Institutions, like Hemingway characters, fail two ways: gradually, then suddenly. In early 2014, the beleaguered Corcoran Gallery and School of Art in Washington, DC, having exhausted every option for saving itself, agreed to a takeover by George Washington University and the National Gallery of Art (NGA). The university absorbed the school and $48m in cash and endowment as well as the Corcoran’s Beaux-Arts building across the street from the White House. The NGA agreed to run the Corcoran’s former art galleries and take over its collection. Curators at the NGA got first pick of the 17,000 works and will help to distribute the rest, with a preference given to local institutions.

While the overhaul of the school has been fraught with public criticism, the NGA has been deciding the collection’s fate almost entirely out of sight. More than 8,300 objects have been accessioned, some of which are already on show. The new additions—43 Modern and contemporary works in the newly renovated East Building and 166 in the neoclassical West Building—tweak the existing narrative and fill longstanding gaps in the country’s official history of art.

The Corcoran Gallery, founded in 1869 by the US banker and collector William Corcoran, was the first art museum in Washington, DC. Between the art school, founded in 1890, and the Corcoran Biennial, begun in 1907, the museum consistently supported and collected the work of living US artists before mounting deficits forced it to close two years ago.

Christmas morning feeling After the takeover was finalised in June 2014, the NGA’s first task was to produce an inventory of the gallery’s holdings. It was more challenging than anticipated. The Corcoran had an archive and three collection management systems but none was definitive. Many of the lists were not illustrated, so thumbing through works “was a little bit like opening up presents on Christmas morning”, says the NGA’s photography curator Sarah Greenough.

The Corcoran’s works on paper were stored in “one small, jammed space” and it took two teams of curators six months in the storeroom “just to make our first pass”, she says. They sorted through early and late prints of the same images; student works; and even exhibition prints that had been accessioned, or at least kept, after shows had closed.

So far, the NGA has taken 5,032 prints, drawings and watercolours and 2,285 photographs from the Corcoran. (Trustees made the final round of acquisitions as we went to press.) For a department that acquired an average of 326 photographs per year between 2010 and 2014, the impact has been substantial.

The process was simpler for other departments. Curators of Dutch, Italian and British paintings took in fewer than three-dozen works, including a gilded altarpiece by Andrea Vanni. Modern art curators acquired 227 works out of 1,000. The American paintings department accessioned 249 works, many of which were equal, if not superior to, the NGA’s existing holdings. To manage the accessions and preserve institutional knowledge about the collection, the NGA also brought along five former Corcoran curators: one full time and four as consultants.

