We are in the midst of a golden age of biotechnology. Cloning, human augmentation, DNA editing, genetic manipulation and xenotransplantation (inter-species grafting of organs or tissues) used to be the stuff of science fiction or gothic novels—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein comes to mind—but have now become fact. As biological scientists reshape the way we view ourselves and the world around us, artists are responding by engaging with living materials to express the opportunities and fears that come with an age marked by rapid change.

The French artist Philippe Parreno has dipped a toe into the world of bioscience in his Hyundai Commission for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, which opened this week (until 2 April 2017). He has created a bioreactor teeming with bacteria that serves as a living command centre for his multilayered installation.

But many artists have long specialised in “bio art”. They include pioneers such as Suzanne Anker, Kathy High and Eduardo Kac—best known for his 2000 transgenic work GFP Bunny, a fluorescent green rabbit. The next generation of bio artists includes Jaden Hastings, Helen Pynor and Špela Petrič, to name just three.

Although the term is hotly debated, bio art is generally defined as the use of live tissues, organisms and life processes in works of art. In William Myers’s book Bio Art: Altered Realities (2015), Anker writes: “Simply put, Bio Art employs the tools and techniques of science to make [works of art].” The artist, who is the chair of the fine art department in New York’s School of Visual Arts, which has its own bio art lab, adds that it is an art form that requires “dedication to two mistresses: the visual arts and biological science”. Some purists argue that bio art can come only from a “wet” laboratory where biological matter is handled, while others say non-lab works that are the result of rigorous scientific engagement can also be classified as bio art.

Heather Barnett, an artist and lecturer in the art and science master’s course at Central St Martins, London, works with bacteria, slime mould and cuttlefish. She sees the rise of bio art as part of a wider culture of diverse disciplines talking and responding to each other, with the tremendous growth of developments in the biotech field making it particularly pertinent at the moment. Bio art, she says, “reflects the aspirations and anxieties of our age”.

The potential for using cell growth to recapture eternal youth is explored in Heirloom (2016), a piece by Gina Czarnecki and John Hunt in which 3D portraits of Czarnecki’s daughters were created from the children’s own cells. The work will be shown in No Such Thing As Gravity, an exhibition opening at Fact (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), in Liverpool, on 11 November (until 5 February 2017).

Anna Dumitriu, an artist who works with bacteria and tuberculosis, says: “It’s the tension between beauty, horror and disgust that I find fascinating in working with microbiology. It’s the bacterial sublime—the vast quantities of these invisible microscopic things around us that have the potential to change us or even kill us.”

Who will buy it?

The market for bio art remains cool, at least for the moment. “The art market is always conservative,” Barnett says. “It doesn’t set trends. It’s trying to establish a market value.” Unlike traditional art forms, which sit easily on a wall or floor, bio art can be difficult to sell for logistical reasons. For example, an installation containing living systems requires specialist knowledge to install and maintain.

Also, the collaborative nature of bio art dilutes the impact of the culture of identity that the art market covets, Barnett says. “It loves the biography of the artist because it is selling the artist as well as the work of art. It took the commercial side of the art world a while to find a way to monetise installation, performance and digital art, and so I suspect it will be the same for bio art.”

Robert Devcic, the founder and curator of the art and science collaboration hub GV Art London, has spent over a decade working to place bio art works in institutions. “We’re trying to find a way to monetise to sustain these artistic practices, and it is proving very difficult,” he says. “I find it really hard to sell the actual bio art material.”

