For a decade, from 1973 to 1983, Charles Atlas was the film-maker-in-residence for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, collaborating with the choreographer and his dancers to create a new way of translating dance onto the screen. So when the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis was looking to commission new works for its major exhibition on Cunningham opening in February 2017, one of the artists it turned to was Atlas. The result will be Tesseract, perhaps one of the most technically ambitious dance recordings ever made, incorporating 3D film, live performance and on-the-spot video-mixing by Atlas, working in collaboration with two former Cunningham dancers, Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener.

The work is being finished this winter at the Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (Empac) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, upstate New York, which co-commissioned the piece. It will premiere at Empac in January, before being shown at the Walker, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and other venues across the country next year.

The Art Newspaper: How did this commission come about?

Charles Atlas: Empac invited me to do the residency. When I went up there, I wanted to do everything. All the things I ever wanted to do, they had [the tools] there. And then I realised I had to narrow it down. I’ve always wanted to do something in 3D. I tried doing live video with dance once and it wasn’t very satisfactory because we had no time to work on it. So I thought this was my chance. Then I had to choose collaborators. I wanted to work with someone I hadn’t worked with before, and someone who was sort of brainy also, so Rashaun and Silas were perfect. We decided that we would do the 3D film one year and then the next year we would work on the live part. I always wanted it to be [shown in] one evening all together, so it’s going to be the 3D film for the first act and then the second act will be the live dance with live cameras, live [video] mixing, and projection on the scrim in front of the dance.

You’ve done lots of live video-mixing pieces.

Not with dance. I’ve done it with live performance, with people speaking in place or moving more or less in place. That’s easy to do—well, not easy, but adding high-energy dance where people are moving radically through space is a whole different thing. We’re intensively working in November, December, to make the second part in New York and then part of the time at Empac. Because it’s hard to work on it without having all the equipment, you need someplace where you can set it up and leave it, because the setup is so complicated.

Tesseract is described as a six-chapter work.

That’s the 3D film. What Silas, Rashaun and I decided we have in common was we all like science fiction. So we decided we’d have a science fiction theme. A tesseract is a four-dimensional cube. The film is really six different 3D worlds that are very different-looking and have different approaches. The live part will have more of a through line.

How are you going to approach the live performance?

We’re heading into the unknown—really, we are. I mean I have an idea that maybe what you see on the screen is the quantum-world version, but I don’t know how that might pan out, because when you work with live video, you have a slight delay. I mean with dance, I can really tell the difference, especially on fast movements, that they’re not exactly in sync. We haven’t really decided how we’re going to approach that, but there’s going to be some pre-recorded movement, and then some live capture that’s played back later, and then some abstract stuff that will be on the screen. The challenge is to try to meld this, to have it be not competing with the dance but have it be a complement to the dance.

When you say you’re thinking of the quantum world, will dancers be in two places at once?

In the quantum world, the theory is that there are simultaneous realities of things that happen at the same time, but they happen in a different way. The time factor is not the same—everything is present. These are all far-out concepts that we’re not really going to illustrate, but it’s just part of my thinking.

You’ve said that you are interested in new technologies. Are you looking at virtual reality at all?

I’ve been editing for a year practically on this film. It’s very labour-intensive and time-intensive to do what I want to do. I don’t see how you do VR without a team. I’m basically doing this myself—I mean, I have an assistant, but creating a 360-degree world is so detailed, there’s so much information that needs to go in virtual reality… I haven’t really gone into that. I draw the line. I’d already drawn the line at one point saying I was never going to do 3D. Then I did. And I’m sorry that I did in a way because I’m learning how hard it is [laughs].

I’m enjoying it. It’s just hard work. There’s a lot of restrictions in filming in 3D that I didn’t realise at first. Most Hollywood 3D is shot with 2D cameras. I mean, talk about labour-intensive—teams and teams of people doing the post-production. It’s so expensive. Shooting in 3D is a different kind of hard, and I think they couldn’t do a lot of what they want to do visually if they had to use a stereoscopic setup.

How does that work?

You have two cameras mounted together, one on top of the other: one shooting down into a mirror and the other one shooting straight. There’s a lot of matching up you have to do and it’s very delicate. And it weighs 100 pounds, the rig. One of the shots in the film is a nine-minute-long steadicam single shot. I never got a perfect take because the person [carrying the camera] nearly died at the end of every take. [laughs] They were like: “Can you break it down to more shots?” I was like: “No, I can’t.”

The whole thing has been really challenging and interesting. As I said, the way it should be, but it makes me very nervous to have to come out with a piece at the end.

