From the outside, not much has changed. After a three-year, $69m renovation, the East Building of the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, looks about the same as it did when it first opened in June 1978. The I.M. Pei-designed building, dedicated to the museum’s collection of Modern art, still comprises two triangular blocks of stone, with the architect’s signature glass pyramids at its front entrance.

Step inside and the differences become clear. The gallery, which reopens to the public on 30 September, has managed to carve out more than 12,250 sq. ft of additional exhibition space without expanding its physical footprint. The changes have inspired a comprehensive reinstallation of the collection that will transform the way more than four million annual visitors understand the story told by DC’s premier art museum.

Stairway to new space The ambitious project grew from practical reasons. In 1999, the museum began executing a federally funded facilities plan to upgrade ventilation systems and fire safety measures across the institution. In the West Building, dating from 1941, galleries could be isolated, so it was possible to complete the upgrades in stages. In the East Building, which is much more open, this was not the case. “We knew we had to close it and de-install all the art,” says Susan Wertheim, the museum’s in-house architect.

The next big challenge was to build a new staircase to connect each floor of the building. Before the renovation, visitors could either use an elevator or navigate a maze of galleries to get from the bottom of the building to the top. When the museum turned to Pei for advice, he suggested that his former colleague Perry Chin develop the concept for the renovation. (Hartman-Cox Architects executed the design.)

In the course of his research, Chin learned that the NGA’s director, Earl A. Powell III, had expressed interest in adding gallery space. Chin suggested they make a section of the building’s roof into an outdoor sculpture terrace, adding 6,105 sq. ft. Another solution came to him in conversation with Pei. Chin proposed opening up two of the museum’s closed-off towers and inserting an extra floor at the top of each to supply an additional 6,155 sq. ft of indoor exhibition space.

In the end, the decision to move forward was more about quality than quantity. “We found this beautiful space and, as architects, we appreciate these things,” Chin says of these previously unused areas. “It’s like candy.”

Federal funding ($39m) covered only the master facilities renovation, not the new exhibition space, so five Washington philanthropists—Victoria Sant, then the gallery’s president, and her husband Roger, who sits on the trustees council; the trustee Mitchell Rales and his wife Emily; and the financier David Rubenstein—stepped in to provide the necessary $30m.

A clearer history of art While the surgical renovation was under way, Harry Cooper, the NGA’s head of Modern art, had another task: to determine how to reinstall the collection. First, he wanted to establish a clear historical narrative. “You have to see art in development over time, with movements responding to one another,” he says.

Previously, the presentation had been more disjointed, with contemporary art at the lowest level and other 20th-century work on the top floor. In the new installation, the galleries are arranged largely chronologically, beginning with early Modernist works by artists such as Picasso and Modigliani near the front entrance, in what was formerly a gallery containing small French paintings. Upstairs, galleries continue the story though Fauvism, Cubism and onward.

But Cooper is also aware that audiences have their own expectations. “An educator was telling me the other day that foreign visitors want to see American art [because] they can see European art all around the world,” he says. At the NGA, they will have plenty of opportunities. The three light-filled tower galleries are currently devoted to Alexander Calder, Barbara Kruger, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. A presentation of work by Theaster Gates is planned for 2017.

The museum has been criticised for its lacklustre record in showing female artists and artists of colour. (According to the Washington City Paper, the NGA organised just one exhibition by a living female artist and one by a living African-American artist before the East Building’s reopening.) Cooper stresses that the reinstallation is only one perspective. “It’s not the history—it’s a history,” he says.

Whatever its guiding principles, the display is richer than before: with the extra gallery space, 525 works are now on show, compared with 350 in the original hang. They have many different ideas to get across, but Cooper aims to communicate artists’ common concerns.

“I hope people get a sense of Modern art as a single, albeit rather wide and diverse, tradition, that evolves through a century and more,” he says. The other goal is to help visitors expand their tastes. “Hopefully, people come out with some new top-ten lists.”