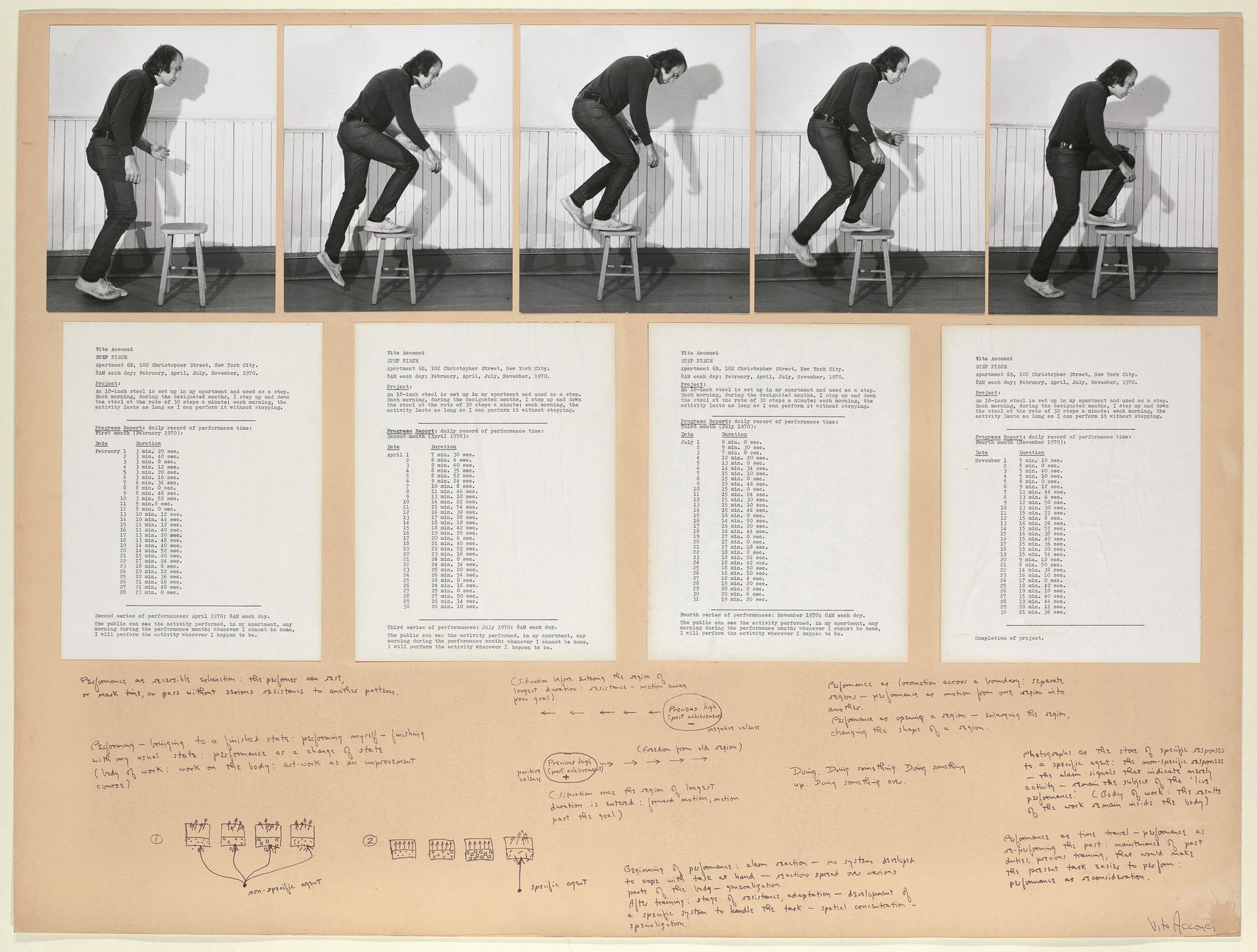

Filling the gaps The first exhibition of the merged collections (Intersections, until 2 January 2017) offers a taste of how the Corcoran will bring new relevance to previously overlooked works at the NGA. Curators paired Eadweard Muybridge’s No 180 (1887), one of 700 works by the artist acquired from the Corcoran, with Vito Acconci’s photo collage Step Piece (1970). In his conceptual work, never before shown by the museum, Acconci essentially re-performs Muybridge’s time-lapse study, an unexpected echo across more than 80 years. Upcoming shows of work by Gordon Parks, due to open next year, and Sally Mann, in 2018, also draw heavily on Corcoran acquisitions.

“We can tell a whole new story here,” says the curator Nancy Kay Anderson, who used the Corcoran’s American paintings collection to deepen the narrative of the Civil War and flesh out a gallery of domestic portrayals of women. “We didn’t have this type of painting: Boston School, women, turn of the century,” she says. “We didn’t exist as a museum when the Corcoran was buying these paintings from the artists.”

Harry Cooper, the museum’s head of Modern art, also used the collection to fill gaps, particularly in the NGA’s holdings of work by local artists, women and artists of colour. But he knew that other institutions might benefit more from some of the Corcoran’s treasures. He declined to take a drape painting by Sam Gilliam because the museum already had a similar example. “I know some of my colleagues were thinking, ‘If it’s good enough, take it,’” he says. “But I was also thinking, ‘Will we show it?’”

Similar restraint abides in the West Building. “When we have 42 Gilbert Stuarts, the chances that we’ll show the Gilbert Stuarts from the Corcoran are remote, so why not have them go to the [National] Portrait Gallery?” Anderson says. (It is not clear how many they declined, but the NGA did take four Gilbert Stuarts, including two portraits of George Washington, bringing their collection of Stuart Washingtons to six.)

Once the final accessions are complete, the NGA will deliver to the Corcoran’s remaining trustees the inventory of works for distribution. Curators say colleagues from local museums and universities have been making requests for months. If necessary, the Corcoran will also invite government buildings, libraries and schools to take what is left. Nothing is expected to be sold.

Even after the art is taken care of, the Corcoran will not dissolve. The NGA is planning to launch a satellite contemporary art programme in the Corcoran building, although a time frame has not been confirmed. According to an order from the DC Superior Court, which approved the takeover in 2014, the Corcoran will retain its federal charter “to operate as a non-profit entity, dedicated to ‘encouraging American genius’”.

Old friends, new home