane is a plane and there is to be no representation.”

In the early 1960s, with the aim of democratizing art, “Pop” artists turned their backs on abstraction to employ familiar imagery, signs, and symbols of popular culture requiring no education to understand. The rationale that Pop Art was a critique of commodity culture quickly turned in on itself when the masses embraced its graphic imagery and simplified poster like legibility, which has more in common with the two dimensionality of printmaking and advertising art than with the complex space of painting. However, the popularity of Pop images did gain attention for painting. This changed in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, when once again it became fashionable to denounce painting as an irrelevant relic of bourgeois culture. In this climate of political correctness, museums and galleries rushed to embrace forms of “radical art” that illustrated various ideological platforms.

A further attack on painting as a form of retarded decoration was launched by literalist, anti-illusionistic Minimal Art, which unlike the vacuous, bright, and shiny surfaces of Pop Art, had a philosophical grounding in phenomenology and Gestalt psychology. Then in the highflying 1980s and 1990s, nouveau riche collectors gorged their famished appetites for garishness on Neo-Expressionist figuration, to the point of elevating graffiti as painting. With fine art clearly losing ground, and the happy few becoming ever fewer, museums, increasingly dedicated to enlarging paid attendance, and most galleries, whose purpose is profit, favoured easily consumed popular styles. The result was that the difference between high and low art was gradually but consistently erased, beginning in 1990 with the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture. Suddenly, art had a huge popular audience in New York, but the center of painting had been displaced to Berlin, where a postwar generation including artists Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Markus Lupertz, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter redefined— in contemporary terms—the painterly, expressionistic style characteristic of German art.

Their monumental painterly work, however, was disregarded by the dominant American art critic of the post-World War II era, Clement Greenberg, the hero of a generation of critics trained as art historians in the leading universities of the USA. The importance of Greenberg as a tastemaker cannot be overstated. A brilliant writer and a powerful, domineering personality, Greenberg’s lean and elegant style immediately seduced readers. Among his first essays, Towards a Newer Laocoon, published in the Partisan Review in May 1941, argued for the supremacy of abstract art as a means to maintain the purity of painting by distinguishing itself from the other arts.

Isolating the unique properties of a medium to preserve its purity became central to Greenberg’s critical judgments. The struggle of the avant-garde thus became the fight to escape from literary subject matter. In his reviews in The Nation, for which he wrote weekly from 1942 to 1949, he insisted that in order to remain “pure” and uncompromised, painting must be addressed to eyesight alone. Subject matter was a primary distraction, but so was any inference of spatiality. Toward this end, all traces of the hand were to be expunged in favour of instantaneous retinal impact.

For Greenberg, Jackson Pollock’s poured and dribbled “allover” paintings created a disembodied, optical web experienced exclusively in visual terms. Rejecting the gestural style of Willem de Kooning, trained in Amsterdam’s highly reputed Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten to appreciate the painterly styles of Rembrandt and Rubens, Greenberg hailed Pollock as the master of the future, not the past. For the next fifty years, Greenberg pursued this argument, convincing his growing group of admirers of its ineluctable truth.

In Europe, on the other hand, especially in Belgium and the Netherlands, the example of painterly painting based on visible brushwork was part of their own historic tradition, which continued to be taught in the fine art academies at a time when Americans were obsessed with newness. However, painting was also being attacked in Flanders by the Belgian art historian Jan Hoet, who like Greenberg, was a failed painter attracted to power strategies. If Greenberg was called “the art czar,” Hoet was known as “the pope of art,” whose mission was to marginalize paintings in favour of installations and new technological media.

Obviously, as an American, I am more familiar with Greenberg’s interpretation of Modernism than I am with the texts read by Belgian artists. My impression, however, is that in Belgium—due to its rich and deep-rooted heritage in the art of painting—artists continued to be educated in practical skills, even when they were rejected by cultural impresarios like Hoet, who dominated recent Belgian art as much as Greenberg served as a gatekeeper to success for English speaking artists.

In the USA, artists were not scorned as painters, but rather as heretics from Greenbergian dogma. In Belgium, Hoet, easily as powerful a tastemaker as Greenberg, used his political connections to expunge painting altogether in favour of conceptual installations and technology based media drawn from the distant corners of the world without respect for quality or durability. Hoet concentrated on actions, not words, making his mark in a newly prosperous Europe, whereas Greenberg made his arguments in print and in lectures throughout the English-speaking world.

In 1964, Greenberg organised the exhibition Post Painterly Painting at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, insisting that what was new about recent painting was its emphasis on brilliant colour over physical gesture. The artists selected, according to Greenberg, shunned thick paint and tactile effects in the interests of optical clarity. It is true that following Pollock, many younger painters abandoned conventional paintbrushes, which emphasized the tactile stroke. Included in the show, Walter Darby Bannard was among the first to renounce the paintbrush in favour of squeegees, rakes, and brooms, which he used to apply mixed media and gels that thickened the surface to literal relief.

