Is it too soon to consign the 1990s to history? It is a question that many dealers coming to Frieze London might ask. It was the era in which numerous galleries that dominate the art world today—from Sadie Coles in London to Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York and Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin—came to prominence. As Gregor Muir, the outgoing director of the ICA in London and a prominent writer and curator in the 1990s London scene, says: “People are shocked that the 1990s is entering art history because it’s associated with a vibrant period in living memory.” Yet Muir agrees the decade is ripe for reappraisal.

Museums started the trend. The New Museum in New York and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, both recently staged 1990s-themed exhibitions. Frieze too has now dedicated a section to the decade, in which the Geneva-based curator Nicolas Trembley will revisit groundbreaking Nineties exhibitions. “Amid huge social and political change—the Aids crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall and rise of the internet—artists, gallerists, curators and critics felt like we were creating something new,” Trembley says. He adds that it is “the right time to revisit” the decade—“perhaps because we are experiencing another period of rapid change”.

Inevitably, the 1990s London scene is represented at the fair. There are works by the artist Michael Landy at the Thomas Dane and Karsten Schubert galleries, and pieces by the photographer and artist Richard Billingham at Anthony Reynolds. Work by the French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster on the Berlin dealer Esther Schipper’s stand reflect the European development of what became known as relational aesthetics—a concept coined and defined by the theorist Nicolas Bourriaud as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context”. Meanwhile, the German dealer Daniel Buchholz is re-creating photographer Wolfgang Tillmans’s first exhibition at his gallery in Cologne. And developments in the US are reflected in Karen Kilimnik’s work at 303 Gallery, among others.

Muir feels that the link between these diverse emergent scenes has been somewhat lost to history. Eighties New York art was, he says, “a key driver of what happened in the 1990s internationally, including in London… The likes of Jeff Koons, Ashley Bickerton—those artists showed in the Saatchi Gallery, and transmitted to younger generations of British artists that they could take matters into their own hands.”

Nineties art was profoundly influenced by Post-Modernism, Muir says, “which in New York saw the emergence of loft living—that sense of making do and getting by, dealing with the relics of an industrial past. YBA [the Young British Artists grouping] is a form of transatlantic ad-hocism.”

Cologne’s influence was also significant, Muir suggests—particularly the city’s fringe art fair, called Unfair, which began in 1992. The German city was “where British art established itself” on the European stage, he says, in “a real period of international exchange”. Schipper, then in partnership with another German gallerist, Michael Krome in Cologne, agrees. “It was the beginning for our generation of a whole new network, internationally,” she says. “It was also the beginning of globalisation and being aware of people finding the same interests in the same artists all over the world.”

For Trembley, “the power balance shifted from institutions to galleries” in the 1990s. “Because a new generation of galleries emerged [showing work by] artists that were not considered by institutions, commercial spaces, and the relationships between artist and dealer were so important.”

Hence Schipper and Krome’s decision to show Gonzalez-Foerster’s mock film set—an homage to the German film-maker Rainer Werner Fassbinder—in a Cologne apartment. The project, part of which is being restaged at Frieze, was more akin to those shown in non-profit spaces than in commercial galleries.

“We were in the deepest crisis in the art market,” Schipper recalls. “There were certainly things that were selling, but a lot of the work, even the very, very successful and highly speculated work from the 1980s, was difficult in the market. So we had to improvise a lot and, weirdly enough, there was more space for this [experimental] kind of work in the crisis than there was ten years later in the early 2000s, when the market was booming.”

Perhaps because of the closeness between dealers and artists, and because figures such as Damien Hirst so vividly embraced the art boom of the 2000s, 1990s British art increasingly has been caricatured as market-driven. That thesis will be tested in Christie’s Absobloodylutely, a multi-pronged online sale of contemporary British art from the Cranford Collection (4-13 October) established in 1999 with the support of Andrew Renton, the director of the Marlborough Contemporary gallery. The sale features key artists such as Rachel Whiteread alongside less widely celebrated figures such as Paul Winstanley.

But is 1990s art ageing well with young artists? Trembley thinks so: “The artists of the 1990s were experiencing a period of huge freedom. The art market was different, so the art world was less about selling and objectifying, and more about dematerialisation and socialisation. This was the start of the digital age—artists were moving away from traditional categories of painter, sculptor.”

Trembley cites the prominence of video art, the Swiss artist Daniel Pflumm’s experiments with music and online works, and the artists Pierre Huyghe, Jorge Pardo, Philippe Parreno and Matthew Barney’s engagement with literature, design and performance. “We can see these legacies in the latest generation of artists, for whom it is natural to work across disciplines and engage with audiences beyond the gallery context,” he says. “The 1990s generation made this expansion of artistic practice possible.”

Three who were key in the 1990s

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster

A frequent collaborator with other leading artists in the 1990s, Gonzalez-Foerster is associated with the theorist Nicolas Bourriaud’s notion of relational aesthetics. Fuelled by literature and film, the French artist’s work often fuses reality and fiction in poetic mises-en-scène, as in her creation of a bedroom once imagined by the film-maker Rainer Werner Fassbinder on show at Frieze this year.

