Sculpture and Nakedness: Corporeality and Eroticism in the Works of Ivan Mestrovic

Dalibor Prancevic, Barbara Vujanovic and Zorana Juric Sabic

Ivan Mestrovic Museums, 172pp, £12 (pb)

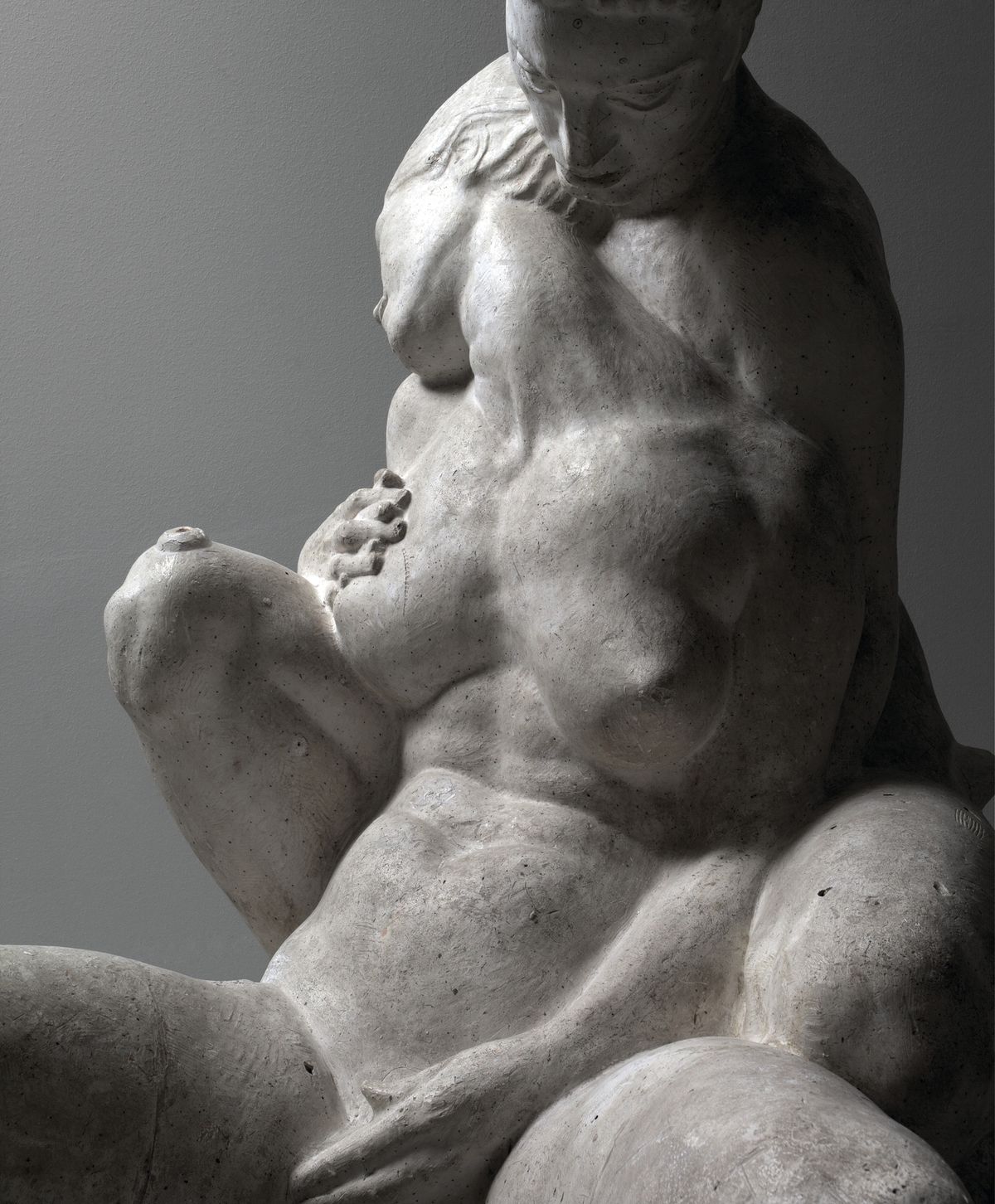

At the end of last year, while the spotlight was on Rodin with the reopening of the Musée Rodin in Paris, in Zagreb curators were adding the finishing touches to a major exhibition of work by a man Rodin himself once described as “the greatest phenomenon among artists of today”—Ivan Mestrovic (1883–1962). The admiration, which was mutual, was understandable: the two artists had a lot in common, not least an obsession with the naked human body in all its power, erotic glory, spirituality and frailty.

It was this aspect of Mestrovic output that was explored in the Zagreb show. Sculpture and Nakedness, its dual-language (English and Croatian) catalogue, is a significant contribution to the rather thin body of literature in English on one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. This is not a beginner’s guide to Mestrovic and it helps to know something about his life, as the essays reveal how closely rooted the works are in his biography.

The sculptor certainly lived in interesting times: his career spanned a turbulent period in Balkan history, and his travels brought him into contact with a succession of revolutionary developments in European art. After early training as a stonecutter in Croatia he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna when he was just 17, befriending and exhibiting with the Secessionist artists Klimt and Schiele. His early sculptures were formed in the crucible of a Vienna permeated with Freudian theories and they reveal an ambivalence about sexuality and the human body, as well as a fascination with its decay.

Mestrovic’s move to Paris in 1908 also left its mark. It was there that he struck up a friendship with Rodin, which continued until the older artist’s death in 1917. Quite apart from the thematic similarities between their works, the two men shared a broadly Impressionistic approach to modelling—the boldness of Mestrovic’s massive undulating forms can be appreciated in the book’s close-up photographic details. A subsequent four-year spell in Rome brought the artist face-to-face with Michelangelo and antiquity, a legacy that can be seen in the classicising sculptures of the 1920s and 30s. But the narrative stops short of his self-imposed exile from Croatia and emigration to the US after the Second World War. While Mestrovic created several public monuments, the works reproduced here are private in flavour.

• Caroline Bugler is a writer and editor specialising in art, and was formerly the editor of Art Quarterly

Building a Crossing Tower: a Design for Rouen Cathedral of 1516

Costanza Beltrami

Paul Holberton Publishing, 136pp (pb)

Medieval drawings made for the execution of Gothic churches are fashionable as never before. Their embodiment of geometry as a fundamental part of the design process—not “sacred” or “Platonic” geometry, but practical generation of form by means of geometry—is presently the object of intense specialised study.