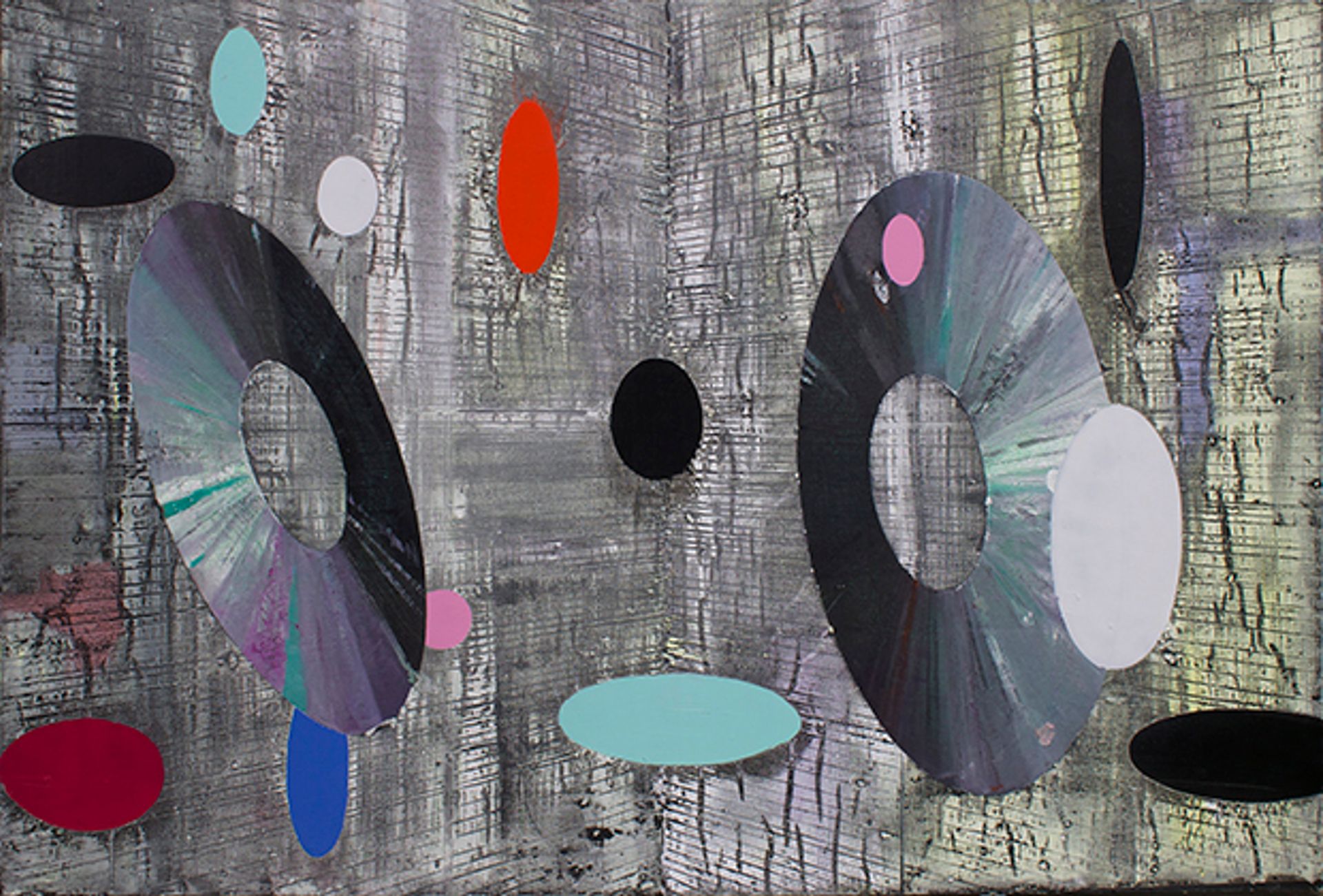

Larry Poons, whose early paintings of highly coloured stained fields punctuated by dots and ellipses of contrasting hues that corresponded to Greenberg’s criteria, declined to be included. Originally a student of composition at The Boston Conservatory of Music, Poons began painting as a geometric abstractionist with compositions, like those of Ed Moses’ early works, which recall those of the Fleming Vantongerloo and the Dutch Van Doesburg, both proponents of the Neoplastic group De Stijl. Abandoning the colour fields of his dot and ellipse paintings in the late 1960s, Poons began flinging paint across his canvases, controlling thick layers of pigment with expert dexterity. Gradually, his pictorial surfaces became increasingly emphatic as he loaded them with inert materials that create three-dimensional relief.

