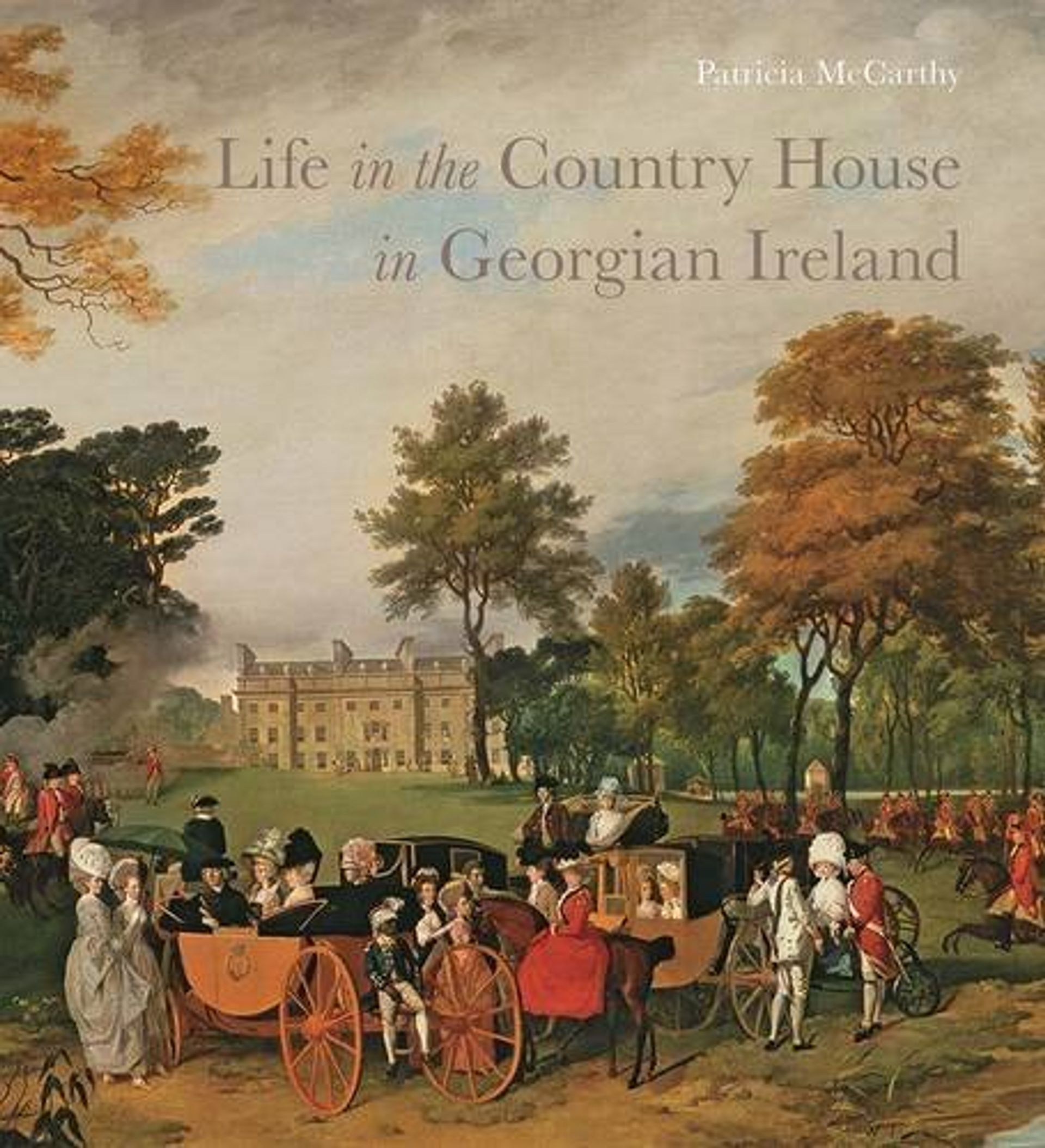

Irish country houses are the subject of this richly illustrated and scholarly book, Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland, by Patricia McCarthy, who examines not just the large houses built by the Anglo-Irish elite between the late 17th and early 19th centuries, but also the distinctive way they were lived in. Often larger than their English counterparts, Irish country houses were regularly criticised by English visitors as remote, uncomfortable and old-fashioned. However, in his Two Tours in Ireland, in the Years 1792 and 1792, George Hardinge complimented the country houses he saw on his travels: “I see as much taste and as much neatness without or within to the full as in England accompanied with more beauty of exterior for they are all of them white and grey-slated at top seldom irregular and hardly ever ill situated.” Frances Power Cobbe, writing in 1894, contrasted the appearance of Newbridge, Co. Dublin, her family home, with that of a neighbouring house, Turvey, the seat of Lord Trimleston, in almost anthropomorphic terms. Newbridge “is bright and smiling and yet dignified; bosomed among its old trees and with the green wide-spreading park opened out before the noble granite perron of the hall door … it has as open and honest a countenance as its neighbour has the reverse.” Turvey, “is really a wicked-looking house with half-moon windows which suggest leering eyes.”

McCarthy explores the various components of Irish country houses in her chapters, starting from the gate lodges that announce the house, and concluding with the “barracks” for servants in the garrets. Francis Goodwin, the architect of Lissadell, cautioned against making entrance halls too impressive, unless “they may be rendered too forcible and too favourable, and so occasion comparative disappointment in what follows”—advice he didn’t follow in the spectacular Greek Revival house he created overlooking Sligo Bay. Jonah Barrington described the hall at Cullenaghmore, Co. Laois, as “decked (as was customary) with fishing rods, fire arms, stag’s horns, foxes’ brushes, powder flasks, shot pouches, nets and dog collars; here and there relieved by the extended skin of a kite or king-fisher, nailed up in the vanity of their destroyers”. At Mellifont Abbey, Co. Louth, 12 medieval statues of the Apostles, removed from the venerable Cistercian abbey on the site, were displayed, kitted out with red uniforms and muskets. The Smythe family sometimes dined in their hall at Barbavilla, Co. Westmeath, waited on by domestics who emerged from a trapdoor in the floor.