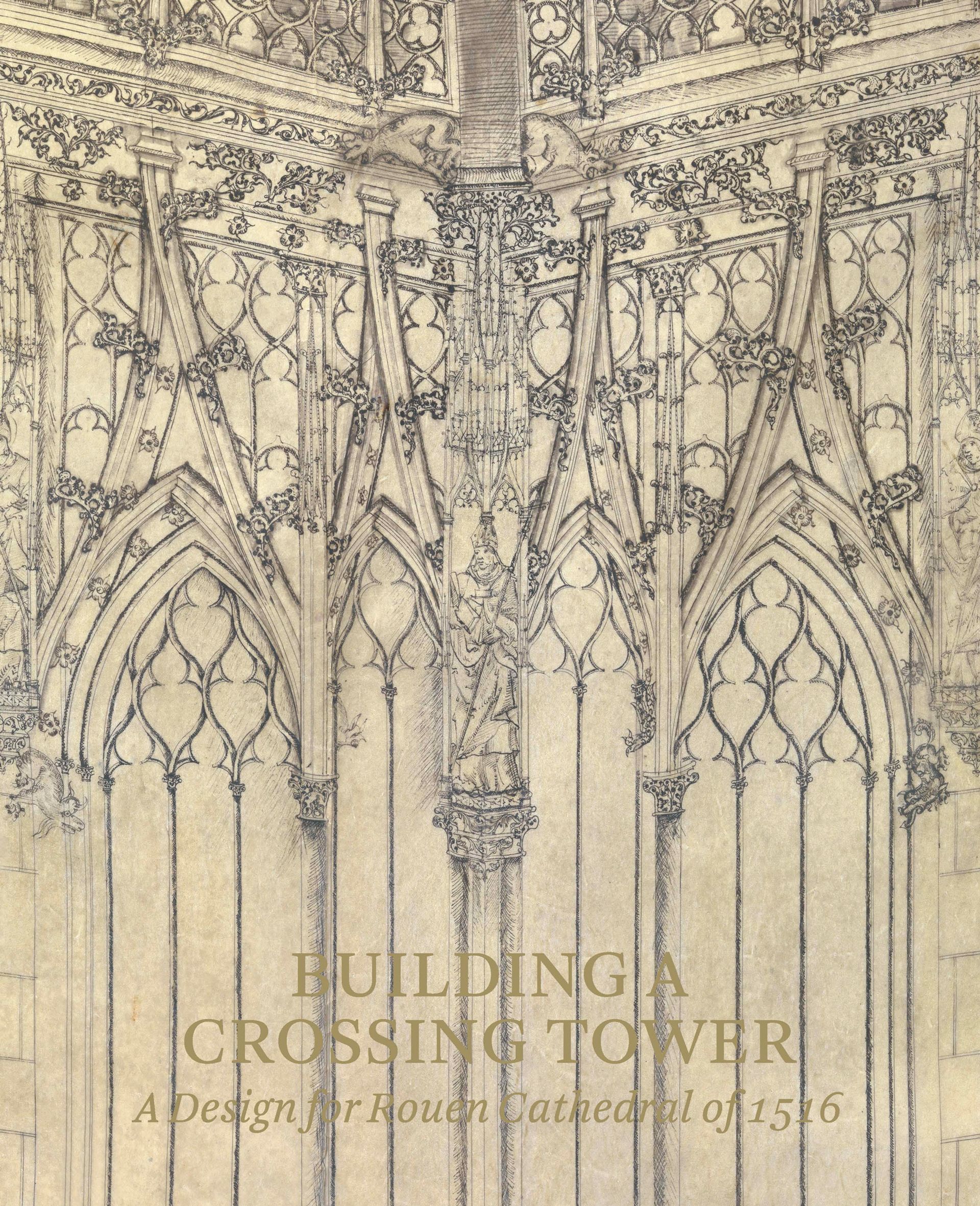

Such drawings survive first from the mid-13th century, though they were probably used earlier. What changed in the course of the Middle Ages was their technical excellence, their expert working-through of scaled detail as well as their virtuosic overall composition. Between the 13th and 16th centuries the majority of such drawings, on parchment in large scale, usually show the expensive optional additions to any great church, namely portals and towers. By nature they are show pieces. Most—about 600 by one estimate—survive from what is now Germany and also from Vienna in particular, with few from England and France, for reasons which are obscure. It has never been clear how such large drawings were intended to be used, but the likelihood is that they were intended to inform and impress building committees and donors. They had to convey the general effect of a projected building despite its great cost, and so had to have persuasive power. Most such drawings are carefully worked-out, planar elevation drawings. The excitement of the example published in this book derives in part from its different character. The hitherto-unknown drawing, on parchment sheets 3.5m tall, first appeared in London, having left a French private collection in 2014, but its origins, as the author shows in this beautifully published short study, are indeed in France, specifically the Rouen area, in the early 16th century. The book attributes it to Roulland le Roux, master mason of Rouen cathedral around 1500-20. The drawing shows a spiky, ornate, four-tier tower with statuary and tracery, topped by a tall, thin spire reminiscent of the cast-iron spire eventually raised over Rouen cathedral’s central tower in the 19th century. But was it a design for the cathedral? The task of the author is to solve this puzzle and set this very unusual drawing in context, and also to account for its one really striking feature—the fact that it is presented obliquely, and so perspectivally. That this form of presentation—anticipating the modern artist’s impression—itself had rhetorical purpose is a possibility raised in this effective and well-documented publication.

