Der Kunstkenner Max J. Friedländer: Biografische Skizzen (The Connoisseur Max J. Friedländer:

Biographical Sketches)

Simon Elson

Walther König, 527pp, €48 (hb);

in German only

The title of Simon Elson’s biography points to what Max Friedländer was and how he saw himself: “der Kunstkenner”, a type that has almost been forgotten in today’s art scene: the connoisseur with the unfailing eye. Friedländer’s connoisseurship was famous; Elson also endeavours to emphasise that he was a historian.

Elson’s biography is set in the context of Jewish emancipation in Prussia. His family were in the jewellery business (and later in banking), rising to become imperial court suppliers. Max Jakob Friedländer himself “embodies an important part of the emancipation story. Despite his Jewish origins he became not just a Prussian civil servant—unusual, even around 1900—but even a museum director”. Yet he did not see himself as Jewish and, when a group of high-profile Jewish art lovers planned to establish a private Jewish Museum in 1929, he expressed “reservations”: Elson describes it as the “sensitive reaction of a Prussian official of Jewish origin who did not want publicly to be linked with ‘Jewish politics’”.

Max Friedländer belonged to the Golden Age of Berlin’s Preußische Museen (Prussian museums). He was the director of the Kupferstichkabinett (department of prints and drawings) for 22 years, and the director or deputy director of the Gemäldegalerie (paintings collection) for almost the same length of time. Alongside his work as museum director, Friedländer achieved prominence for his art-historical writing, especially for his Early Netherlandish Painting (1903). Friedländer’s language is clear, and Elson explains: “Friedländer achieves his clarity by taking plain historical descriptions and adorning them with poetic stylistic reflections that conjure up an image even for readers who do not know all the paintings discussed in detail.” (2,000 illustrations were added to the English translation.)

Friedländer’s quiet existence in the civil service took a dramatic turn in the Nazi era; he had to emigrate, but went only as far as the Netherlands, shielded from arrest and deportation on the orders of the top Nazi and leading art looter Goering (“the Jew Friedländer is not to be harassed”). His connoisseurship was clearly still in demand: dealers acting on the Nazis’ behalf visited him regularly in Amsterdam. He was very fortunate to survive, although he never dwelt on the drama of his situation. After the war, he wrote laconically: “In danger for being the wrong race during the occupation, and the wrong nationality after it, I was preserved from misfortune by fortunate coincidences.” He remained in Amsterdam where he died in 1958.

Bernhard Schulz is the art critic of Der Tagesspiegel, Berlin

The Mystery of Marquis d’Oisy

Julian Litten

Paul Watkins Publishing, 192pp, £14.95 (pb)

Julian Litten has had a long and distinguished stint on the curatorial staff of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and has been described as a “funerary historian”, well known for an obsessive, if not morbid, interest in the cultus of death and the departed. This monograph is an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to lay to rest a personal ghost for Litten, which goes back to his discovery as a teenager of the glories of Thaxted church in Essex. In the byways of early 20th-century Anglo-Catholicism, Thaxted has its own particular niche, carved out by the contradictions in the personality of Conrad Noel, its vicar from 1910 to 1942, who combined radical socialist politics with the reinvention (his vision) of pre-Reformation England in the depths of rural Essex. Possibly a saint, certainly a dreamer, Noel drew around him a whole circle of gifted oddities, of which there was none odder nor more gifted than the subject of this book.

Litten directs shafts of light onto the history of the man who was known as the Marquis D’Oisy, but in the end has to admit that the mystery is impenetrable. Ambrose Thomas was his real name and, although born a Catholic in 1881 and dying as one in 1959, he seems to have flirted for most of his life with various forms of exotic Anglicanism, settling down to a career of acting—pageants were a speciality—and domestic and ecclesiastical decoration. (At various times he was employed by the cabinet-maker Maples and the church furnisher Louis Grosse.) The hints at aristocratic Brazilian and French antecedents would seem to have been sheer fantasy. While never short of patronage, he was rarely out of debt. It is the painted furniture that first attracted Litten’s notice and the examples reproduced here do certainly reveal a dated charm. In an uncharacteristically terse foreword, Sir Roy Strong offers the thought: “I can totally understand the author’s fascination with this elusive off-beat character… who could have walked out of one of E.F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia novels.” The personal reminiscences of those who knew Thomas are fascinating in that they conjure up images of a deferential society where people seemed happier with their lot. Is this short work no more than a generous “homage” to a peripheral figure of little interest to any but a few? Yes, but it has awakened in me, at least, the desire to revisit Thaxted and perhaps even to make a pilgrimage to the Marquis’s grave at Great Dunmow.