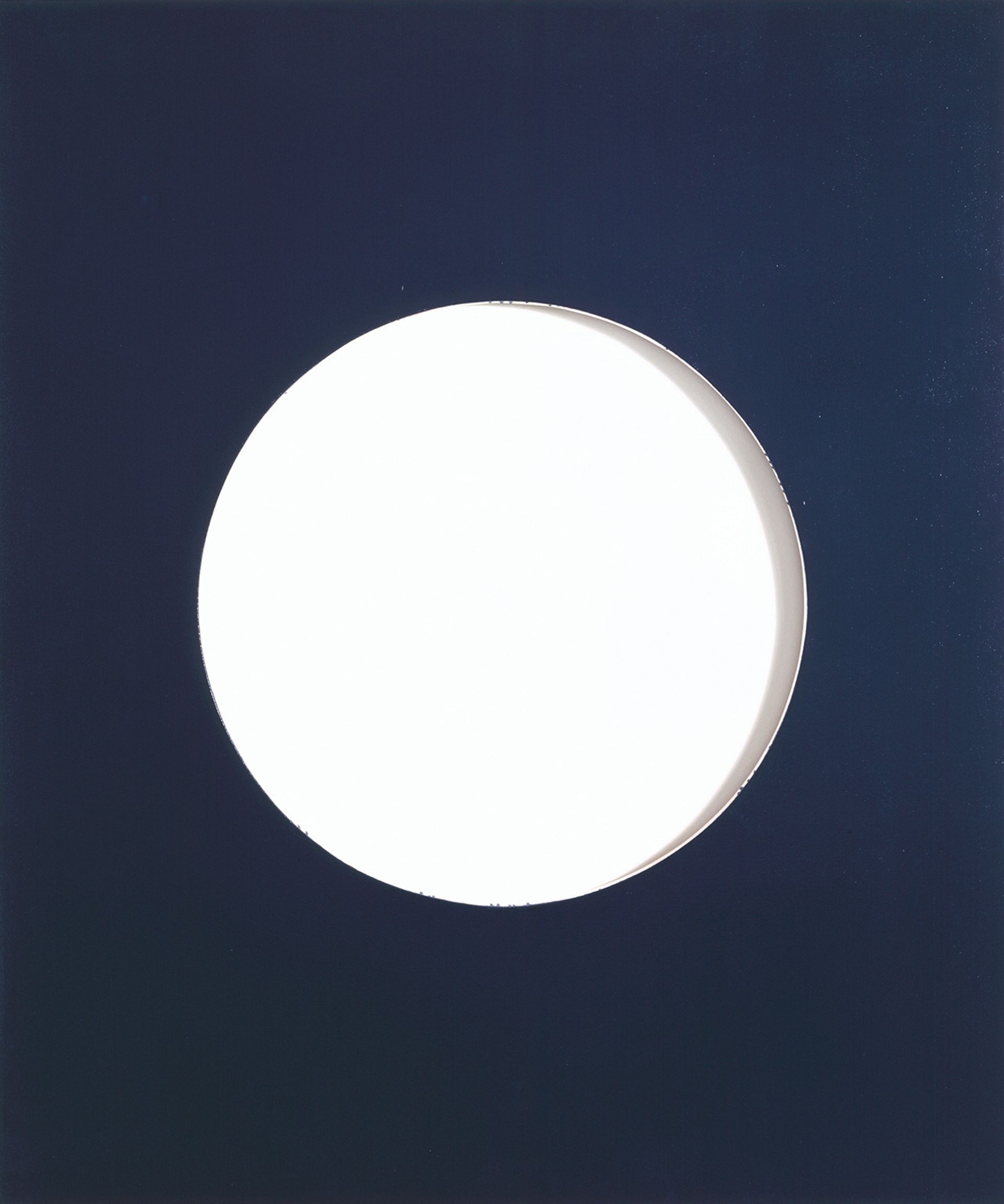

Wolfgang Tillmans

Tillmans’s work was discovered by his dealer Daniel Buchholz in the pages of fashion-culture publication i-D magazine. From his first exhibition at Buchholz’s gallery in 1993 (re-created at this year’s Frieze), Tillmans revealed his idiosyncratic approach to photography. The prints were made on different scales, from miniature to vast, and were stuck to the wall informally with tape. They were shown alongside magazine pages in an overall installation that reflected Tillmans’s eclectic use of the medium, from documentary realism to abstract formal experiments.

Steven Parrino

Though he had been on the art scene for some time and associated with neo-geo in the 1980s, Parrino’s career took a leap in the 1990s, particularly as his “misshaped” paintings drew many admirers. These monochrome canvases were torn, cut or crumpled, and often black, in keeping with Parrino’s interest in the occult and his passion for pop cultural phenomena such as punk and no wave music. At Frieze, the Swiss dealer Andrea Caratsch is showing a number of paintings by the late artist, which were originally exhibited at landmark New York spaces in the 1990s, such as the maverick dealer Colin de Land’s American Fine Arts gallery.