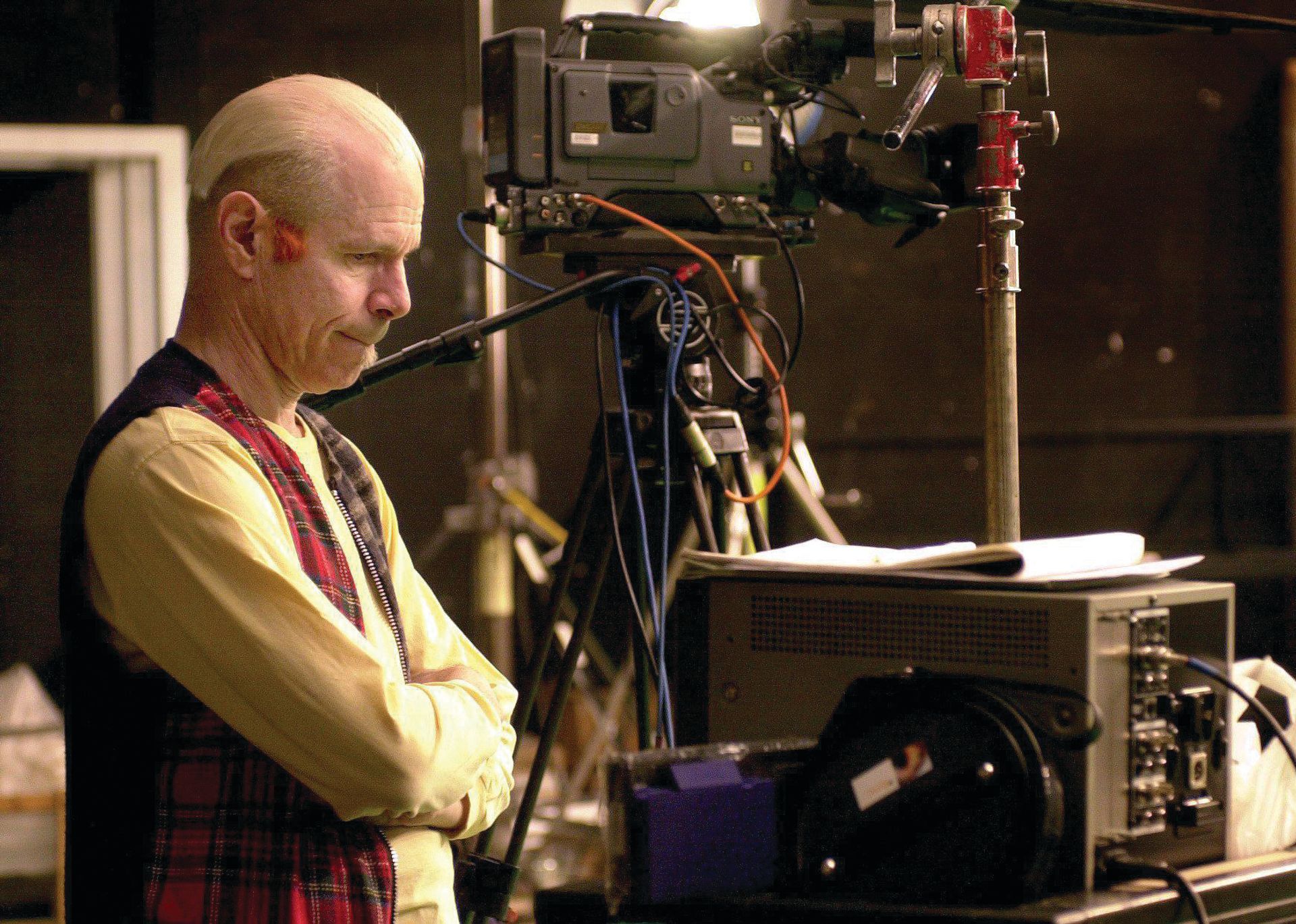

Biography: Charles Atlas Born in St Louis, Missouri, in 1949 to a housewife and a travelling salesman, he becomes interested in theatre production at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, but leaves before graduating to move to New York City.

In 1970, after volunteering as a stage manager at Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, the home of the avant-garde performance and dance scene, he takes a job at Merce Cunningham’s dance studio, where he designs sets, costumes and lighting, and serves as videographer-in-residence. He also collaborates with other choreographers, such as Douglas Dunn and Yvonne Rainer.

In the 1980s, he moves to London, where he works with performers such as Leigh Bowery and the choreographer Michael Clark (his documentary The Legend of Leigh Bowery came out in 2002).

Moving into the 1990s, he is commissioned to create experimental video series for television broadcasters such as PBS and the BBC, and continues to work on episodes of the programme ART21, for which he wins a Peabody Award in 2008. He delves into live video-mixing in the 2000s.

His work is in the collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Centre Pompidou. He is represented by Luhring Augustine in New York and by Vilma Gold in London.