Many houses had extremely showy interiors. The Earl of Clonmel had a drawing room completely furnished in blue damask, with silver furniture, at his house, Neptune, at Blackrock, Co. Dublin, in 1789, while at nearby Carton, Thomas Creevey stayed in the Chinese Bedroom in 1828, “French to the backbone in its furniture, gilt on the roof, gilded looking glasses in all directions, fancy landscapes and figures in panels”. Ardfert Abbey, Co. Kerry, may have been “a dismal place”, according to Lady Carlow, who visited in 1785, but Lady Glandore could at least escape to her delightful dressing room, “hung with white paper, to which she has made a border of pink silk, with white and gold flowers stuck upon it”. Some houses even boasted sophisticated bathing arrangements; in the 1820s, Lord Robert Tottenham, Bishop of Clogher, who suffered from a painful skin disease, bathed in red wine on the advice of his doctors—which was afterwards bottled and sold by his enterprising valet to the local villagers.

Everyone seemed to comment on the swarms of servants in Irish country houses. “We keep many of them in our houses, as we do our plate on our sideboards, more for show than use, and rather to let people see that we have them than we have any occasion for them,” wrote Samuel Madden in 1738. Lord Abercorn’s journeys between his Irish seat, Baronscourt, Co. Tyrone, and the family townhouse in London took a month, attended by 33 people in a cavalcade of four carriages and ten outriders.

• Tim Knox is the director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. He studied history of art at the Courtauld Institute of Art and was assistant curator of the RIBA Drawings Collection from 1989 to 1995. He was the National Trust’s architectural historian, becoming its head curator in 2002, and was the director of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London between 2005 and 2013. He is co-patron of the Mausolea & Monuments Trust, which he helped found, and is a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge

Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland

Patricia McCarthy

Yale University Press in association with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 272pp, £45, $75 (hb)