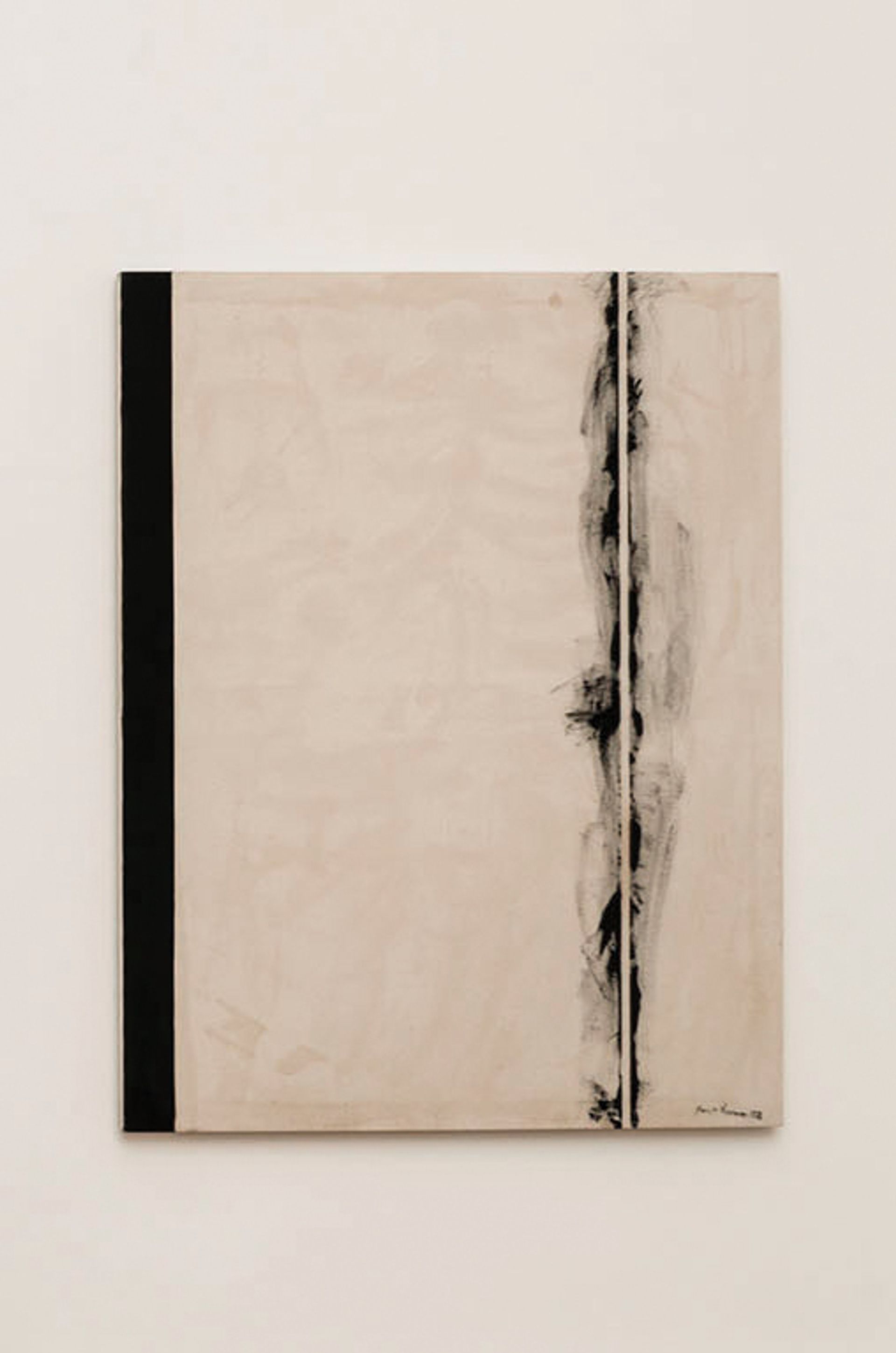

In the towers Mark Rothko is a particular point of pride at the NGA: in 1985 and 1986, the artist’s foundation donated 295 of his paintings and works on paper to the museum, along with more than 650 sketches. Eleven of his best paintings are presented in the new north-east tower gallery, along with Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross series (1958-66). The combination creates a temple-like atmosphere.

The north-west gallery contains the largest solo presentation of work by Alexander Calder in any US museum. A selection of more than 20 sculptures lent by the artist’s foundation includes Vertical Constellation with Bomb (1943). Calder created the work while living on a farm in Connecticut during the Second World War.

The original tower gallery reopens with a show of work by the Los Angeles-based artist Barbara Kruger (until 22 January 2017). It includes 15 of her “profile” pictures, which are overlaid with cryptic text. The show covers Kruger’s work from the early 1980s to the present and includes wallpaper she designed for the space.

The dealer who helped artists think big The dealer and patron Virginia Dwan is at the centre of Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959-71, the first temporary exhibition in the renovated East Building (until 29 January 2017). Through 100 works, the show examines Dwan’s role in a moment of profound art historical transition, as artists became more interested in working outside the white cube than within it (as with Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, built in the Great Salt Lake in Utah in 1970). Dwan has promised 250 works from her collection to the NGA.