In the early 1960s, both Bannard and Poons were lauded as Minimalists; by the end of the decade, they were creating literal pictorial surfaces that were as textural as they were optical. In Poons’ case, the material relief of the surface became increasingly pronounced, to the point that shadows accumulated in crevices thus producing chiaroscuro. Their concerns with tactility and surface texture pointed to a direction that advanced painting would begin consciously to pursue. In the late 1960s, Greenberg’s insistence on absolute flatness was also challenged by geometric painters like Ron Davis and Al Held, who invented ways of using perspective, the basis of illusionism, in a self-contradictory manner that subverted any reading of space behind the picture plane. At the same time in France, the Supports/Surfaces group was deconstructing painting into its constituent elements by detaching the canvas from its supporting stretcher.

Beginning in the 1980s, Greenberg’s purist dogma was challenged on all fronts. European critics, such as Achille Bonito Oliva, first used the term “Postmodernism” to champion Italian Transavanguardia painters, who mixed historical styles in pastiche figuration. Frederic Jameson characterized Postmodernism as a breakdown of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture by appropriating the kitsch imagery of mass culture in quotations and reproductions. If, in the 1930s, Greenberg exposed the antithesis of kitsch and the avant-garde, a half century later, Postmodernism now made it possible to identify the two.

The first major defector from Greenbergian orthodoxy was Poons, who began spilling heavy coats of thickened pigment, layering surface upon surface, until a relief high enough to cast a shadow was built up. Serious painters were seeking alternatives to Greenberg’s disembodied abstraction addressed to eyesight alone. Realizing that this narrow doctrine collided with the desire to retain the wholeness of the aesthetic experience made available by the Old Masters, they focused on the haptic quality of sensuous painterly surfaces, as well as on the optical fusion of colour and light, by experimenting with new kinds of materials and a variety of techniques analogous to the physical processes that the Surrealists used to evoke surprising images. Paintbrushes were abandoned for rags, sponges, mops, and spray guns. Stencils were used to mask areas that once removed did not depict images but left contoured shapes whose edges were not drawn but emerged from the process.

Miró’s concept of automatism as a means to experiment with materials and techniques, allowing the image to emerge from the process, anticipates the frontiers of serious painting today. Like Miró, the painters in this exhibition do not preconceive and depict shapes, but rather allow them to emerge from the process of creation. Describing his method of organising chance improvisation with stable structure, often combining linear looping and flat contoured shapes, Miró remarked, “The works must be conceived with fire in the soul but executed with clinical coolness.” He permits spills and blots to evoke pulsating forms. Miró’s paintings may look casual, but the disposition of elements is like in those of the Old Masters. He causes the eye to travel across the surface along axes and paths that visually link form to form. Miró challenged and threatened the Cubists: “I shall break their guitar.” And indeed, with his fearless experimentation, one might say that Miró certainly did.

Given what we are seeing today, Miró may well have been right. His new method of working involved loose brushing, spilling, and blotting thinned-down, liquefied paint in conjunction with cursive, automatic drawing punctuated with shapes that were frequently vaguely geometric. The sense of an immeasurable cosmic space is common to the imagery of a number of the painters in this exhibition, both Americans and Belgians, such as Walter Darby Bannard, Joris Ghekiere, Bernard Gilbert, Karen Gunderson, Lois Lane, Paul Manes, Werner Mannaers, Marc Maet, Bart Vandevijvere, and Jan Vanriet.

The manner in which the artists in this exhibition actually work is often a mystery because of the number of different techniques that they employ to apply and remove paint. These are not what Greenberg referred to as “one shot” paintings, executed so quickly that they are finished the moment that the single coat of stained colour dries. On the contrary, each painting is worked on over a period of time, its composition assessing and reassessing the balance, seeking equilibrium through subsequent retouching. Each part has to function successfully within an integrated surface. This is the challenge that Cézanne gave himself, constantly reviewing and readjusting his paint patches and their closely valued colours until he achieved the desired equilibrium over a period of time.

Minimal reductiveness can now be seen for what it is: a transitional step in the history of art, one necessary in order for painting to gain new freedom in favour of the play of the imagination. This new kind of pictorial space is allusive and not literal. The picture plane is recognizably flat, but on it, or in it, float any number of individual visions of a space that is neither that of the academic illusionism of the past, nor that of painting as a strictly literal object. New interpretations of texture and space, with their connotations of both tactility and metaphor, obviously vary from artist to artist.

The artists in this exhibition work alone, slowly and painstakingly, revisiting their compositions many times. Their works are made in a slow process and require time to be digested by the viewer. They slow down rather than accelerate time. What they have in common is a syncretic attitude that conserves that which remains vital from the art of the past by analysing and distilling the essence of the pictorial.

Barbara Rose is is an art historian and curator who lives in New York and Madrid, Spain