Christopher Colven is the rector of St James’s Catholic Church, Spanish Place, London

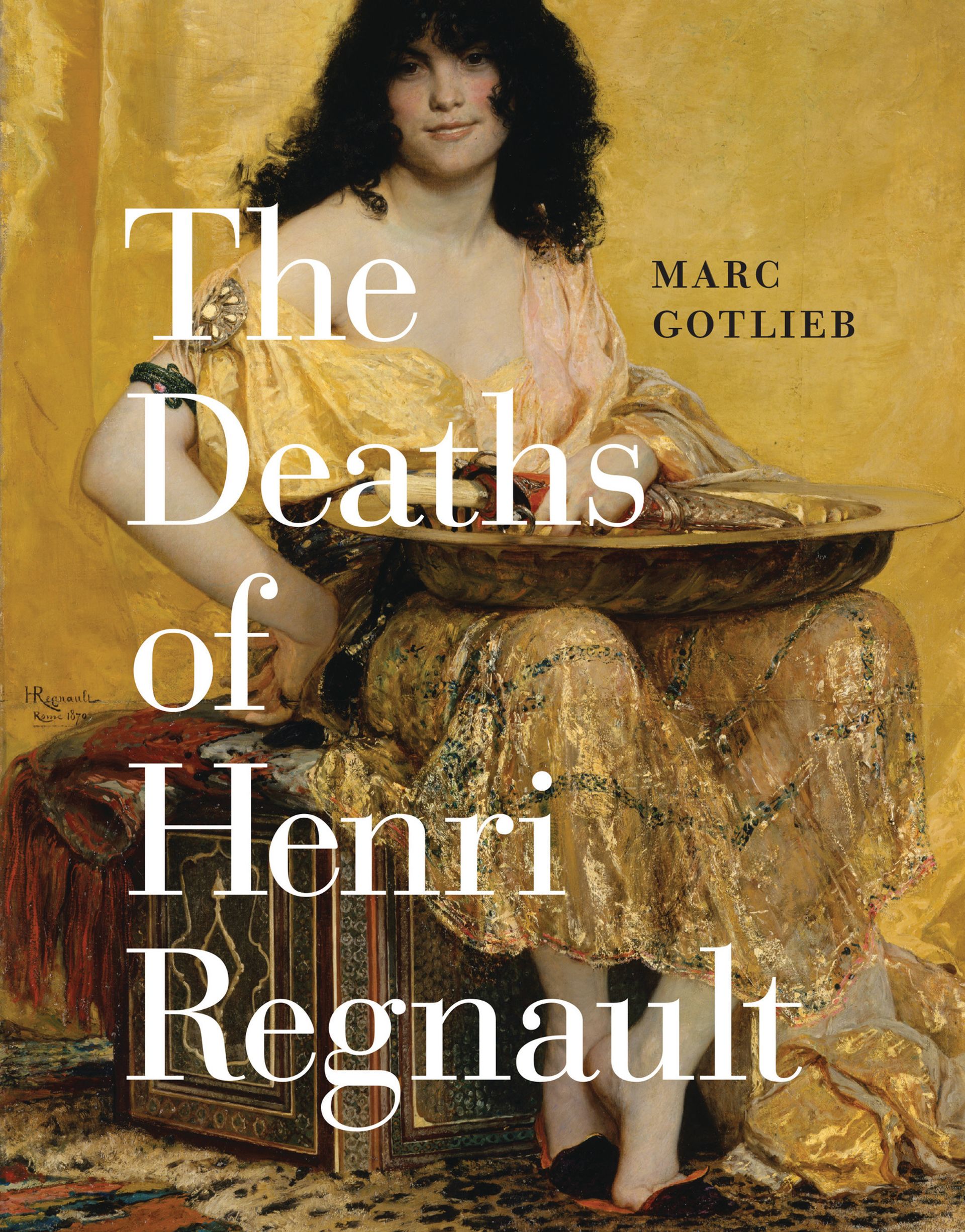

The Deaths of Henri Regnault

Marc Gotlieb

University of Chicago Press,

320pp, £42, $60 (hb)

The painter Henri Regnault (1843-71) has been perhaps best known for his premature death at age 27 in the Franco-Prussian War and for a Salomé which caused a sensation at the Salon of 1870 and later became a textbook example of the worst sort of Orientalism. Marc Gotlieb sets out to reassess both the painter and the mythology that grew up around him. The result is an absorbing book which not only affirms the interest of Regnault’s small but striking œuvre, but also examines his posthumous reputation, from its high point after his fall in battle, to its cataclysmic decline as Modernism took hold, and finally to near oblivion as the paintings themselves were relegated to the storerooms of the museums that had once fought so hard to obtain them. Gotlieb has a good eye, a keen attention to language, and a subtle understanding of the dynamics of cultural memory.

