An exhibition exploring the overlooked field of divinatory arts opened at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, last week (until 15 January 2017). For Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural, Francesca Leoni, the museum’s curator of Islamic art, has gathered more than 130 objects from private and public collections throughout the British Isles, around a third of which are on view for the first time. Dating from the 12th to the 21st centuries, the exhibits represent a wide swathe of Islam, from China, South East Asia, Nigeria and the Sudan to the great cultures of Egypt, Turkey, Iran and India. Local British Muslim communities have also been involved in the exhibition and accompanying programme.

One of the finest objects is an Iranian enamelled cup and saucer made for the Qajar ruler Fath ’Ali Shah, who reigned from 1797 to 1834. The cup is decorated with poetry, Western zodiac signs and personifications of planets and constellations. The latter are so finely detailed that facial moles and individual strands of hair are visible on the tiny enamelled faces. Holding the cup, the ruler metaphorically held the universe in his hand, while references in the poetry compare the holder to the sun, and his reflection in its golden interior to the moon. Beautiful and sophisticated, the cup is both literally and figuratively an object fit for a king.

The “supernatural” of the exhibition’s title is used to mean things beyond human control, primarily divine will. Divinatory practices are widely attested throughout the history of Islam, where astrology, geomancy and dream interpretation were considered sciences. Divination was used as a means of understanding the signs and symbols sent by God and of harnessing His power and protection. Orthodox opinion varied, but many historical texts focused not on whether the practices were legitimate, but on their proper, rigorous and scientific execution. Attempting to access the mystery of the divine in these ways was very much felt to be within the realm of Islam.

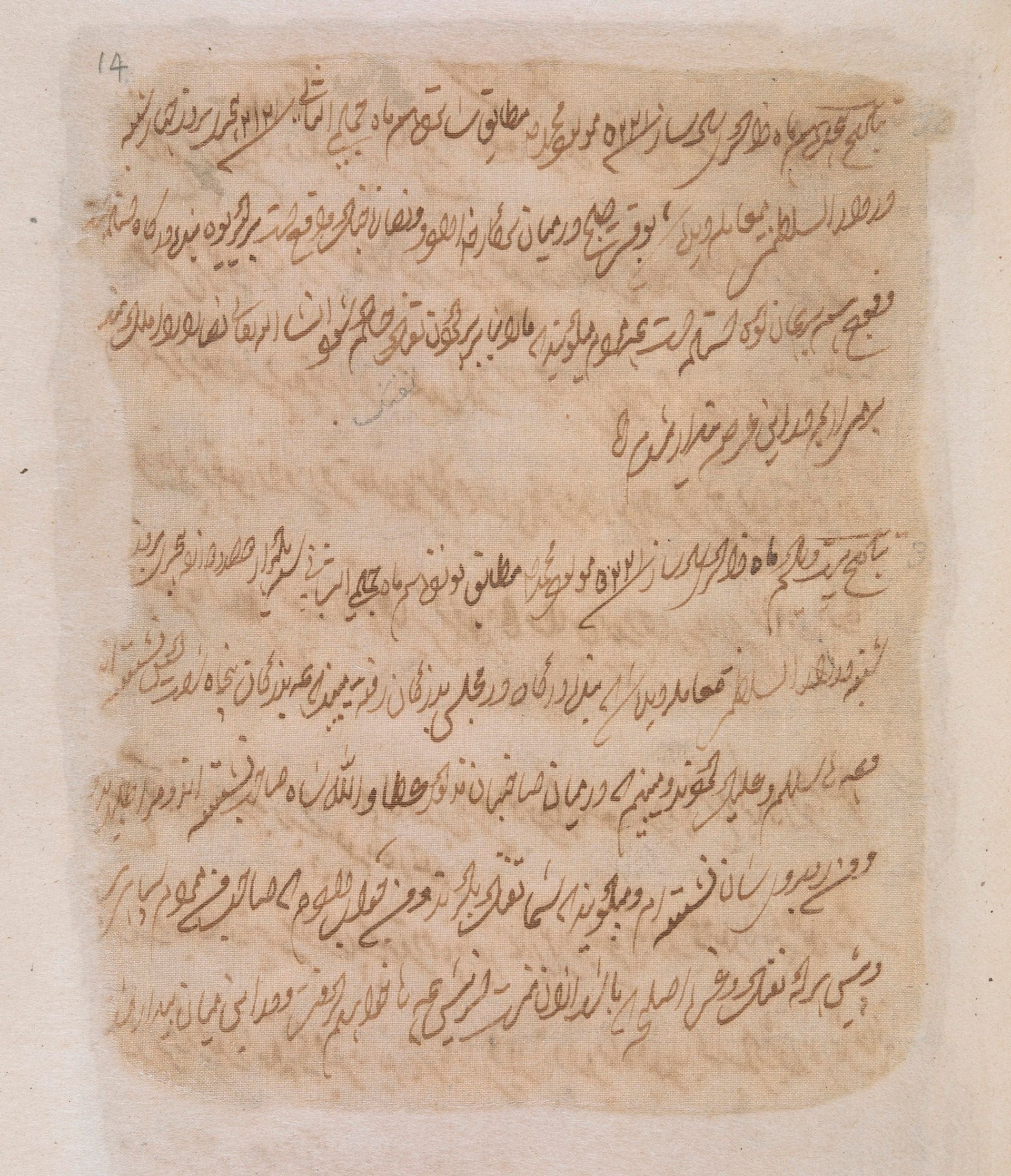

The Dream Book of Tipu Sultan from the British Library, which has never been exhibited before, reflects this. Hidden away, unknown to even Tipu’s most trusted vizier, the book was discovered after the sack of Seringapatam in 1799 and represents an intensely personal conversation with God. In it, Tipu interpreted his dreams as instructions from the divine, using them to inform his behaviour and adding notes afterwards to record the outcome.

The thoroughly researched catalogue superbly presents the richness of Islamic art in this field and greatly enriches understanding of the subject. Varying views on divination are carefully explored, reminding one of the diversity within any religion, and references are also made to similar practises in other faiths, such as the use of bibliomancy in both Judaism and Christianity. Similar balance and care is evident in the exhibition itself, affirming that the desire for closer access to divine power and protection is wide-spread across cultures and not peculiar to Islam.