“What is an art fair actually?” asks Michael Elmgreen, one half of the Berlin-based duo Elmgreen and Dragset. “We love to go, and we love to complain about it.” Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, the duo’s other half, explored this art world institution at their fake art fair solo show, The Well Fair, at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing earlier this year. They are continuing this inquest with a one-day pop-up event at the Grand Palais in Paris on 24 September, Galerie Perrotin. The installation is an exact preview of Perrotin’s booth at the Fiac art fair, opening on 19 October—in the same spot in the Grand Palais Nave, with the same dimensions, the same presentation of works, the same furniture, all curated by the artists.

The aim is to give an entirely new perspective on an art fair by seeing just one small booth in the otherwise empty space of the massive, light-filled Nave of the Grand Palais. “It’s standing there alone, it’s quite vulnerable,” Elmgreen says of the solo booth, calling it “fantastic” to see just one curated presentation of works, rather than the saturated mix crying “buy me buy me buy me”. As a unique space, before it is “enveloped by all the other galleries”, the booth “is actually quite charming”, he says. The works on show include pieces by Elmgreen and Dragset, who are represented by Perrotin, and other gallery artists such as Jean-Michel Othoniel, Sophie Calle and Gregor Hildebrandt, all in a black and white palette (as were the works in The Well Fair). “It’s almost like the starting point of the whole Fiac is coming from that tiny little lonely booth,” Elmgreen says.

The pair also has a solo show, Elmgreen and Dragset: Changing Subjects, coming up at the Flag Art Foundation in New York in October (1 October-17 December), with works from 1998 to the present on two levels. One of the two new works on show is a site-specific installation on the foundation’s terrace, human-sized lifeguard called Watching (2016) overlooking the Hudson River, made of polished stainless steel to reflect the Chelsea skyline. The other new work, Human Scale (2016), is made of stainless steel rulers attached to a wall that give the dimensions of the body parts of an anonymous adult. “The body has completely boiled down to be just these numerical values spread out on the wall,” Elmgreen says. This forms an interesting contrast to the hyper-real sculptural representations of the human body in some of the other works in the exhibition, such as The Experiment (2011), which shows a young boy trying on his mother’s lipstick and high heels in front of a mirror.

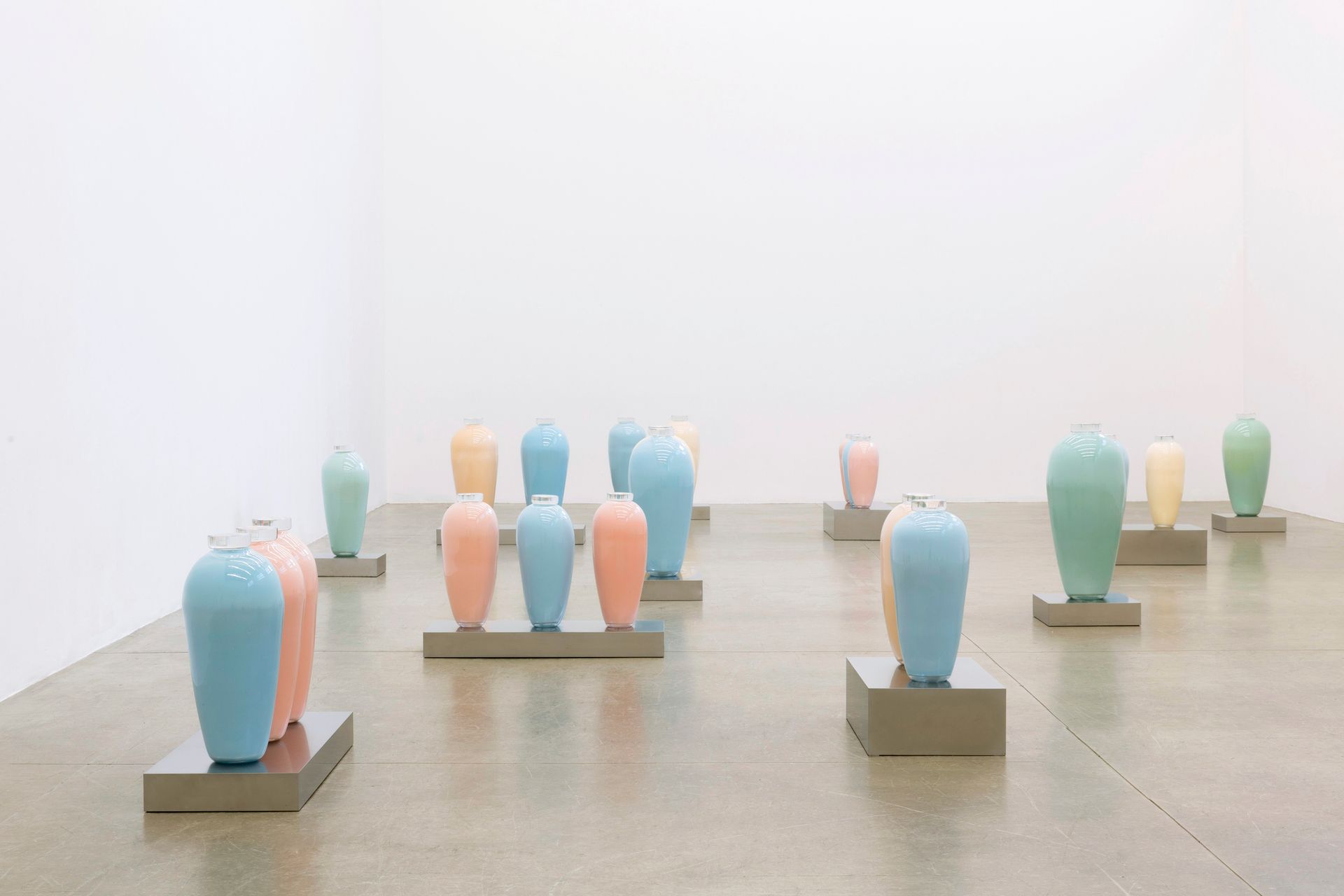

The upper-level gallery space will be entirely dedicated to one work, Side Effects (2015), hand-blown, clear glass vases that contain the pastel powdered food colouring pigments that are used in the latest wave of HIV medication. The colours look “a bit like candy” Elmgreen says, and have a calm visual appearance, “camouflaging” the toxic side effects that such medications have, even though “we are fortunate that we actually are in a position where we can survive HIV”. The work also addresses the lasting stigma of HIV/Aids, “even within the gay community itself”. New York is an appropriate place to show the work because of the city’s history with the Aids crisis in the 1980s and more recent activism, Elmgreen says—and “of course” it is also timely with the approaching US presidential election.