Ernst van de Wetering has written a fascinating and, appropriately given its title, a thought- provoking book. In 1997, he published Rembrandt at Work, informed by his profound knowledge of the artist’s working practice, based particularly on his research undertaken as a member, and then chairman, of the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP). In volume six of the RRP’s Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings (2015), he presented his definitive catalogue of the paintings. In Rembrandt: the Painter Thinking he sets out to discover the thought processes behind Rembrandt’s work. Can he be said to have had a theory of art? Or did he, as his Amsterdam contemporary Joachim von Sandrart said, “bind [himself] solely to nature and follow no other rules”? And are these—a theory of art and the unwillingness to follow rules—necessarily mutually exclusive?

In order to explore these questions, Van de Wetering analyses in considerable detail two key art treatises published in the North Netherlands in the 17th century. The first is Carel van Mander’s Het Schilderboeck (the book of painting), published in 1604, in particular the section that deals with instructions to young painters, the Grondt der edel vrij Schilderkonst (the foundation of the noble free art of painting), and the second, Samuel van Hoogstraten’s Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst (introduction to the high school of the art of painting), published in 1678. This analysis occupies the largest part of the book and takes the section headings used by Van Mander—for example, the proportions of the human body—and discusses his text and the related section in Van Hoogstraten.

Van de Wetering begins by questioning the interpretation of the two principal modern commentators on these texts, Miedema and Weststijn, arguing that they have both misunderstood the texts’ function as handbooks for young painters by over-emphasising their theoretical nature. His detailed arguments are dense and occasionally meandering but never less than stimulating. Despite its format and lavish illustrations, this is not an easy read, but it is a rewarding one.

The great difficulty, of course, is that Rembrandt never stated his own approach to art, except in his famous use of the term “de meeste ende natureelste beweechgelickheijt” (here translated as “the most natural and expressive effect of movement”) in a letter to Constantijn Huygens in 1639. We cannot even be sure that he owned a copy of Van Mander. However, Van de Wetering is surely correct in his view that Van Mander’s book contains a world of ideas about painting that Rembrandt would have been aware of, even if he did not share those ideas himself. Van Hoogstraten was a pupil of Rembrandt, some of whose opinions he includes in the Inleyding. The degree to which his text represents—or reacts against—Rembrandt’s views has long been discussed, and here Van de Wetering adds his weighty voice to this continuing discussion.

Van de Wetering draws the strands of his argument together in chapter three. He sums up that Rembrandt did have a theory of art but what he has presented in this book is a sketch and needs to be developed further. He acknowledges that a key difficulty is one of definition: “theory of art” suggests classicist academic theories of art. Rembrandt, by contrast, had a number of principles and methods, often evolving during his career, all of which were subservient to his essential naturalism. Van de Wetering also includes three valuable appendices: a consideration of the function and meaning of Rembrandt’s self-portraits (which is a shortened version of his essay on the subject in Volume 4 of the Corpus); a summary of the Painter at Work; and a chronology of Rembrandt’s life, with discussion of works illustrated in this book. Rembrandt: the Painter Thinking is a product of a lifetime of study of Rembrandt, full of wise insights and with a freshness of approach that has long characterised Van de Wetering’s work on the artist.

• Christopher Brown is professor of Netherlandish art at the University of Oxford. He was the director of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from 1998 to 2014 and the curator of the Dutch and Flemish paintings at the National Gallery, London, from 1971 to 1998. He is currently preparing an exhibition, Young Rembrandt, for the Ashmolean and the Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, and is working on a new edition of Van Dyck’s Italian sketchbook

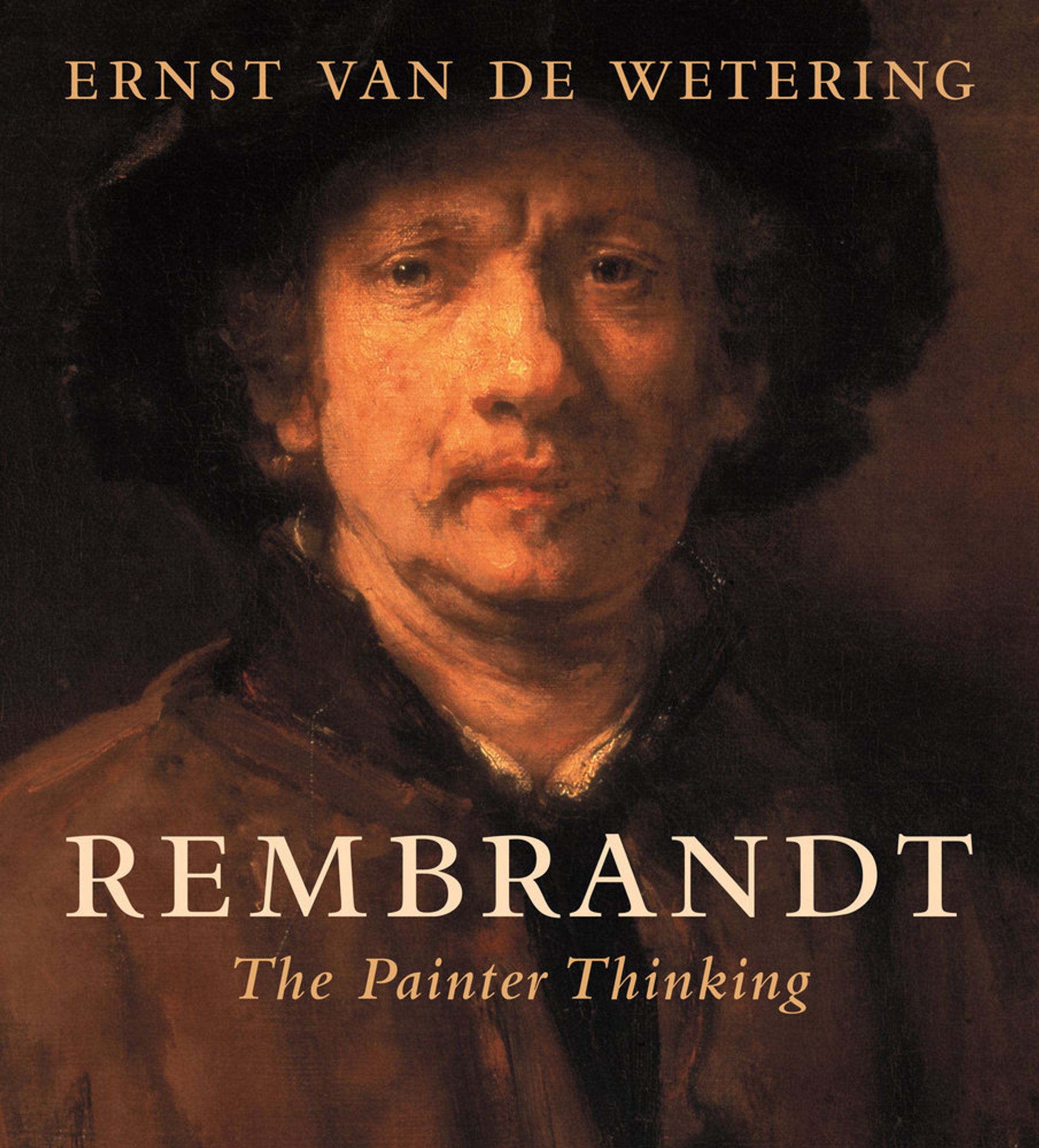

Rembrandt: the Painter Thinking

Ernst van de Wetering

Amsterdam University Press, 336pp, £64, €89 (hb), £34.95, €44.95 (pb)