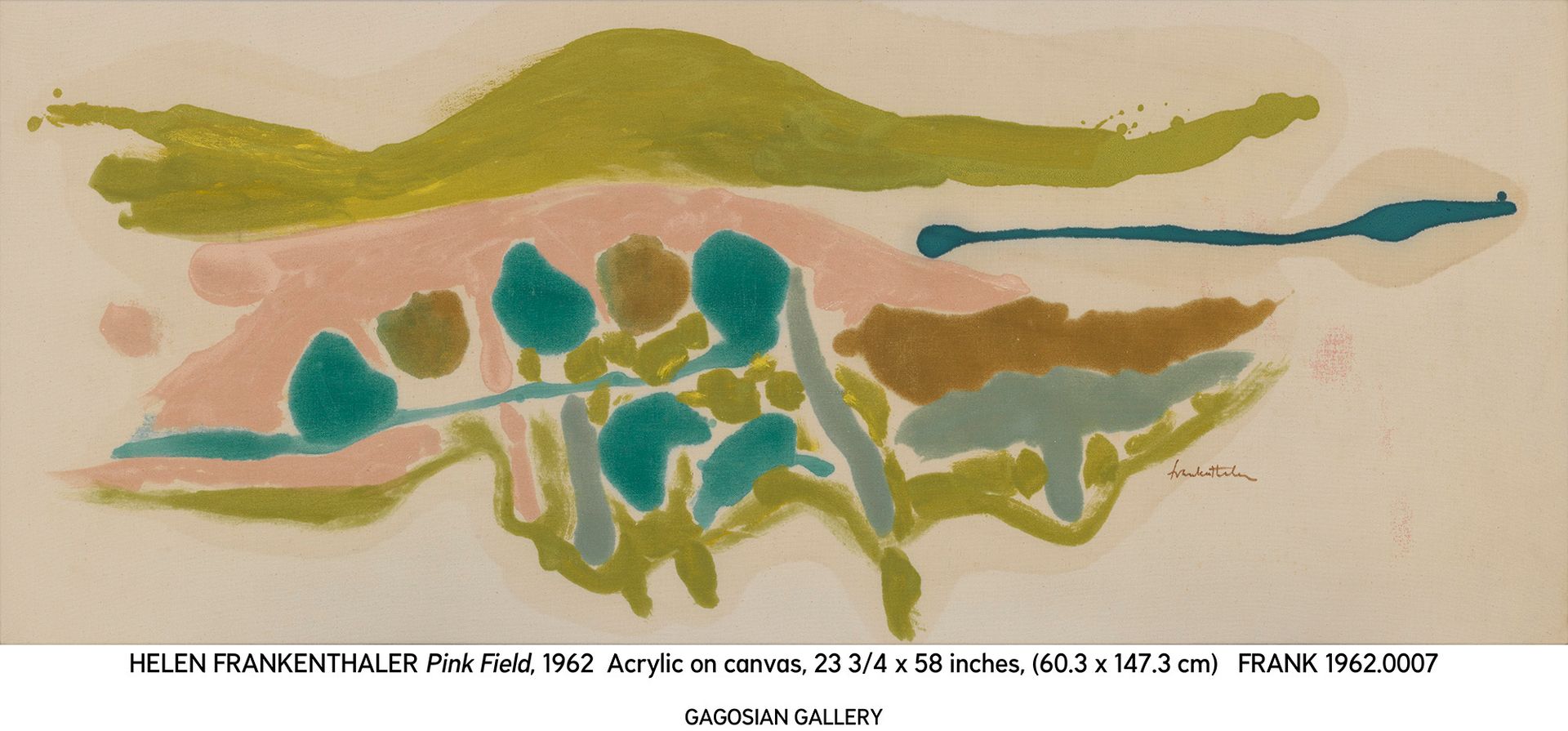

History has a way of tethering artists to dates. In this way, the late Helen Frankenthaler is tied to 1952, when she invented the “soak-stain” method. Pouring paint thinned by turpentine directly onto raw canvas, she created pools of luminous colour in works such as Mountains and Sea (1952), which inspired the Color Field movement. Less is known of her later work. But, a new exhibition aims “to show that she continued to be an inventive artist” through the six-decade career that followed, says the curator John Elderfield, who has organised Line into Color, Color into Line: Helen Frankenthaler, Paintings, 1962-87, opening at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills this week (16 September-29 October).

With 18 paintings, the exhibition focuses on the “relationship of drawing to painting and how the two elements relate throughout,” says Elderfield, who was chief curator of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) until his retirement in 2008. Frankenthaler’s work in the 1960s is more about contours than independent drawing, he adds. Then we see traditional elements such as “filaments of line” reappear in her canvases from the 1970s through the 1980s, as the artist experimented with different kinds of mark making.

Frankenthaler kept a lot of her own work for herself, and all the paintings in the show come from her estate (which is now largely managed by the foundation she established and endowed before her death in 2011). “There is so much in the foundation that it seemed a really good idea to get out these works that hadn’t been shown a great deal,” Elderfield says.

His familiarity with Frankenthaler dates back to the first major show he curated at MoMA, Wild Beasts: Fauvism and Its Affinities in 1976. “Helen had seen the exhibition and left me a note saying she thought it was wonderful. I thought that was great—it’s nice to get fan mail,” he says, laughing. The next day, the phone rang and it was Frankenthaler. “She said: ‘I’ve been reading your catalogue, which I really love. Maybe you’d like to write a book about me?’ I had to say I just couldn’t do it, I had too much to do.” He went on to write the authoritative text on the artist, published in 1989. “Eventually, I weakened,” he says.

This is Elderfield’s third Frankenthaler show for Gagosian, for whom he has been consulting since his retirement, among other projects. (He is also curator emeritus at MoMA, the Adler Distinguished Curator of European Art and Lecturer at Princeton and is organising an exhibition of Cézanne portraits that will open at the Musée d’Orsay next year before travelling to London’s National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.)

Exhibition planning at a gallery takes place at a different clip than institutions, Elderfield says. “It’s been really fun for me to realise how quickly these things can be done, I actually think museums could learn from it.” Museums tend to require a minimum of two years to produce exhibitions, “which is crazy”, unless a show requires extensive research or difficult loans, he says. “I’m not advocating for things being done so quickly that they’re sloppy, but one finds that even museum shows that have taken a long time can still be sloppy.”

For Elderfield, the Gagosian exhibition is an opportunity to show works he has long admired but seen little since they were first created. “The late 1980s pictures were being made at the time I was working on the book. It will be fantastic to see them on the gallery walls,” he says. “Some of these paintings are absolutely extraordinary.”