As the title implies, Regnault had many lives as well as deaths. Having won the Prix de Rome in 1866, he left for Italy but spent much of his tenure travelling, notably to Spain and North Africa. He produced large canvases—of rich, almost garish colourism, replete with overt or implicit violence—which combine an imaginative exoticism with a raw realism that takes the viewer by surprise. In chapters focusing loosely on his early paintings, Gotlieb ranges widely to explore Regnault’s pictorial sense of belatedness, his relation to tradition and the Moderns, and his experience of the “Oriental sublime” that gave rise to some stunning watercolours. Two subsequent chapters make a case for the powerful effect of Regnault’s Salomé (1870) and Execution without Judgment under the Kings of Morocco (1870), paintings which seem almost caricatural in their theatricality but which Gotlieb’s analysis manages to make interesting. The remaining three chapters explore Regnault’s legend and reputation, their enlistment in the service of a patriotic mythology after the 1871 defeat, his fortunes in the US and the total collapse of his reputation. These later chapters are somewhat leisurely and display some repetition, but overall this is a compelling book about a painter who inspired strong reactions on both sides of the debate, from Gautier’s gushing “symphonist of colour” to Zola’s sneering “Delacroix corrected by Gérôme”. Gotlieb himself acknowledges falling under Regnault’s “spell”, and, if he does not convince everyone of his subject’s powers of enchantment, he nevertheless makes him seem well worth the effort, and tells a good story in the process.

Michèle Hannoosh is a professor of French at the University of Michigan. She is the editor of the recent French edition of Delacroix’s Journal (2 vols, 2009) and of Eugène Delacroix: Nouvelles Lettres (2000), and the author of numerous works on 19th-century French art, literature and society. She is the editor of Word & Image

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation

James Stourton

HarperCollins, 496pp, £30 (hb)

At the end of this masterly, thoughtful and very moving biography, the author asks how his subject, Kenneth Clark—sometimes dubbed, after his widely-known TV series, “Lord Clark of Civilisation”—might wish to be remembered. His response is to invoke Flaubert’s dictum: “l’homme est rien, l’oeuvre c’est tout”. In his account, James Stourton, a former director of Sotheby’s UK and senior fellow of the University of London’s Institute of Historical Research, narrates the vast range and colossal scale of Clark’s accomplishments: the youngest-ever director of London’s National Gallery, leading specialist on Leonardo da Vinci, Renaissance art scholar, highly effective patron of—and committee leader for—the performing and fine arts, social lion, diverting memoirist and incomparable communicator of art, in the media of lectures, writing, film and television. This Stourton does equitably and in clear, direct prose, all the while astutely analysing each stage of Clark’s career. Inspiring him all his adult life, states the author, was Ruskin’s credo that “beauty was everyone’s birthright”.

Stourton begins his book with the calling, in March 1934, of King George V at the National Gallery, “the first time a reigning monarch had visited the gallery”. The king’s motive: that the 30-year-old director assume the added position of surveyor of the king’s pictures. Clark could not decline the offer. Formerly in charge of about 2,000 pictures (at the National Gallery), he was now responsible for some 7,000 more. With the coming war, all of these treasures had to be evacuated for safekeeping, a tale Stourton recounts in riveting detail.

This biography was commissioned by Jane Clark, the widow of Kenneth Clark’s eldest son, Alan, and the current châtelaine of Saltwood Castle. Yet there is nothing “official” about it. Indeed, its longest chapter, Saltwood: the Private Man, sometimes makes for painful reading: the idea of the Great Man had to be tempered with accounts of self-doubt, family squabbles and his girlfriends. (One diverting detail is, however, that Clark kept his Mars bars in his safe.) Archival information pertaining to Clark would appear to be limitless: from that maintained at Tate Britain (of which the catalogue alone, we learn, runs to 765 pages) to records at Saltwood and the Berenson correspondence partially preserved at Villa I Tatti, Florence. From all this (and much more), Stourton has written an exceptional and fascinating book.

Eliot W. Rowlands is a freelance art historian and specialist in early Renaissance Italian paintings. He served as the senior researcher for Wildenstein & Co for more than 25 years