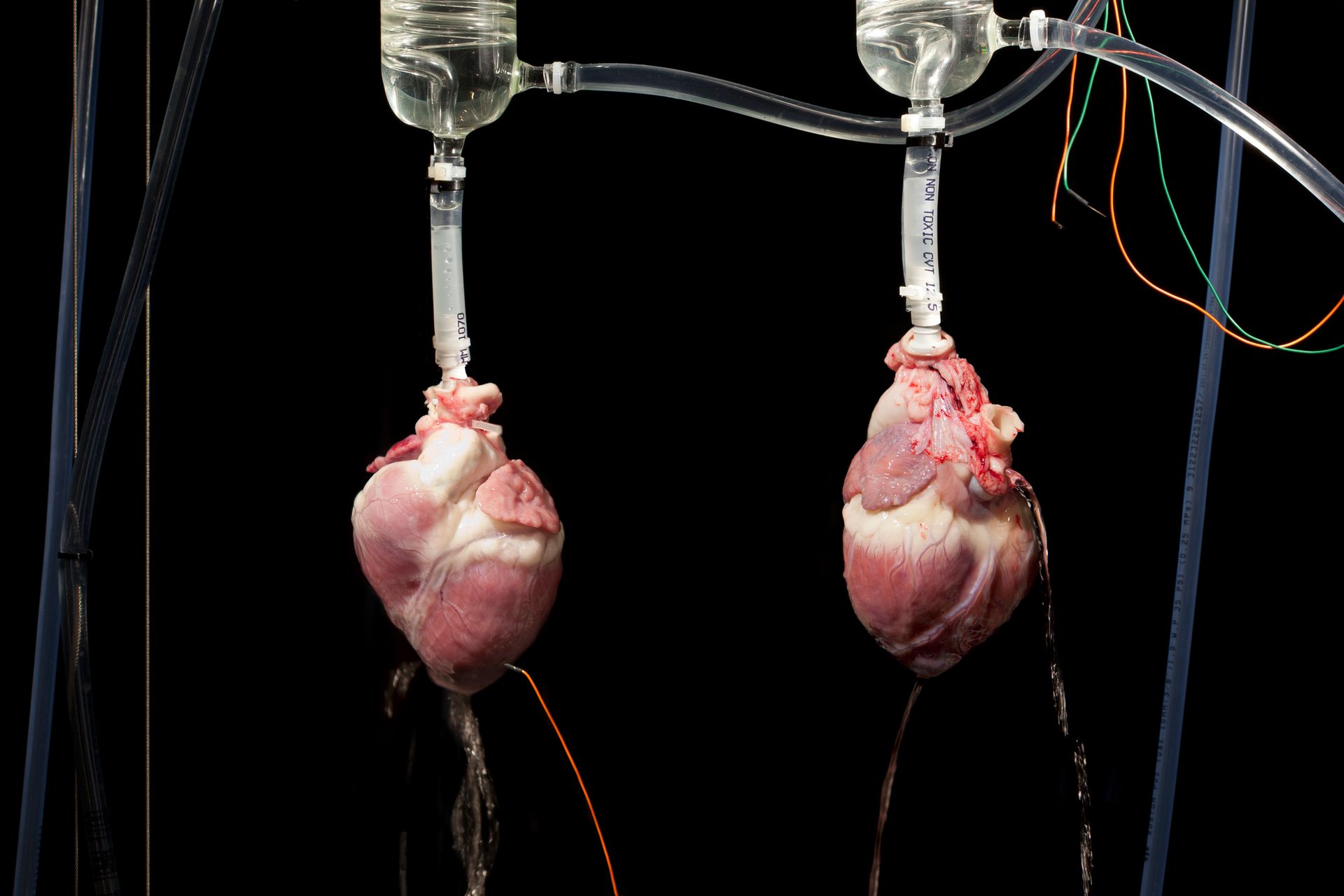

Devcic was unable to find a buyer for objects associated with Pig Wings, an ongoing project that takes the saying “if pigs could fly” to an entirely different level. The initiative, which explored constructing and growing wings using living pig tissue, was conceived by the Tissue Culture & Art project (TC&A) established by the artists Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr. The pair also founded SymbioticA—an arts laboratory based at the University of Western Australia in Perth.

As with installation and performance art, the artefacts and documentary materials associated with bio art projects may be the answer to cracking the market. GV Art London is selling limited edition photographic prints of coloured pig wings, made by TC&A in 2011, for £5,000. It also hopes to find an institutional buyer for plasticised garments from Victimless Leather—another TC&A project in which mouse stem cells were used to create a tiny semi-living jacket. The work was shown in 2008 in the Design and the Elastic Mind exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Bio art may be niche, but it is not a fringe activity, says Gemma Angel, a junior research fellow at University College London, who organised a recent conference at UCL on human biomatter in art. “It may not be mainstream, but it is at the avant-garde of contemporary art practice,” she says.

