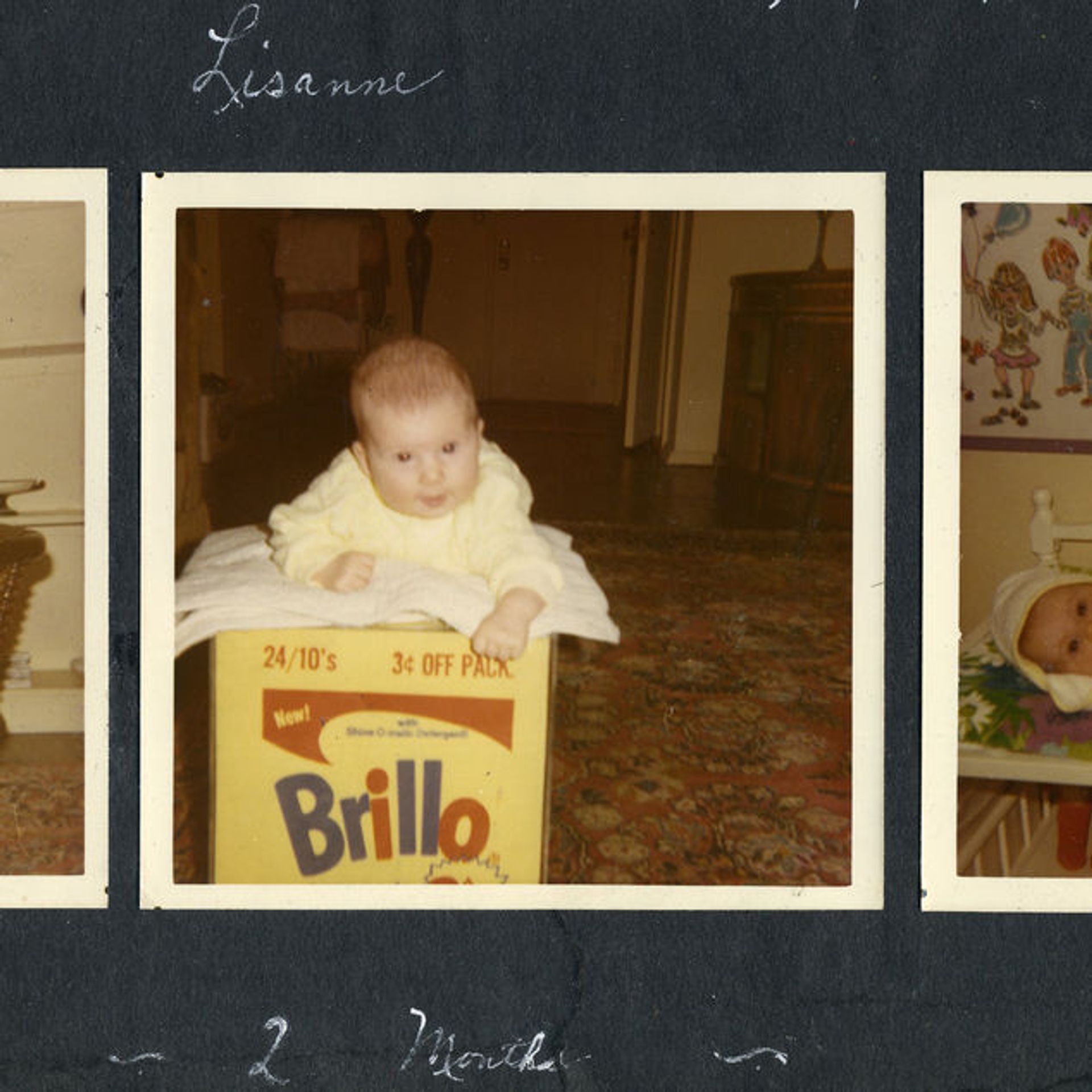

An art world novelty item that turned out to be a shrewd investment is the subject of a charming and clever documentary film. Brillo Box (3 ¢ off), which premiered at the New York Film Festival (until 16 October) and is due to air on HBO in early 2017, tracks the trajectory of a pop art piece by Andy Warhol that was originally bought by the New York filmmaker Lisanne Skyler’s family for $1,000 in 1969. It passed to owners in London and Los Angeles, until it ended up at an auction in New York in 2010, where it made more than $3m.

The original design for the soap scouring pad packaging was by James Harvey, an Abstract Expressionist painter who had a day job as a product designer. Appropriated in 1964 by Warhol, who emblazoned it with the discount label, the yellow box—a departure from the standard white—was sold in 1969 by Warhol’s dealer, Ivan Karp of OK Harris Gallery, to Martin and Rita Skyler, the filmmaker’s parents.

“I used Brillo,” Rita Skyler says in the film, describing how the Brillo Box defined a zeitgeist for her. Martin Skyler, then a young lawyer, had Warhol sign it. The rare Warhol signature boosted its value—yet Skyler traded the box two years later for a drawing by the psychedelically inspired Peter Young.

Charles Saatchi bought the box at Christie’s New York in 1988 for $35,000. After another sale at Christie’s during the art market slump of the early 1990s, Robert Shapazian of the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles acquired it in 1995 for $43,700. He exhibited it with other Warhol boxes in his living room until his death in 2010. A note that Shapazian left behind said: “art—the Warhol—had the power to help confirm to me that the past was over.” His estate sold it at Christie’s in November 2010 for more than $3m. The film does not name the buyer at that sale, but the work was auctioned again at Christie’s in May 2014 for $1.7m.

On one level, Brillo Box can be seen as the classic tale of the work of art that got away—from the Skylers at least. The couple talk of taking a chance in buying the box, covering it in Plexiglas, and using it as a coffee table. “I don’t think I would put a drink on it, but it was in the living room, and it could be Windexed,” Rita Skyler says.

“It wasn’t a piece that you fell in love with. When you get right down to it, it really wasn’t all that attractive… It was just a yellow box with some red lettering on it, basically,” Martin Skyler says. Explaining his decision to trade a now-valuable object for a work by the ever-obscure Peter Young, he adds, matter-of-factly: “I got something that hung on the wall rather than something that sat on the floor.”

If these sound like deadpan reflections, they are outdone in the film by Warhol himself, who is seen in archival footage. When asked to define Pop Art, he shrugs: “Why don’t you ask Ivan [Karp]?”

When an interviewer asks Warhol why he makes Brillo Boxes instead of something original, he responds: “Because it’s easier.”

The film also confronts the Warholian view of the art market. “He got what we were about. It’s about selling, it’s about making something appealing to be bought,” says Daniel Wolf, the director of a 2006 Warhol documentary, in an interview. “We buy, we shop, we own, we have.”

Lisanne Skyler quotes her mother’s more common sense market wisdom: “Just because something seems to have lost its value now, doesn’t mean you won’t wish you had it later.”

That observation might apply not just to Warhol, but to Peter Young, who told Martin Skyler when the two first met, “Why are you buying art? You should be buying real estate.”

Young reappears in Brillo Box when he has his first New York show in decades at Algus Greenspon Gallery in 2012. “I’m 75 years old, and I’m going to drop one of these seasons,” says Young, who relocated to Arizona to escape the fickleness of the market. “Then my paintings will quadruple in value.”