In an admiring essay on his mentor, Roland Barthes, the art historian Yve-Alain Bois writes of how his teacher taught not through prescription, but through quietude. "Barthes insisted upon the silence of the master before his apprentices" for fear that his words would be taken as restrictive commandments. When he did speak, "the suggestions that Barthes made were nonviolent, since they so often lacked a precise formulation, but there was always a moral to what he said, an intimated morality." The tutor led by example:

"I was astounded, like everyone else, when I saw him take out a notebook from his pocket one day while I was speaking to him, and write down several lines before answering. Again a little later I observed the same action, but then realizing my mistake as I watched his scribbling hand, I knew there was no apparent connection between the fragments of language that were circulating in the air and what he was consigning to his notebook: that was the click, that turning of the key that released the association of ideas."

Barthes did not instil in his students a method (his own methods, anyway, were always evolving), but instead a respect for one's capacity for silent, inward reflection. He was an honest mentor; he knew the limits of all counsel. No great teacher, he understood, would ever try to simply transmit the moral of any given story from his mind to another. Such a task would always prove impossible. Only an individual reader could find the truth of a text, and only after he linked that text to his own lived experience. Barthes used to tell his students: "It's when you lift your head that you're really reading."

Here is another way of putting it, with a slightly different emphasis: "Art too is just a way of living." This was Rainer Maria Rilke's phrasing in a 1908 letter to Franz Xaver Kappus, the young poet who had written Rilke in search of guidance. Like Barthes, Rilke mentored largely through demonstration. Through seriousness of tone—seriousness that sometime devolved into melodrama—Rilke imbued the gravity with which the young poet should undertake his craft. "Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots onto the very depths of your heart," Rilke wrote to Kappus in 1903. Guidance would only take the young writer so far. The journey, in the end, was his alone to make: "No one can advise or help you—no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself."

How can such advice not betray itself? Kappus, Rilke must have known, had already looked within, and had found himself wanting. What the young poet needed was something from without to make his thoughts complete. Bois, too, in reflecting on Barthes, wrote of how he "didn't only want to quote" his master, but to "use his text in a sort of trusteeship," to seamlessly assimilate Barthes's ideas into his own. Kappus and Bois, like all disciples, sought from their teachers not just advice, but models to be emulated and absorbed. They wanted to know: how should one think? How should one live?