Bodies of work

Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr

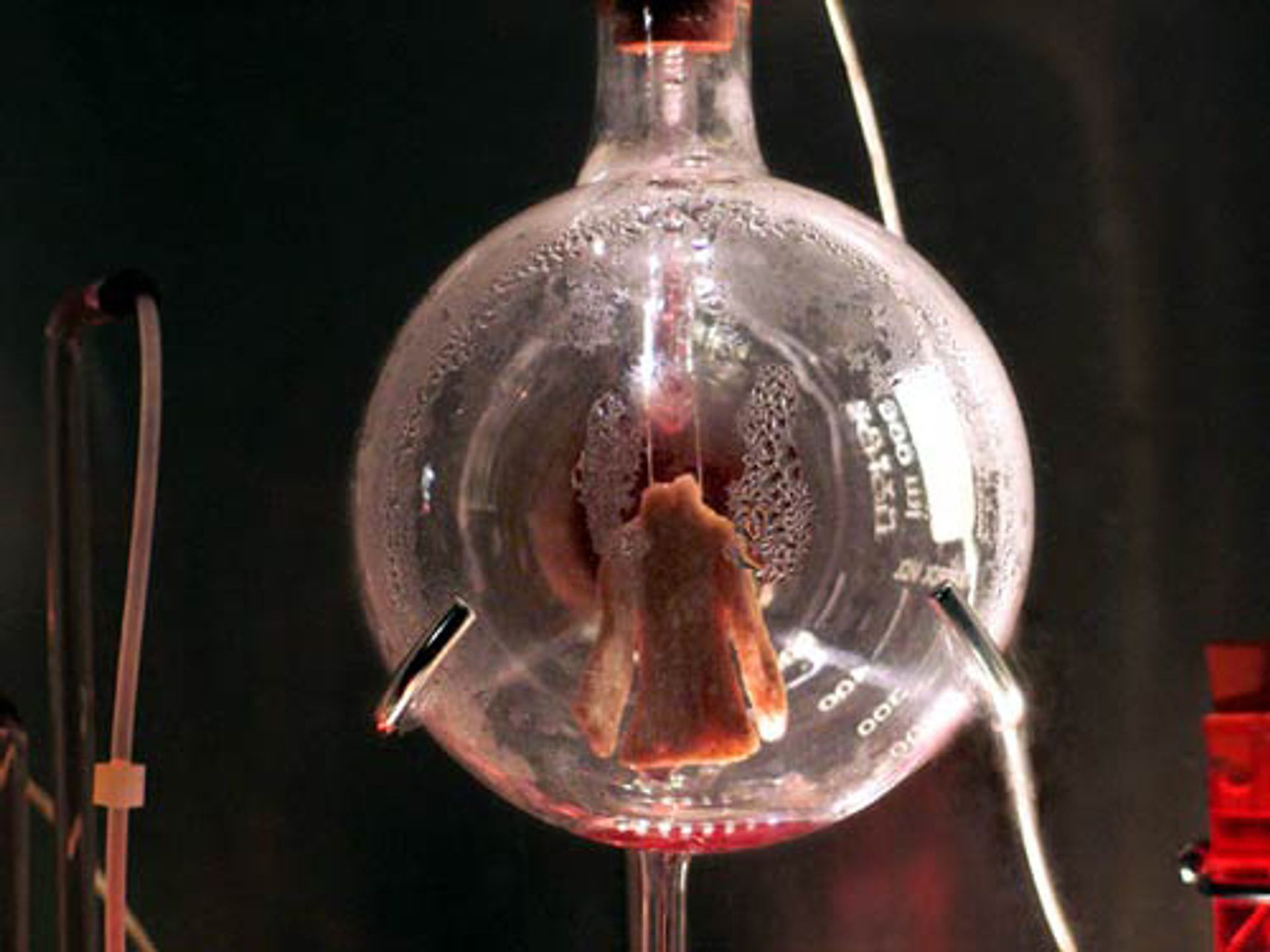

Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr are behind the Tissue Culture & Art project (TC&A), an initiative that explores the use of tissue technologies in artistic practice, hosted by SymbioticA—a cutting-edge arts and research laboratory at the University of Western Australia. Victimless Leather is a TC&A project that explores the moral implications of exploiting living beings. It ironically offers an alternative to wearing animal skin in the form of a tiny, semi-living jacket grown from mice stem cells. It was exhibited in 2008 at the Design and the Elastic Mind exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Marta de Menezes

The Portuguese artist Marta de Menezes’s Inner Cloud (2003) consists of her own DNA suspended in an ethanol-filled tube to create a cloud-like appearance. The piece was influenced by José Saramago’s 1982 novel Baltasar and Blimunda, in which the souls of those killed by the plague are said to resemble a cloud.

Anna Dumitriu

Pneumothorax Machine is from the British artist Anna Dumitriu’s ongoing project The Romantic Disease: An Artistic Investigation of Tuberculosis. Dumitriu is fascinated by TB and its related myths. She admits to being “obsessed with hunting down medical antiques related to TB” and found two pneumothorax machines in car boot sales in Brighton. These were used to collapse (or “rest”) the lungs of TB patients. In her piece, she carved the texture of lung tissue onto the machine’s case and engraved a positive TB sputum smear test onto one of its metal components.