• Paul Binski is professor of the history of Medieval art at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College

The Burdens of Wealth: Paul Getty and His Museum

Burton B. Fredericksen

Archway Publishing, 470pp, $28.99 (pb)

On 28 January 2016, at Sotheby’s New York, the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired Orazio Gentileschi’s painting, Danaë (around 1621), for a little more than $30m. That dazzling event calls to mind the night in early June 1976—described so vividly in Burton Fredericksen’s riveting history—when the Getty Museum learned that a vast shower of gold was to pour on them in the form of the bulk of the just-deceased Getty’s massive fortune. Only the tycoon’s accountant and certain of the museum’s trustees and family members knew of Getty’s intention.

Realising that the industrialist’s years were numbered, the institution’s three curators, among them Fredericksen, had bought what they could, all the time imagining that the funds for art purchases would evaporate upon Getty’s demise. Then overnight the playing field changed completely. The rest—as the world knows—is history.

Fredericksen’s 460-page account, which runs from 1953 to 2013, is brilliant, diverting and hugely informative. His ability to absorb and dispense vast amounts of accurate and relevant data is what one would expect from the museum’s former senior research curator and director of the provenance index, a branch of the Getty Research Institute that was founded in around 1984.

According to Fredericksen, the expanded museum’s early years resembled a “troubled adolescence”. Its darkest moments were under the eight-year administration of Barry Munitz, the turbulent second CEO and president of the Getty Trust (the umbrella organisation for all Getty- funded charitable institutions).

Yet Fredericksen’s chronicle of the museum’s purchases (in Western art, at least) is largely a happy and well-considered one. His many character sketches are shrewd and, it would seem, fair. The final chapter, Righting the Ship, sounds a hopeful note. Every page of Fredericksen’s book, in sum, amounts to first-rate reading.

• Eliot W. Rowlands, a freelance art historian and specialist in early Renaissance Italian paintings, lives in New York

Kunst im NS-Staat: Ideologie, Ästhetik, Protagonisten [Art in the National Socialist State: Ideology, Aesthetics, Protagonists]

Wolfgang Benz, Peter Eckel and Andreas Nachama, eds

Metropol Verlag, 472pp, €24.90 (hb);

in German only

Since Joseph Wulf’s comprehensive survey of the cultural politics of the Nazis—a good half-century ago in his five-volume series on the arts in the Third Reich—we have seen a flood of publications covering all aspects of this subject.

In this move to specialisation, though, the wider context of Nazi policy was to some extent overlooked. In the first half of 2015, therefore, the Topography of Terror documentation centre on the SS and the Gestapo in central Berlin held a series of events focusing on the arts supported by the National Socialist state. Now these lectures have been gathered together in a volume that, for all its 472 pages, is still relatively compact and easy to handle.

For a long time, interest focused on the ostracised arts, while the official art was dismissed offhand as non-art. Today we can no longer simplify the situation to the same extent, as research has revealed a multitude of interconnections, interdependencies and continuities. This is most apparent in the spheres of architecture and film, but also in music, popular music especially. The fine arts notably made themselves serviceable and 1933 was by no means the radical dividing line presented by the Nazis—who framed it as a “national Revolution”—and by artists, many of whom were only outlawed at a later date. All of this is addressed in the 28 chapters of this anthology whose authors—all eminent figures—offer an exemplary summary of the latest state of knowledge in their respective fields.

• Bernhard Schulz is the art critic of Der Tagesspiegel, Berlin