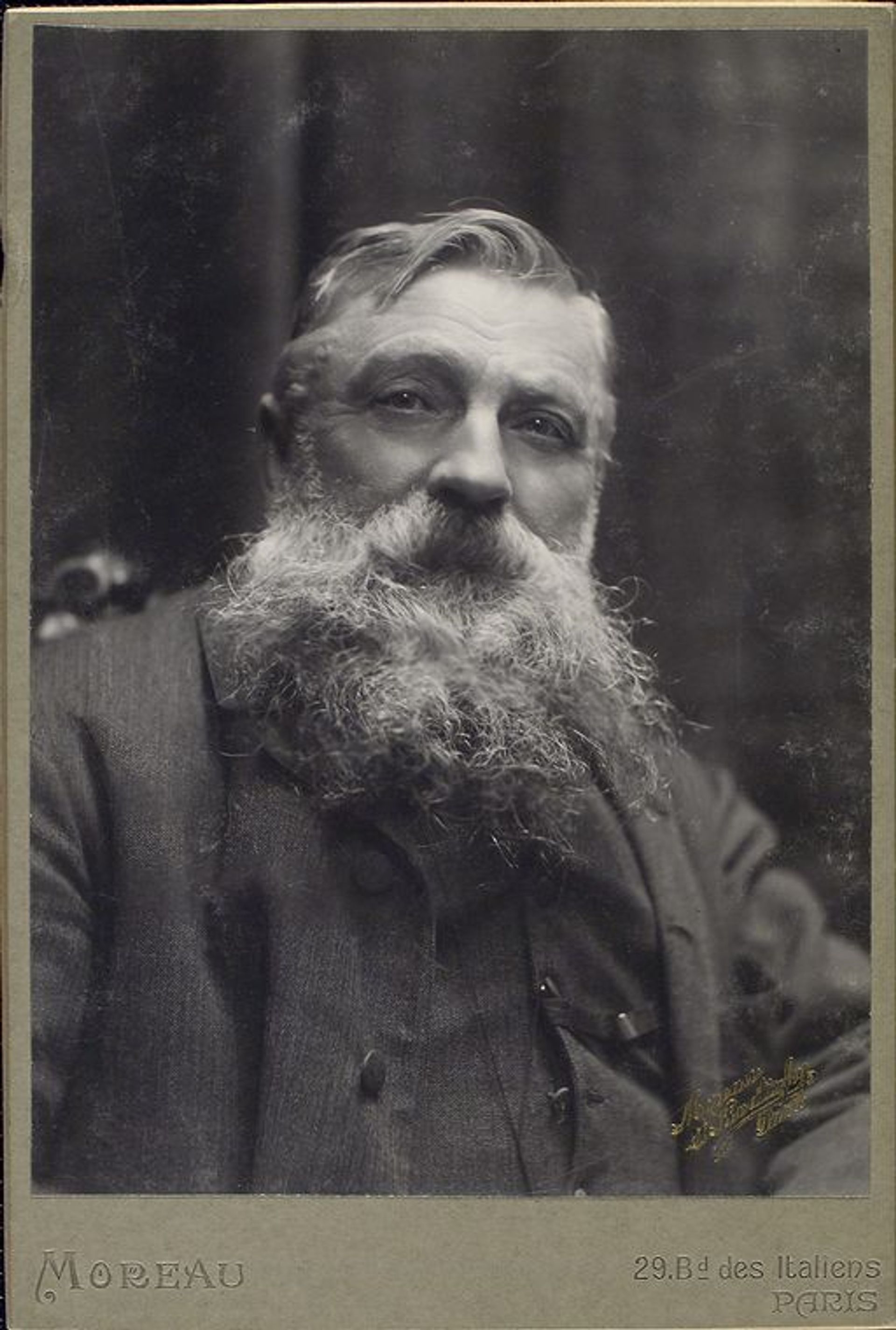

Such questions enliven serious writing, and they underpin Rachel Corbett's splendid new book, You Must Change Your Life. In the most basic sense, it is a chronicle of Rilke's intellectual apprenticeship to his own master, the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Deftly, and with great accessibility, Corbett describes their early lives and work; their first meeting on the artist's estate in 1902, as Rilke prepared to write a book on the sculptor; the poet's enchantment with Rodin, who implored the writer to leave the world behind and "work, always work"; their falling out, in 1906, over a trifling matter; and Rilke's ultimate realisation that his tutor did not have everything he was looking for.

At the bottom of it all is a moral position: that life and art teach us about one another. This is the foundation not only of Corbett's book, but also of the entire genre in which she is working; literary biography, indeed, assumes that an account of one's struggles and loves and desires and fears can illuminate something about his work. What follows is the delicate dance of sensitivity and empathy: how fully can a writer inhabit the mind of an artist? How deeply can she see through his life into his work? It is easy to assume a false equivalence between biography and criticism, as if one can be mapped perfectly on to the other. I think of Harold Rosenberg, who argued in 1958 that Abstract Expressionism had "broken down every distinction between art and life" and that, as a result, "anything is relevant to it." But who truly believes that "everything" is relevant to any one thing? To truly know that art and life are related is to ask about the nature of their proximity, not to assert it. The real problem is, if the two are intertwined, where does their mutual influence begin and end?

Corbett is admirably concerned with this problem in a way that Rodin never was. For him, art was art; life was something else, something to keep away. His studio and home outside Paris was a protective fortress against anything that interfered with his sculpture. At their first meeting, in Corbett's fine telling, Rilke despaired:

"The sculptor's house was depressing. There seemed to be no love in his family. Yet Rodin knew all of this and didn't care. He knew what he was, that he was an artist, and that was all that mattered to him. He abided by his own code, and no one else's standards could measure him. He contained within himself his own universe, which Rilke decided was more valuable than living in a world of others' making. In fact, it now seemed like a good thing that Rodin couldn't understand Rilke's [German] poetry, nor speak any other language. That ignorance secured him more soundly within his sacred realm."

Corbett continues: "As the poet breathed in the cool, damp air he felt a space open up inside him. It was a relief that came from realizing now the destination, even if he did not know yet how to get there. He had faith in Rodin and his assurance that hard work would guide him."

This is one of the many moments in which she writes not just about Rilke, but through him. Whole sections of the book are done in this free indirect style, wherein Corbett dips into Rilke's consciousness and imagines it aloud. She identifies with the poet more so than she does with the sculptor and there are moments, especially early on, where her attempts to dwell in Rodin's thoughts are less fruitful. Part of the problem is the false suspense that animates all biographies of successful figures. In describing Rodin's early schooling, Corbett writes of how he quailed at the "sculpt-by-numbers" style of teaching that characterised the academy: "Once he caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror and for a moment saw himself as his uncle, who had also been a plaster craftsman and wore a smock streaked with white paste. He was starting to believe that this job might be for him. Perhaps he had been foolish to think he could be an artist." Yet we all know how his story ends.

Still, even here, Corbett demonstrates that a biographer must, if she is to be successful, live through the thoughts of another. And just as she is immersed in Rilke, the poet was immersed in Rodin. In September 1905, the sculptor hired the poet as his secretary. Rilke's tasks were to handle all those pesky matters—business dealings, correspondence—that were beneath the artistic dignity of Rodin. He was paid 200 francs a month and given lodging in a three-room cottage. Here was a chance to bask in the glow of Rodin. "He wants me to live with him," Rilke wrote of his master to a friend, "and I could not do otherwise than accept; so I shall be allowed to share all his days, and my nights will be surrounded by the same things as his."

Such absorption is an attempt at empathy, which is appropriately the chief subplot of Corbett's book. Behind Rilke's apprenticeship to Rodin stirs a discussion between a group of thinkers—the art historian Wilhelm Worringer, the philosopher Walter Lipps, the sociologist Georg Simmel—who argued over the contours of empathy as a modern sensibility. Worringer in particular was concerned with its relationship to art. In his book Abstraction and Empathy, which was published in 1908, he claimed that abstraction was an albatross of upheaval and uncertainty, a signal of "great inner unrest inspired in man by the phenomena of the outside world."

Perhaps Rilke would have been receptive to such an idea; Rodin would not have been. He did not feel indebted to the world or its problems; they had little influence on his craft. When he implored Rilke to "work, always work," he also meant to steer the poet away from all supposedly extraneous matters. Yet Rilke's immersion in Rodin's life allowed him a window into the sculptor's contradictions. As Corbett notes: "By 1905, Rodin's studio in Paris was starting to look more like a brothel than a workshop." Nude models laid about or pranced around his atelier, drawn to Rodin "as a Pygmalion figure whose great hands could mold and reshape them." This was embarrassing to Rilke. "Once the Apollonian intellectual, impervious to temptation, Rodin had degenerated into the Dionysian hedonist, ruled by the body."

Yet Rilke tolerated it, until he was no longer offered the opportunity to do so. In April 1906, less than a year after he began working for Rodin, he was fired for liaising with a client that Rodin felt he should have been in touch with personally. "For Rilke," Corbett writes, "exile from Rodin was more than merely hurtful. It also cut short the crucial progress he was making as an artist. He felt like a grapevine pruned at the wrong time, and 'what should have been a mouth has become a wound.'"

By then, although Rilke did not know it yet, he had absorbed all he needed from Rodin, and the two shifted back onto separate tracks. The poet remained enthralled of his master and they stayed in touch intermittently, but the apprenticeship was over. Rilke travelled and read and wrote. He took his time and considered what he may have learned, and the lesson came slowly. "His mistake," Corbett shrewdly writes towards the end of her book, "was failing to grasp that Rodin could never tell Rilke how to live. The best any master could do was encourage their pupil and hope they find satisfaction in the work itself. In art, Rilke had started to realize, there was never anything waiting on the other side: There was no god, no secret revealed, and in most cases no reward. There was only the doing."

The truest sign of one writer's empathy for another is a respect for the inwardness of process, which always resists biographical light. Yes, a writer's stated ambitions and relationships and letters to friends and lovers can be revelatory. But these alone cannot ever fully uncover the obscure process of creation. Where does inspiration come from? Corbett looks into life as deeply as is possible for answers, but she knows when to stop. This is the hallmark of her moral intelligence. There is always a point at which the connections between art and life are only apparent; at this place, the relationship between the two fizzles away. Corbett knows this. Rilke knew it too, but it took him years to draw this lesson from Rodin. He tried to see what life should be by looking at Rodin's world, but that world remained, in the end, fugitive to Rilke. Later, the poet came to understand that even his own thoughts would remain somewhat elusive. In 1903, he advised the young poet Kappus to look within, but what did Rilke find when he took his own advice? "I'm learning to see," he wrote in his 1910 semi-autobiographical novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. "I don't know what it's about, but everything is registering in me at a deeper level and doesn't stop where it used to. There's a place within me that I wasn't aware of. What's going on there I don't know."

You Must Change Your Life

Rachel Corbett

W. W. Norton, 310pp, $26.95